Not all podcasts are fun (for either the guests or the viewers) but in my experience all podcasts hosted by Bob Murphy are fun for all involved. You can see the latest here or on YouTube:

Archive for the 'Technology' Category

Edit: Here is a new and improved version of the post below. I am leaving the original up for historical reasons, but I recommend following the link instead of reading this post.

*****************

Yesterday, I announced on this blog that ChatGPT had failed my economics exam. (All of the questions on this exam are taken from recent final exams in my sophomore-level course at the University of Rochester.) Multiple commenters suggested that perhaps the problem was that I was using an old version of ChatGPT.

I therefore attempted to upgrade to the state-of-the-art GPT-4, but upgrades are temporarily unavailable. Fortunately, our commenter John Faben, who has an existing subscription, offered to submit the exam for me.

The result: Whereas the older ChatGPT scored a flat zero (out of a possible 90), GPT-4 scored four points (out of the same possible 90). [I scored the 9 questions at 10 points each.] I think my students can stop worrying that their hard-won skills and knowledge will be outstripped by an AI program anytime soon.

(One minor note: On the actual exams, I tend to specify demand and supply curves by drawing pictures of them. I wasn’t sure how good the AI would be at reading those pictures, so I translated them into equations for the AI’s benefit. This seems to have had no deleterious effect. The AI had no problem reading the equations; all of its errors are due to fundamental misunderstandings of basic concepts.)

Herewith the exam questions, GPT-4’s answers (in typewriter font) and the scoring (in red):

I am pleased (I think) to announce that I have just submitted to ChatGPT an exam, consisting entirely of questions taken from recent final exams in my sophomore-level intermediate economics class, and it has earned a score of zero. Not only did it earn a score of zero, but several of its answers would have merited negative scores if I were allowed to give them. The answers are in every case egregiously wrong, showing absolutely zero understanding of the basics.

I am frankly a little surprised; I had expected it to get at least a few things right.

Edited to add: If you are looking for the details, look here.

Okay, so according to the news, the FBI has recovered the bulk of the Bitcoins paid as ransomware by the Colonial Pipeline Company, by acquiring the private key to the address where those Bitcoins were stored.

No news source I’ve seen has offered anything approaching an answer to the question: How did the FBI get ahold of that private key? Did the criminal masterminds behind the ransomware attack just leave it, unencrypted, on a hard drive or a piece of paper in a place where the FBI was likely to look?

At first I thought the most likely answer was that the FBI must have traded something for that key — say some sort of immunity (either from prosecution or, maybe, from something like a beating). But on second thought, it occurs to me that maybe hiding a private key from the FBI is trickier than it sounds.

I know plenty of good ways to hide private keys from thieves. You can write your key on a piece of paper (or better yet, etch it in metal) and store it in a safe deposit box. Or, for extra security (say if you’re worried about bank employees accessing those boxes), put half of it in one safe deposit box and the other in another, at a different bank. Or, if you’re worried about one of those banks being reduced to rubble in an earthquake or a terrorist attack (in which case no criminal could get your key, but neither could you), you can break the key into three parts, store parts A and B at Bank One, parts B and C at Bank Two, and parts A and C at Bank Three. Any one bank can disappear and you can still recover your entire key.

That secures your keys and makes them safe from criminals, but it does not make them safe from the FBI, which has the power to issue subpoenas to all of your banks and recover the contents of your safe deposit boxes. So maybe hiding your keys from the FBI is harder than it appears.

So let me try again: After etching them on metal, store parts A and B at Location One, parts B and C at Location Two, and parts A and C at Location Three, where you expect to have access to all of these locations (and only really need access to two of them) but none is particularly tied to you — i.e. not your house, not your car, not your safe deposit box. Maybe underground locations in the woods, though that feels a little sketchy to me. And then of course you might want to keep some sort of written record of those locations, which the FBI can find when they search your house or safe deposit box, whereupon they might wonder what’s so interesting about those locations that you felt the need to keep track of them….

You might think the safest thing is to memorize your key (or a mnemonic English phrase from which the key can be derived) and leave no record of it anywhere except in your own brain. That’s fine until dementia starts to set in, or until you’re hit by a bus (in which case your heirs are out of luck, though you might or might not care about that). Or you can leave written clues to the mnemonic that only you will be able to decipher, like “Word 9: The secret nickname I had for the girl I had a crush on in third grade”. This is of course also subject to the dementia problem.

So. Suppose you’re a master criminal, storing your ill-gotten gains as Bitcoins, which you want easy access to at all times for yourself (and maybe your heirs), but you want to keep completely inaccessible from law enforcement agencies with unlimited subpoena power. What’s your plan?

Update: More recent news reports indicate that the coins were seized from a custodial account — based in the United States, no less. In other words, my sarcastic reference above to “criminal masterminds” was not nearly as sarcastic as it should have been. It’s not that these guys failed to think of a clever scheme for hiding their keys; it’s that they never even bothered to try. The more interesting question, then, is how does Bitcoin fall 10% on the “news” that if you let someone else hold your private keys, you can lose your Bitcoins. (“Not your keys, not your coins”, as the saying goes.) The best answer I have (not just for this event but for a lot of Bitcoin volatility in general) is that anything even slightly unsettling leads to a small drop in prices, whereupon heavily leveraged investors fail to meet their margin calls, which leads to big selloffs. But that’s not a full answer until someone fleshes out the part where more sophisticated investors fail to jump in and take advantage of this buying opportunity. So maybe the dip, despite the coincidental timing, had nothing to do with the seizure.

Technology marches on, and many of the flash videos I’ve posted here over the past fifteen years or so have become mostly unwatchable, because almost nobody uses flash players anymore. So I’ve just spent the better part of a day updating all of those videos to more modern formats. This means that if you have occasion to read old posts with videos in them, the videos will actually work now.

While I was at it, I updated this site’s video page, which you can get to by clicking on the menu at the top or by going directly here. This too had become unusable because of all the flash video. I updated the video formats and added several more items. Let me know if you have any special favorites you think I should add.

As my good deed for today, I’m posting a solution to a problem that I’m sure is plaguing others. I hope Google points them here.

I’ll say this much for brick-and-mortar booksellers: Not one of them ever sold me a book, then showed up at my house two years later, pulled the book off the shelf and started highlighting passages for me. I can’t say as much for Amazon, which has been selling me books for many years and has suddenly decided to highlight passages in all of them. Effectively, they’ve vandalized every book they’ve ever sold me.

Yes, I know about the checkbox in the settings for “Show Popular Highlights”. (This is in the Android Kindle App.) Yes, I have that box unchecked. I am not an idiot. Unchecking the box has no effect. Checking it and then unchecking it again has no effect. The highlights remain highlighted.

Here are some other things that don’t work: Clear the app cache. Reboot the phone. Express rage.

So I called Amazon customer service and had the good luck to hook up with Brandi G., who was fantastic. She instantly understood the problem, instantly understood everything I had tried to do to fix it, and, unlike what I’ve come to expect from customer service reps pretty much everywhere, she did not insist that I try all the same things again. Instead, she suggested that I uninstall the app completely and reinstall it, and she stayed with me on the phone to see how things would turn out. Presto! Problem solved. Yay Brandi.

Then an hour later, the popular highights came back.

So I uninstalled and re-installed about six more times (because that’s the kind of guy I am) and finally called Amazon again. This time I had the bad luck to hook up with Devan J., who kept me on the phone for 35 minutes, mostly in silence while he researched the problem. (When I suggested that we hang up and he could call me back when he had an answer, he insisted that I stay on the line, to no apparent purpose.) One of the first things I asked him was: What if I install an older version of the app? No, said Devan, unfortunately that’s impossible.

Like an idiot, I spent about 24 hours believing him. Then I decided to go ahead and do it. Here is the solution:

1) Fully uninstall the app. This means going to the phone settings, then Apps, then Amazon Kindle. First choose “Force Stop” and then “Uninstall”.

2) Go to apkpure.com, search for the Kindle app, and you’ll be presented with a great variety of choices, all representing different vintages of the same app. I chose one from June 2020, two months ago, well before my problems started. Click to download, click to install, and voila. Problem solved.

I hope this works for you too.

Coming soon, I hope: Tricks I’ve discovered for setting up a new Windows 10 machine, which has been something like a fulltime job for me for the past two weeks. Why can’t things just work out of the box?

When I’m in the car, I use my phone as a music player. Sometimes a song comes on that I’m not in the mood to hear. Once upon a time — in fact, once upon a very recent time — I could say “Okay Google. Next song.” Then the current song would stop and a new song would start. It was all part of Google’s awesome — and free — service. The service was imperfect in some minor ways, but mostly it was awesome and free and I was thankful to have it.

Here’s what happens now when I say “Okay Google. Next song.” The perky Google Assistant voice comes on and says something like “Oh, you want a different song? Okay. Let me sing you one.” Then the perky assistant sings some stupid little jingle for me, and then it returns me to the song I was trying to bypass. My only options at that point are to either a) listen to the rest of the unwanted song, b) try again and have the same thing happen again, which approximately triples my frustration level with each iteration, or c) fumble with my phone, call up the music player, search for the little “next song” button, push it, and try to put the phone back down before I drive into a lamppost. The pattern I’ve developed is to do b) approximately three times, then do c). I hope I’m still alive by the time you read this blog post.

Okay, so the service is still free, and still mostly awesome, right? But I am furious and I think I have a right to be. Let’s review the bidding here. Google has deliberately done the following:

- Disabled the good and useful “next song” feature, for no apparent reason.

- Trained its Assistant to mock its users when they try to invoke that longtime feature.

- Done so in a way that is sure to drive those users into a state of combined frenzy and distraction while they are driving.

Let’s be clear: Mocking users and driving them into a state of frenzy seems to me to be the only conceivable reason for the whole “Here, I’ll sing a song for you, ha ha” bit. I am willing to bet you at substantial odds that no user requested this mockery. It’s apparently put there by Google (or perhaps by a rogue programmer on his last day of work, and overlooked by a lethargic quality control team) for the sole purpose of pissing people off and giving the folks at Google a good chuckle, without regard for possible deadly consequences. It seems to me to be roughly the moral equivalent of throwing watermelons off overpasses.

And just to make that analogy fair: If someone, through sheer technical brilliance and the goodness of his heart, ever designs the world’s most awesome overpass, builds it at his own expense, offers it to the world for free, maintains it for years, and then one day starts throwing watermelons off it — the main thing I’m going to remember is the watermelons.

There are about a million reasons why I hate my iPhone, but this one pretty much sums it all up.

There are about a million reasons why I hate my iPhone, but this one pretty much sums it all up.

On my phone, I’ve got quite a few files that were not downloaded from any of my other devices. These include pictures I’ve taken with the phone itself, pdfs I’ve downloaded through the phone’s browser, etc.

Of course, I’d like to have backups of all these files. And of course Apple makes this as difficult as possible by pushing me to use its abysmal iTunes software for creating the backup.

Now here is what iTunes does: I have photo files with names like IMG_0840.jpg — which, if not terribly descriptive, is at least immediately recognizable as a photo. I have pdfs with names like Dirac.QuantumMechanics.pdf, which is a nice, easily recognizable name. I download everything to my computer via iTunes, and here is a partial directory listing of what I get:

The future, apparently, has not quite yet arrived.

Square Cash promises to be the easy way to transfer money over the Internet. To send you $50, I just send you an email with subject line “$50” and a cc: to cash@square.com — whereupon Square Cash, upon receiving the cc:, moves $50 from my bank account to yours. (First time users get an email from Square asking for their debit card numbers so the transfer can be accomplished.) Sounds like the easiest thing in the world. And it’s free.

Unfortunately, it’s worth about what you pay for it. My experience using Square Cash multiple times over the past several days indicates that, more often than not, Square transfers $50 one direction — and then a few hours later transfers it back in the opposite direction, so that on balance, no money changes hands. When this happens, you get an email from Square saying the reverse transaction was triggered by a “problem”. No further explanation.

Emails to Square are met with standard Customer Service gobbledygook that ignores key questions such as “Why is this happening?” and “What can I do to make it stop happening?” and “Going forward, can I count on it to stop happening?”. (It’s just happened yet again, so apparently the answer to the last question is “No”.)

One feels a little churlish complaining about the quality of a free service. On the other hand, I’d like to spare others the frustrating experience of dealing with Square, never knowing when a transaction is going to be permanent, and getting no useful answers from the powers that be. (All communication is by email; Square is apparently too advanced a company to use phones.)

My advice: These guys are amateurs. Stick with Paypal.

Okay. I’ve never worked as a tech geek, so I’m speculating from ignorance here. Some of you can probably speak with more authority. Perhaps we’ll hear from the reliably acerbic and insightful Doctor Memory, who knows whereof he speaks on this subject (and several others). But to my uneducated eye, it appears that Arnold Kling has got this pretty much dead-on right: The Obamacare mess “is not a technical screw-up, and it will not be fixed by technical people. It is an organizational screw-up.”

What you had here, among other things (and almost of this is paraphrasing Kling) is:

- A bunch of people who had never worked in the insurance business appointing themselves executive officers of the world’s largest insurance brokerage.

- Nobody at the top with the authority to trim features as needed to keep the project manageable.

- No mechanism for the technical staff to challenge the managers, because all of the management decisions were essentially set in stone before the technical staff — i.e. the outside contractors — came on board.

- No clear lines of authority and acceptability.

Private enterprises frequently fail, often for one or more of these reasons. But sometimes they succeed, and that’s largely because sometimes they get this stuff right. The government, by contrast, has no mechanism for getting it right. The people at the top are not industry experts, the features are largely determined by the legislative process, which takes place with absolutely no feedback from the tech geeks who are going to have to implement it, the political system pretty much forces you to put the technical part of the project out for bid and to parcel it out among multiple contractors, eliminating any possibility of ongoing negotiation between the managers and the techies, and on top of all that, nobody’s livelihood is on the line.

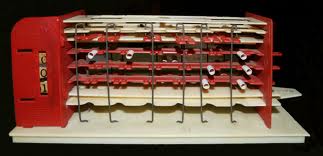

In The Big Questions, I wrote about an absolutely wonderful toy I had as a child. The Digi-Comp I was a completely mechanical computer; it ran on springs and rubber bands, and you built it yourself from a kit. You programmed it by placing little plastic cylinders (cut from drinking straws) on appropriate tabs, and you pushed a lever to run the program. The back of the computer was completely exposed, so you could watch the cylinders and straws and rubber bands push each other around — and see for yourself how those motions implemented the logic of your program and produced a result. As I wrote in The Big Questions, a child with a Digi-Comp I is a child with deep insight into what makes a computer work.

In The Big Questions, I wrote about an absolutely wonderful toy I had as a child. The Digi-Comp I was a completely mechanical computer; it ran on springs and rubber bands, and you built it yourself from a kit. You programmed it by placing little plastic cylinders (cut from drinking straws) on appropriate tabs, and you pushed a lever to run the program. The back of the computer was completely exposed, so you could watch the cylinders and straws and rubber bands push each other around — and see for yourself how those motions implemented the logic of your program and produced a result. As I wrote in The Big Questions, a child with a Digi-Comp I is a child with deep insight into what makes a computer work.

I am delighted that the Digi-Comp I is, after a 40 year hiatus, back on the market, though the modern version substitutes laminated binders board (i.e. high quality cardboard) for plastic. There is, I think, no better gift for a kid who likes computers, or likes logic, or likes knowing how things work.

Now an old friend (who shares my fond memories of this toy) writes to point me to yet another reincarnation of the DigiComp I — as a Lego project! Way cool.

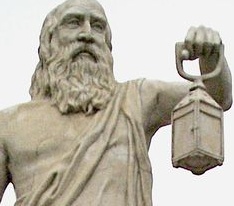

Chapter 8 of The Big Questions is called “Diogenes’s Nightmare” and argues that: 1) In a world of honest truthseekers, there would be no disagreements about matters of fact; 2) In the world we inhabit, disagreements about matters of fact are ubiquitious; therefore 3) in the world we inhabit, there must be precious few honest truthseekers.

Chapter 8 of The Big Questions is called “Diogenes’s Nightmare” and argues that: 1) In a world of honest truthseekers, there would be no disagreements about matters of fact; 2) In the world we inhabit, disagreements about matters of fact are ubiquitious; therefore 3) in the world we inhabit, there must be precious few honest truthseekers.

If you’re looking to ferret out one of those rare creatures, your best candidate might be a man who argues with eloquence and passion against subsidies for the industry where he makes his living. Meet David Bergeron.

David is the founder and president of Sundanzer, which supplies solar powered refrigerators worldwide, based on technology developed by David under contract to NASA. He also really really really understands why subsidizing solar technology is a terrible idea. And when I met him last week, he impressed me so much that I invited him to make a rare guest post here at The Big Questions. So without further ado:

David is the founder and president of Sundanzer, which supplies solar powered refrigerators worldwide, based on technology developed by David under contract to NASA. He also really really really understands why subsidizing solar technology is a terrible idea. And when I met him last week, he impressed me so much that I invited him to make a rare guest post here at The Big Questions. So without further ado:

In a recent Economist on-line debate, the affirmative motion “This house believes that subsidizing renewable energy is a good way to wean the world off fossil fuels” was surprisingly defeated.

In his closing remarks, the moderator softened his strident opposition to the negative case, even admitting that “subsidizing renewable energy, is wasteful and perhaps inadequate to address climate-change concerns.”

The debate, indeed, reopened the question whether anthropogenic greenhouse-gas forcing was a serious planetary environmental concern. But such focus short-changed what I think is the more important question for the Economist. Not only are the renewable-energy subsidies (such as for solar) wasteful and potentially insufficient, they are outright diabolical if indeed there is a looming environmental crisis.

How secure is Internet security? A team of researchers recently set out to crack the security of about 6.6 million sites around the Internet that use a supposedly “unbreakable” cryptosystem. The good news is that they succeeded only .2% of the time. The bad — and rather shocking — news — is that .2% of 6.6 million is almost 13,000. That’s 13,000 sites with effectively no security. The interesting part is what went wrong. It’s a gaping security hole that I’d never stopped to consider, but is obvious once it’s pointed out.

I haven’t been able to find the exact quote, but unless my memory is playing tricks, Martin Gardner once posed the question “What modern artifact would most astonish Aristotle?”, and concluded that the answer was a Texas Instruments programmable calculator that could be taught to execute simple series of instructions. That was, roughly, 1975.

Here is what my iPhone does: It listens to the radio and tells me the name of the artist, song and album. It scans bar codes and tells me where to get the same item cheaper. It gives me step by step directions to anyplace I want to go. It points me to the nearest public bathroom. It recommends restaurants, based on cuisine, price, and proximity. It plays any music I want it to play, and it recommends new music based on what it’s learned about my preferences. It shows me a photograph of the entire earth and lets me slowly (or quickly) zoom in on my (or your) front porch. It takes pictures. It takes videos. It lets me edit those pictures and videos. It photographs 360 degree panoramas. It plays movies. It plays TV shows. It displays pretty much any book, newspaper or magazine I want to read. It reminds me where I parked my car. It lets me draw rough sketches of diagrams with my fingers and makes them look professional. It allows me to accept credit cards. It takes dictation. It checks the stock market or the weather with the push of a button. It reminds me of my appointments. It lets me browse the Web. It shows me my email. It locates and summons nearby taxicabs. It turns itself into a carpenter’s level. It turns itself into a flashlight. It makes phone calls. It makes video calls. And, oh yes — it has a calculator.

Now who would have been more astonished? Aristotle confronted with Martin Gardner’s calculator, or the Martin Gardner of 1975 confronted with my iPhone? I’m going to say it’s a close call.

So after futzing around with one clunky inadequate free product after another, I finally plunked down an amazingly reasonable $59 for the AVS4you software suite, which unlike everything else I’ve tried, actually works, and works well. This has allowed me, pretty much painlessly, to re-create much better versions of some of the videos that I’ve posted here in the past. (Better, that is, in terms of quality, and in terms of format, and in terms of file size.)

There is still, of course, the inevitable tradeoff between better quality on the one hand and less bandwidth on the other. I think I’ve found the sweet point, but am still experimenting.

The current batch of experiments is here. If these download too slowly, or are frustrating to watch for other reasons (other than, perhaps, the content, which is another matter) I’d like to know about it. If they work for you, I’ll be glad to know that too.

PS: It seems crystal clear that these work much better (in the sense of not stalling) in .flv format than as, say, .mp4, even when the flv files are much bigger, and I have the vague sense that everybody in the world except me understands exactly why. Do educate me.

Edited to add, a decade later: The statement that flv works better than mp4 has been negated by the march of technology.