If you’re a novice investor, looking to get into anything from the stocks to Bitcoin, someone is going to tell you that you can reduce your risk by Dollar Cost Averaging — that is, investing the same dollar amount every month. That way, this person will tell you, you are buying more of the asset when its price is low and less when it’s high.

Please do not take investment advice from this person.

I explained in The Armchair Economist why the above argument is just plain wrong, and why Dollar Cost Averaging is actually riskier than a Readjustment strategy where you invest (say) $1000 and then periodically adjust your total investment up or down as necessary to maintain its value. The logic is compelling. But the sort of people who Dollar Cost Average tend not to be the sort of people with much of an appetite for logic. So today let’s go down a different road. I’ve actually done some calculations to show you how the two strategies are likely to pan out.

Imagine a (very volatile) asset, currently selling for $1, which either doubles or halves in value each month, with equal probability. [I know, I know, the asset you’re looking to buy behaves very differently than this one. So feel free to make some other set of assumptions and re-do my calculations. You won’t get exactly the same outcomes, but you’ll probably get outcomes that are similar in spirit.]

Now let’s imagine one hundred Dollar-Cost Averagers, each investing one dollar per month for 10 months. At the end of that ten months, the average investor will be ahead by about $30. That’s not bad.

Let’s also imagine one hundred Readjusters who each invest $11.83 up front and then, at the end of each month, either withdraw or deposit funds to bring their investment right back to $11.83. Why $11.83? Because that way, these hundred Readjusters will earn, on average, exactly the same $30 that the Dollar-Cost-Averagers earn over the course of ten months.

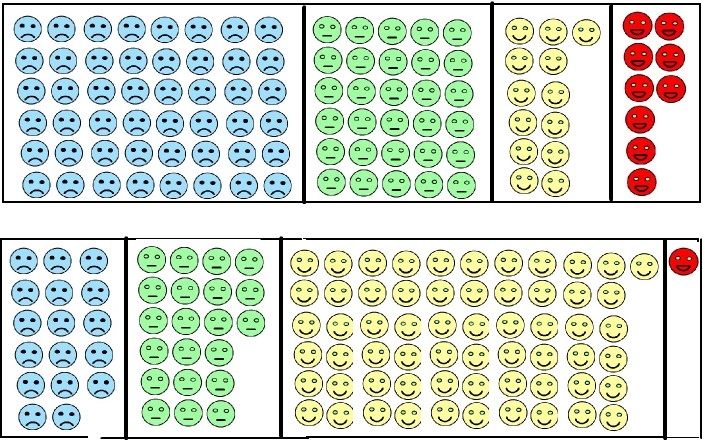

Okay, both strategies do equally well on average. But of course, if you’re one of these investors, you probably won’t be average. So I set my computer to calculating the distribution of outcomes for each group. Here is the result, with the DCA investors on top and the Readjustment investors on the bottom:

The blue guys have actually lost money. The green guys haven’t lost anything, but they’ve gained less than the average $30. The yellow guys have done better than average, and the red guys have done better still, earning over $90, which is three times the average.

Here’s the good news for the Dollar Cost Averagers: Nine of them have earned over $90, whereas only one Readjuster has earned over $90. That’s pretty much the end of the good news. In the money-losing blue category, there are far fewer Readjusters than Dollar-Cost-Averagers — about 17 versus 48. That’s right; almost half the Dollar-Cost-Averagers lose money, while only about 1/6 of the Readjusters do. 61% of the Readjusters are in the very happy yellow category, earning between $30 and $90. Only 13% of the Dollar-Cost-Averagers make it into that bracket.

Does that prove that Dollar-Cost-Averaging is inferior to Readjustment? Of course not. It all depends on what you’re looking for. Dollar-Cost-Averagers are more likely to lose money, and more likely to earn below-average returns, but in exchange, they get a 9% chance of extraordinary success while their Readjusting neighbors have only a 1% chance. Maybe that’s a gamble you want to take. That’s fine. In other words, it makes perfectly good sense to choose Dollar Cost Averaging in order to increase your risk. The guy who told you to use it to decrease your risk is still 100% wrong.

There are, of course, various real world considerations that got left out here. Different investment strategies, for example, have different tax consequences, and you might want to modify your strategy for that reason, but there’s no reason to think that after those modifications, you should be doing anything like Dollar Cost Averaging.

I want to reiterate that even before I did these calculations, I knew (at least roughly) how they were going to come out, because I trust the underlying logic (which, again, can be found in The Armchair Economist). The larger moral is that logic is trustworthy.

The Intelligent Design folk tell you that complexity requires a designer.

The Intelligent Design folk tell you that complexity requires a designer.