Okay, this one’s almost too bizarre for words. First, Paul Krugman makes an argument that ignores the existence of corporate dividends. Then, pretty much everybody in the world points out his error. Then, he admits his error, but, true to form, takes an irrelevant swipe at his critics. But in this case, the irrelevant swipe is: “Aha! You’ve just admitted that corporations pay dividends! So much for your past claims that corporations pay wages!”

Umm…Paul? They pay both. I’d lift Krugman’s own favorite dismissive phrase and say “That’s Economics 101”, but actually it’s probably standard knowledge among middle schoolers.

To review the details:

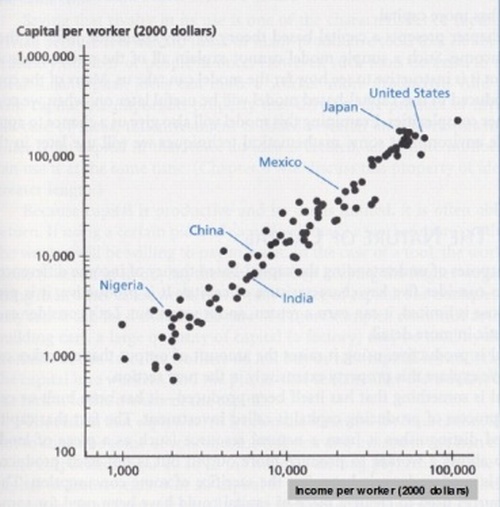

First, Krugman reposted (from the website of a left-wing advocacy group) a highly misleading chart purporting to illustrate the federal tax burdens borne by various income groups. The chart accounts for payroll and income taxes, but omits corporate taxes, thereby making the burden on high-income tax payers appear substantially smaller than it is, because corporate taxes reduce dividends which are disporportionately paid to high-income taxpayers.

Next, he got called on it by lots and lots of people, including, for example, Greg Mankiw.

Next, Krugman acknowledged his error. But, as always, he did so with the least possible grace, suggesting that his critics, by virtue of pointing out Krugman’s mistake, have somehow undermined their own principles.

In particular, his position is that by acknowledging that corporate profits benefit shareholders, “conservatives” have undermined their own ability to claim that corporations benefit anyone other than shareholders (e.g. workers). He relies, in other words, on the cockamamie notion that if something is good for group A, it can’t possibly also be good for group B.

Continue reading ‘In Which Paul Krugman Leaves Me At a Loss for Words’