Now the physicists know what it was like to be an economist in 1978.

Archive for the 'Current Events' Category

No matter how this election turns out, the next president of the United States will be a crackpot.

Donald Trump thinks you can fight Covid with bleach injections. Kamala Harris thinks you can fight inflation with price controls.

No, let me correct that. What Trump actually said was that it would be “interesting to check” on whether you could fight Covid with bleach injections. What Harris actually said was that you can fight inflation with price controls.

On that basis, I’d have to conclude that Harris is the more delusional of the two. Unfortunately, Trump has offered me plenty of additional evidence that he’s right up there in Harris’s league. But she’s made it pretty clear he’ll never actually surpass her.

Recognizing that I know no more about politics than most of you, and that I have no notable record as a political prognosticator, here is my prediction, as of about a half hour before the second Republican presidential debate: Doug Burgum breaks out of the pack with strong attacks on Donald Trump.

Recognizing that I know no more about politics than most of you, and that I have no notable record as a political prognosticator, here is my prediction, as of about a half hour before the second Republican presidential debate: Doug Burgum breaks out of the pack with strong attacks on Donald Trump.

Why? First, he needs a Hail Mary. Second, he needs it tonight, or there’s almost no chance he makes it into the third debate. Third, among the various Hail Mary’s available to him, this seems the most likely to pay off.

Arguably, they all need Hail Mary’s. But those (i.e. most of them) who have refused to substantially attack Trump in the past can’t use this particular Hail Mary without being called out for flip-flopping. (Burgum doesn’t have to worry so much about this, because almost nobody has paid any attention to anything he’s said yet.) Also, Burgum is the one who most needs to get this done tonight, with little prospect of going on otherwise.

A couple of hours from now, you can tell me why I got this wrong.

I am glad I don’t live in a country where the penalty for criminal behavior includes having your tax returns released to the public.

I am doubly glad I don’t live in a country where the penalty for criminal behavior includes having your tax returns released to the public before you are convicted and indeed before you are ever charged.

I am triply glad that I don’t live in a country where the penalty for criminal behavior includes having your tax returns released to the public at the whim of your political opponents.

And I am quadruply glad that I don’t live in a country where those political opponents get to invent penalties that are not envisioned by any statute.

I wish many things for Donald Trump, and I am sure he would not want me to get most of my wishes. But it would be an outrage for the Ways and Means Committee of the House to release his returns under the current circumstances, where, it seems to me, the release is clearly intended as a punishment for some very bad acts that very clearly occurred.

On the other hand: I have long argued (see Chapter 15 of The Armchair Economist) that when voters make choices on the basis of promises that are ultimately not kept, they should have legal recourse in the form of a lawsuit against the politician who broke those promises. In 2016, Donald Trump repeatedly promised to release his tax returns as soon as they were not “under audit”. It’s not at all clear to me why this promise would have changed anyone’s vote, but presumably Trump (who has presumably thought about this harder than I have) believed it would sway at least some voters; otherwise why would he have made such a big deal about it?

In my ideal world, there would be a class-action suit against Trump by voters who relied on his 2016 promise to release these returns, and, after a trial, he might be ordered to fill the breach by releasing those returns today. One could argue that the Ways and Means Committee is simply bringing about my desired outcome by other means.

But: First, as I just said, in my ideal world, the order to release the returns would come after a trial. We have not had that trial. And second, I am actually very very glad that I do not live in a world where my personal policy preferences are implemented without first going through some sort of process whereby they become law. Like so many of my best ideas, this one is not yet a law. I’m glad I do live in a country where (by and large) non-laws are not enforced, even when I believe they ought to be laws.

Let’s try to make the best possible case for restricting abortion and see how far we get.

To make that case as strong as possible, let’s start from the presumption that we care about the interests of the unborn in just the same way as the interests of the born.

Now caring about someone’s interests is not a sufficient reason to defer to those interests, because there are usually competing interests that have to be weighed in the balance (in this case the interest of the mother). Often, competitions between interests play out in the marketplace, so that policymakers are unnecessary — if you and I both want the same house, we settle that conflict by bidding for it.

But sometimes markets don’t work very well, and then there’s a policy problem to resolve. For example, suppose your boat happens to be in the vicinity of my dock when it springs a leak and starts to sink. The only way to save the boat is to tie it to the dock. If I happen to be out sunning myself on that dock, we can strike a bargain. But if I’m nowhere to be found, the law enforces the outcome that we presumably would have reached and allows you to tie up to my dock.

The same fundamental problem applies in the case of abortion. You might be willing to pay a substantial fraction of your lifetime income to prevent yourself from being aborted, but at the time of the abortion decision, those negotiations are quite impractical. So by analogy with the boat and the dock, one might argue that the law should enforce the outcome that we presume those negotiations would have led to, by prohibiting the abortion.

But if that argument is correct, it applies to the unconceived as well as to the unborn — that is, it seems apparent that most adults who are glad they were not aborted are equally glad that they were conceived in the first place, and would have agreed to pay just as much to bring about the conception as to prevent the abortion. This suggests that if the law should strive to prevent abortions, it should also strive to bring about a considerable number of additional pregnancies.

But even if you accept that argument, it is not an argument for involuntary impregnation; it is at best an argument for subsidized impregnation. It’s a general principle of cost-benefit analysis that taxes and subsidies are almost always better than mandates, because they allow for different individuals to make different choices that account for circumstances invisible to the policymaker. That’s why it’s better to tax carbon than to mandate gas mileage. And likewise, even if you accept the anti-abortion argument, it is not an argument for banning abortion; it’s at best an argument for taxing abortion.

How big should the tax be? Another principle of cost-benefit analysis is that everyone’s interests should count equally. So if we take all of this seriously, then one additional pregnancy compensates for one additional abortion — one potential life is lost; another potential life is gained; and that’s a wash. Therefore the policy implication is that abortion should, at most, be taxed at a rate necessary to fund the subsidization of one additional pregnancy.

In other words — if A has an abortion but simultaneously coughs up enough money to induce B to become pregnant and carry a baby to term, then even if you buy the market-failure rationale for restricting abortion, the world as a whole is no worse off than before — and in fact better off, because the pregnancy has been voluntarily transferred from A to B. If A is willing to pay that price, I can’t find any reason to disallow it.

(In fact, one could well argue that the mere fact of A’s pregnancy is no reason to impose a tax burden on A — if A has an abortion, the rest of us can perfectly well pick up the tab to enlist B as a substitute, so that A doesn’t need to be taxed at all. I’m putting that argument aside only because I’m trying to bias the outcome in favor of a large deterrent.)

That sets a maximum penalty for abortion. If you’re skeptical of the initial premise that we care about unborn people the same way we care about everyone else (or skeptical of the market-failure argument) then the penalty should be lower — maybe a lot lower. In no case would you want to impose a ban.

To avoid those conclusions, you’d need (for starters) a clear reason to favor the conceived-but-unborn over the not-yet-conceived. Unless you’re prepared to descend into deontology, I think that reason is going to be hard to come by, again because I am exactly as happy to have been conceived as I am to have been unaborted. And even if you find that reason, you might be able to use it to argue for a higher tax but still not, I think, an infinite one.

Edited to add: The more I think about this, the more it seems to me that the correct conclusion is that if we, as a society, care about preventing abortions then we, as a society, should be subsidizing births, and the cost of those subsidies should be spread widely, so that the right tax on abortion should in fact be zero.

I thought the whole rationale for taxing capital gains in the first place was that we want to discourage inefficiently frequent trading.

If you buy that rationale, then the last thing you want to do is tax unrealized gains. If you don’t buy that rationale, then why tax any gains?

Unless, of course, you’re more into thuggery than rationales….

In the days following the 2020 presidential election, fears ran rampant that Donald Trump, having lost the election, would try to do something truly crazy like launch a missle strike or deploy troops to prevent an orderly transition. But among the grownups at the Pentagon, there was one even bigger fear:

For the Joint Chiefs, the biggest worry was the revival of one of Trump’s hobbyhorses: pulling troops out of Afghanistan, what he had called the “loser” war. A long line of advisers—Mattis, McMaster, Kelly, Mike Pompeo, and former secretary of state Rex Tillerson among them—had repeatedly discouraged this idea from the first time Trump brought it up in 2017. American intelligence units in the region needed military support to keep up their work. The United States had hundreds of millions of dollars’ worth of equipment and vehicles on the ground that would have to be methodically removed, or else they could be confiscated by the Taliban and make enemy forces that much better equipped to terrorize civilians and attack the Afghan government. Even if Trump decided to dramatically reduce forces in the region, his generals and top advisers warned him that pulling out of Afghanistan wasn’t as simple as putting a bunch of soldiers on a bus and heading out. Withdrawal had to be executed carefully and in stages, protecting each flank and helping the Afghan government remain stable.

…

Pentagon leaders worried about a Saigon situation, with a chaotic last-minute exit and desperate people rushing to a rooftop to catch the last helicopter out. The Joint Chiefs began preparing for the possibility. If the president ordered a military action they considered a disaster in the making, Milley would insist on speaking to the president before passing on the order, so he could advise against it. Under this plan, if the president rejected Milley’s counsel, the chairman would resign to signal his objections. Then, with Milley out of the picture, the Joint Chiefs could demand in turn to give the president their military advice. This would buy time. In informal conversations, they discussed what would happen if they, too, got the brush-off from Trump. They considered falling on their swords, one by one, like a set of dominos. They concluded they might rather serially resign than execute the order. It was a kind of Saturday Night Massacre in reverse, an informal blockade they would keep in their back pockets if it ever came to that.

— Carol Leonnig and Philip Rucker

I Alone Can Fix It: Donald J. Trump’s Catastrophic Final Year

Okay, so according to the news, the FBI has recovered the bulk of the Bitcoins paid as ransomware by the Colonial Pipeline Company, by acquiring the private key to the address where those Bitcoins were stored.

No news source I’ve seen has offered anything approaching an answer to the question: How did the FBI get ahold of that private key? Did the criminal masterminds behind the ransomware attack just leave it, unencrypted, on a hard drive or a piece of paper in a place where the FBI was likely to look?

At first I thought the most likely answer was that the FBI must have traded something for that key — say some sort of immunity (either from prosecution or, maybe, from something like a beating). But on second thought, it occurs to me that maybe hiding a private key from the FBI is trickier than it sounds.

I know plenty of good ways to hide private keys from thieves. You can write your key on a piece of paper (or better yet, etch it in metal) and store it in a safe deposit box. Or, for extra security (say if you’re worried about bank employees accessing those boxes), put half of it in one safe deposit box and the other in another, at a different bank. Or, if you’re worried about one of those banks being reduced to rubble in an earthquake or a terrorist attack (in which case no criminal could get your key, but neither could you), you can break the key into three parts, store parts A and B at Bank One, parts B and C at Bank Two, and parts A and C at Bank Three. Any one bank can disappear and you can still recover your entire key.

That secures your keys and makes them safe from criminals, but it does not make them safe from the FBI, which has the power to issue subpoenas to all of your banks and recover the contents of your safe deposit boxes. So maybe hiding your keys from the FBI is harder than it appears.

So let me try again: After etching them on metal, store parts A and B at Location One, parts B and C at Location Two, and parts A and C at Location Three, where you expect to have access to all of these locations (and only really need access to two of them) but none is particularly tied to you — i.e. not your house, not your car, not your safe deposit box. Maybe underground locations in the woods, though that feels a little sketchy to me. And then of course you might want to keep some sort of written record of those locations, which the FBI can find when they search your house or safe deposit box, whereupon they might wonder what’s so interesting about those locations that you felt the need to keep track of them….

You might think the safest thing is to memorize your key (or a mnemonic English phrase from which the key can be derived) and leave no record of it anywhere except in your own brain. That’s fine until dementia starts to set in, or until you’re hit by a bus (in which case your heirs are out of luck, though you might or might not care about that). Or you can leave written clues to the mnemonic that only you will be able to decipher, like “Word 9: The secret nickname I had for the girl I had a crush on in third grade”. This is of course also subject to the dementia problem.

So. Suppose you’re a master criminal, storing your ill-gotten gains as Bitcoins, which you want easy access to at all times for yourself (and maybe your heirs), but you want to keep completely inaccessible from law enforcement agencies with unlimited subpoena power. What’s your plan?

Update: More recent news reports indicate that the coins were seized from a custodial account — based in the United States, no less. In other words, my sarcastic reference above to “criminal masterminds” was not nearly as sarcastic as it should have been. It’s not that these guys failed to think of a clever scheme for hiding their keys; it’s that they never even bothered to try. The more interesting question, then, is how does Bitcoin fall 10% on the “news” that if you let someone else hold your private keys, you can lose your Bitcoins. (“Not your keys, not your coins”, as the saying goes.) The best answer I have (not just for this event but for a lot of Bitcoin volatility in general) is that anything even slightly unsettling leads to a small drop in prices, whereupon heavily leveraged investors fail to meet their margin calls, which leads to big selloffs. But that’s not a full answer until someone fleshes out the part where more sophisticated investors fail to jump in and take advantage of this buying opportunity. So maybe the dip, despite the coincidental timing, had nothing to do with the seizure.

The death of Bernie Madoff reminds me that I never understood why he was so vilified. He ran a Ponzi scheme. All of his investors knew it was a Ponzi scheme. They chose to get in, and gambled that they could time their exits just right. Some succeeded, some failed. So Madoff was the moral equivalent of a bookmaker (and not the kind of bookmaker who employs violence to enforce collections). He catered to a preference that some might call a vice. Where’s the problem?

The death of Bernie Madoff reminds me that I never understood why he was so vilified. He ran a Ponzi scheme. All of his investors knew it was a Ponzi scheme. They chose to get in, and gambled that they could time their exits just right. Some succeeded, some failed. So Madoff was the moral equivalent of a bookmaker (and not the kind of bookmaker who employs violence to enforce collections). He catered to a preference that some might call a vice. Where’s the problem?

There would be a problem if anybody had believed Madoff’s claim that he could earn a consistent 10% in any kind of market conditions, but it’s hard for me to imagine who that “anybody” might be — and if he or she does exist, then I don’t think it’s incumbent on the rest of us to protect an investor who is so willfully naive. The fact that he not only claimed to return 10% in every kind of market condition but actually did so constituted something like proof postive that he was running a Ponzi scheme, for anyone who cared to take notice.

So I think Madoff’s “lies” go into the same category as the alleged “lies” of Barack Obama when he said that under Obamacare, anybody who liked his/her old health insurance policy would be able to keep it. Nobody capable of arithmetic could have believed such an outlandish statement — unless they gave it no thought whatsoever, in which case even if they were fooled, they were fooled about something they apparently didn’t care about.

In other words: It’s not a lie if nobody believes it.

The scandal, I think, is that public resources were used to recover the losses of those who took the Madoff gamble and lost.

Just in case you thought the change of administration meant an end to stupid and evil trade policies, CNN reports that “President Joe Biden will sign an executive order Monday aimed at boosting American manufacturing, setting in motion a process to fulfill his campaign pledge to strengthen the federal government’s Buy American rules.”

I already knew this, but it’s nice to be reminded: Caitlin Flanagan is a national treasure.

Marty Makary, Professor of Health Policy at Johns Hopkins, as quoted by Alex Tabarrok:

Ironically, those in the Oxford-AstraZeneca trial who inadvertently received half the initial vaccine dose had lower infection rates

Makary and Tabarrok’s main point (with which I fully agree) is that it’s criminally stupid for the FDA not to approve the A-Z vaccine immediately — and their main argument would stand with or without the observation about infection rates.

But I’m quoting the same observation for an entirely different reason: To point out that sometimes you need economics to explain the medical data.

In particular: Half-dosed subjects will generally have fewer side effects. Subjects with fewer side effects will think it more likely that they’ve gotten the placebo. Subjects who think they’ve gotten the placebo are going to continue taking more precautions with masks, social distancing, etc. Therefore it’s entirely plausible that half-dosed subjects will have lower infection rates.

Thanks to Romans Pancs for pointing me in this direction, and reminding me of the Thanksgiving puzzle that I posted here.

Over four years ago, I published my answers to some frequently asked questions about Donald Trump. Here is some of what I said then:

Over four years ago, I published my answers to some frequently asked questions about Donald Trump. Here is some of what I said then:

…

Is Donald Trump batshit crazy? Obviously yes. He seethes with personal resentments, all of which loom larger in his mind than, well, anything, and appears genuinely incapable of fathoming the possibility that there are people who don’t particularly care whether someone high or low has been “unfair” to Donald J. Trump. He claims to believe that Hillary Clinton’s policies would be disastrous for the country, yet works to undermine the Republican congressional and Senate candidates who stand as a bulwark against those policies, because preventing a national disaster is less important than petty vengeance against those who have failed to pay Trump his due respects. Moreover, he seems genuinely baffled by the suggestion that anybody anywhere might prioritize things differently. He has, as I’ve said before on this blog (and as countless others have said, sometimes more poetically) the mental, emotional and moral maturity of a four-year-old, with an attention span to match.

Is being batshit crazy a disqualification for the position of Commander in Chief of the armed forces of the United States of America? Hell yes.

Summary: I do not know and I do not much care whether Donald Trump is a racist or a serial groper, except insofar as I wish nobody were a racist or a serial groper. When I’m deciding who to support for President, I care about things that will affect his or her performance in office. In Trump’s caase, I believe the xenophobia is a sufficient disqualification, though I think one could reasonably argue that, given the shortcomings of the alternatives, we should not be so quick to disqualify. But I do not think that one could reasonably say the same about the paranoia, narcissism, and all the related mental instability. The next time Trump goes off on an incoherent rant — and he will — try imagining him in command of the United States Army. Take that image into the voting booth.

I’m not always right, but I’m not always wrong either.

Can one of my more knowledgeable readers answer this?

If there are 23 cabinet positions, of which, say, 6 are vacant and 17 are occupied, what counts as a majority for purposes of the 25th amendment? Is it half of 23 or half of 17?

I realize there are additional ambiguities in the 25th amendment, which talks about “principal officers of the executive department”, without ever using the word “cabinet”. But I think I understand those issues. I’d just like an answer to the specific question above.

I hold this truth to be self-evident: It is downright crazy to try to distribute vaccines without using prices. I said as much last week.

The question then becomes: How should those prices be implemented?

Method I: Distribute vaccine rights randomly and let people trade them. This suffers from the fact that you can’t know how much the vaccine is really worth to the people you’re bargaining with, which is a barrier to efficient bargaining.

My immediate instinct (which I still think is a pretty good one) is (after pre-vaccinating certain key groups like first responders and health care workers) to give everyone a choice: You can have your vaccine now, or you can have a check for (say) $500 and your vaccine in six months. This suffers from the need to get the price right (presumably involving some trial and error) but I stand by it as far far better than the Soviet-style central planning we’re about to actually get.

But now Romans Pancs has done far better than I have, by actually thinking about the details of the optimal auction design and getting them right. His paper is here. (You’ll need to sign up for a free account before downloading.) Anyone who actually cares about getting vaccines distributed efficiently should start by reading this paper.

Here is a scenario not unlike many that could well play out in the near future, courtesy of our friends at the Centers for Disease Control:

- Edna, age 65 and retired, lives alone and likes it. She gets along well with her neighbors but prefers not to socialize much. She’s entirely comfortable with her Kindle, her Netflix, and her Zoom account, which she uses to keep in touch with her family. She does look forward to the day when she can hug them again, but for the time being, she’s wistfully content.

- Irma, age 62 and retired, lives alone but mostly lives to dance. In normal times, she’s out dancing five nights a week, and out with friends most afternoons. Confined to her apartment, she’s feeling near suicidal.

- Tina, age 65 and a corporate CEO, has discovered, somewhat to her surprise, that she can do her job via Zoom as well as she can do it from her office. It took a little getting used to, but with all the time she saves commuting, she’s actually able to work more effectively, and everything’s humming along just as it should.

-

Gina, age 58 and also a corporate CEO, has a very different management style. She’s accustomed to popping into her managers’ offices unannounced at all times of day to keep tabs on what’s going on, and she’s found that this way of working is extremely effective for

her. Since the pandemic started, she’s lost her grip and the corporation is foundering.

Now: A vaccine becomes available. The CDC decides that people over 65 will be near the front of the line to receive it.

Question 1: Should Edna be allowed to sell her place in line to Irma? Should Tina be allowed to sell her place to Gina?

Question 2: Do you think the CDC will allow that?

I am quite sure that the answer to Question 1 is yes, and nearly as sure that the answer to Question 2 is no. Which means something is wrong.

It is tragic that so much of pandemic-management policy has been made in defiance of basic science. It is equally tragic that so much policy is about to be made in defiance of basic economics. Because if there’s one thing that economics teaches us, it’s that you cannot distribute a scarce resource efficiently unless you use the price system. No bureaucrat at the CDC has enough information to distinguish Edna from Irma, or Tina from Gina. Therefore they won’t even try.

Essentially everyone understands that it would be insane to try to distribute food or housing or pretty much anything else without using prices. But when it comes to Covid vaccines, the reasoning seems to be that vaccine distribution is uniquely important, so we should do a uniquely bad job of it. Go figure.

If you think it would be a nightmare for all the Edna/Irma and Tina/Gina pairs to negotiate individual contracts, there’s a simpler way to accomplish the same thing: Let Irma and Gina buy their way to the front of the line, then take all the money you collect and redistribute it to the population as a whole so that Edna and Tina get their shares. In other words, let the price system do its job.

|

|

Alabama Senator-elect Tommy Tuberville is quoted as saying:

I tell people, my dad fought 76 years ago in Europe to free Europe of socialism. Today, you look at this election, we have half this country that made some kind of movement, now they not believe in it 100 percent, but they made some kind of movement toward socialism. So we’re fighting it right here on our own soil.

Over at MSNBC, Steve Benen responds:

It’s true that Tuberville’s father fought in France during World War II, but if the senator-elect thinks the war was about “freeing Europe of socialism”, he probably ought to read a book or two about the conflict.

Apparently, reading a book or two about World War II is not a prerequisite for writing commentary at MSNBC. I wonder which of the following points Mr. Benen has overlooked:

- Our primary opponents in the European conflict were known as “the Nazis”.

- Naziism is/was a dialect of socialism.

I’d elaborate, but I’ll keep this short just in case Mr. Benen drops by this blog. Apparently he doesn’t like to read very much.

If you’re worried about the president subverting the electoral process, you might pause to give thanks for the electoral college. If the election were conducted by a federal authority, or if any single authority were responsible for aggregating all the votes from around the country, it’s a fair bet that either this president or some future president would be exploring ways to intimidate that authority.

How is it that so many of the very same people who express grave concern about a president clinging to power by manipulating or ignoring vote totals are so quick to disdain the institution that makes it essentially impossible for him to do exactly that?

It’s always dangerous to centralize power. It’s doubly dangerous to centralize the power to decide who wields power.

More thoughts on this can be found in my piece in today’s Wall Street Journal.

There are (at least) two ways to test the efficacy of a vaccine. The Stupid Way is to administer the vaccine to, say, 30,000 volunteers and then wait to see how many of them get sick. The Smarter Way is to adminster the vaccine to a smaller number of (presumably much better-paid) volunteers, then expose them to the virus and see how many get sick.

A trial implementing the Smart Way is getting underway at Imperial College London. In the United States, we do things the Stupid Way, at least partly because of the unaccountable influence of a tribe of busybodies who, having nothing productive to do, spend their time trying to convince people that thousands of lives are worth less than dozens of lives. Those busybodies generally refer to themselves as Ethicists, but I think it’s always better to call things by informative names, so I will refer to them henceforth as Embodiments of Evil.

Last night, while I was attempting to calculate the amount of damage that these Embodiments of Evil have caused, I was interrupted by a knock on my door. It turned out to be a man from Porlock, who wanted to consult me on some mundane issue. At first I tried to turn him away, explaining that I was in the midst of a difficult calculation and could not be distracted. But my visitor brought me up short by reminding me that the economist’s job is not just to lament bad policies, it’s also to figure out ways to circumvent them. So we put our heads together and this is what we came up with:

First, design a vaccine trial that is, to all appearances, set up the Stupid Way. We vaccinate people, we let them go their own ways, and we track what happens. But we add one twist: Any volunteer who gets sick after being vaccinated receives an enormous payment. Call it something like “Compassionate Compensation”.

Here are the advantages:

Continue reading ‘Vaccine Testing: The Smart and Sneaky Way’

Here are the opening paragraphs of my (paywalled) op-ed in today’s Wall Street Journal.

For nearly four years, I’ve looked forward to voting against Donald Trump. But Joe Biden keeps testing my resolve.

It isn’t only that I think Mr. Biden is frequently wrong. It’s that he tends to be wrong in ways that suggest he never cared about being right. He makes no attempt to defend many of his policies with logic or evidence, and he deals with objections by ignoring or misrepresenting them. You can say the same about President Trump, but I’d hoped for better.

The great tragedy of the Trump administration has been that the President’s obvious mental incapacity has tended to discredit, in the minds of the public, even the good policies that he (apparently randomly) chooses to endorse. As a result, many good policies will never get the consideration they’re due.

For example: Trump happens to be right that we can design a system a whole lot better than Obamacare. But he’s never explained why, and he’s never even attempted to sketch out what such a system might look like. This (appropriately, and probably accurately) makes him appear to be an idiot, and therefore (inappropriately) leads the public to dismiss meaningful health care reform as an idiotic policy.

Likewise: Trump happens to be right that lockdowns and other mandates have enormous costs, which need to be weighed against the benefits of fighting a pandemic. But instead of focusing on that important point, he’s garbled it all up with the ridiculous notion that you’d have to be dumb to wear a mask (and no, his occasional weasel words on this subject do not erase his primary message). This (appropriately, and probably accurately) makes him appear to be an idiot, and therefore (inappropriately) leads the public to dismiss meaningful cost-benefit analysis as an idiotic exercise.

There are a thousand more examples; feel free to share your favorites in comments.

I devoutly wish that Ruth Bader Ginsburg had lived on for a very long time. She was fair-minded, thoughtful, and occasionally brilliant. I valued her reasoning even when I disagreed with her conclusions, and because she was a careful thinker, I am confident that there were times when she was right and I was wrong.

I devoutly wish that Donald Trump were not the president of the United States, largely because he is everything that Ginsburg was not.

But clouds have silver linings, and I take great solace in the fact that Trump will (probably) appoint Ginsburg’s successor. History suggests that a Trump appointee will share the Ginsburg characteristics I most admire, and that a Biden appointee would probably not. The world is a complicated place.

A short time ago, in a Universe remarkably similar to our own, a team of researchers investigated racial differences in cognitive skills and concluded, with high degrees of certainty and precision, that the correlation between race and intelligence is zero. They submitted their results to a journal called Science, which is remarkably similar to the journal called Science in our own Universe. The paper was accepted for publication, but the editors saw fit to issue this public statement:

We were concerned that the forces that want to downplay the differences between the races as well as the need for racial segregation would seize on these results to advance their agenda. We decided that the benefit of providing the results to the scientific community was worthwhile.

Which of the following best captures the way you feel about that statement?

A. Bravo to the editors for advancing the cause of truth, even if it might be misused.

B. Boo to the editors for even thinking about suppressing the truth, even if the truth might be misused.

C. WHAT?!?!? Since when is a failure to share the editors’ political priorities a “misuse” in the first place?

D. Both B and C.

E. Other (please elaborate).

My vote is for D. It is outrageously wrong for the editors to even consider using the resources of their journal to promote their private political agenda. It is doubly wrong for them to even consider doing so by suppressing a paper they would otherwise accept. And it is triply wrong for them to even consider imposing on the owners and readers of the journal to support a political agenda that some of those owners and readers will no doubt find deplorable.

I happen to be one of those who deplore the expressed agenda, but that has nothing to do with my point here. The outrage would be exactly as great if the editors were focused on protecting capitalism instead of segregation.

Now let’s come back to our own Universe, where the editors of Science (the real Science) accepted a paper suggesting that a large fraction of the population might already have a sort of pre-immunity to Covid 19, and somehow saw fit to issue the following statement:

We were concerned that forces that want to downplay the severity of the pandemic as well as the need for social distancing woud seize on the results to suggest that the situation was less urgent. We decided that the benefit of providing the model to the scientific community was worthwhile.

As I said, the two Universes are eerily similar. The statements made by the editorial boards in both Universes seem about equally outrageous to me.

The real-world editors, if they cared what I thought, might want to respond that my analogy fails because “the need for racial segregation” is a political stance, whereas “the need for social distancing” is a scientific one. If so, they’d simply be wrong. Biologists have no particular insight into whether people would be happier in a world with both a little more Covid and a few more hugs. If any group is uniquely qualified to estimate the terms of that tradeoff, it’s the economists — but I wouldn’t want the editors of an economics journal making this kind of call either.

I’m glad that the editors did the right thing. I’m appalled they even considered doing the wrong thing, and concerned that this means they might do the wrong thing in the future, and might have done so in the past. It is not okay to suppress truth in the furtherance of a political agenda. It is not okay to presume that all good people share in your agenda, or to co-opt other people’s resources in order to advance it.

(Hat tip to David Friedman, whose blog made me aware of this.)

Walter Block is under fire from a bunch of very silly people, for reasons that he recounts in this week’s Wall Street Journal.

Unfortunately, if you’re not a Journal subscriber that link probably won’t work for you. Fortunately, it doesn’t matter, because these people are as unoriginal as they are silly, and the issues are pretty much the same as they were when a bunch of equally silly people ganged up on Walter six years ago. So you’ll be pretty much caught up if you just re-read the accounts from back then.

You could, for example, re-read my 2014 blog posts titled Block Heads and Chips Off the Block. I’ll even make this easier for you by reposting the first one right here:

The righteously irrepressible Walter Block has made it his mission to defend the undefendable, but there are limits. Chattel slavery, for example, will get no defense from Walter, and he recently explained why: The central problem with slavery is that you can’t walk away from it. If it were voluntary, it wouldn’t be so bad. In Walter’s words:

The righteously irrepressible Walter Block has made it his mission to defend the undefendable, but there are limits. Chattel slavery, for example, will get no defense from Walter, and he recently explained why: The central problem with slavery is that you can’t walk away from it. If it were voluntary, it wouldn’t be so bad. In Walter’s words:

The slaves could not quit. They were forced to ‘associate’ with their masters when they would have vastly preferred not to do so. Otherwise, slavery wasn’t so bad. You could pick cotton, sing songs, be fed nice gruel, etc. The only real problem was that this relationship was compulsory.

A group of Walter’s colleagues at Loyola university (who, for brevity, I will henceforth refer to as “the gang of angry yahoos”) appears to concur:

Traders in human flesh kidnapped men, women and children from the interior of the African continent and marched them in stocks to the coast. Snatched from their families, these individuals awaited an unknown but decidedly terrible future. Often for as long as three months enslaved people sailed west, shackled and mired in the feces, urine, blood and vomit of the other wretched souls on the boat….The violation of human dignity, the radical exploitation of people’s labor, the brutal violence that slaveholders utilized to maintain power, the disenfranchisement of American citizens, the destruction of familial bonds, the pervasive sexual assault and the systematic attempts to dehumanize an entire race all mark slavery as an intellectually, economically, politically and socially condemnable institution no matter how, where, or when it is practiced.

So everybody’s on the same side, here, right? Surely nobody believes the slaves were voluntarily snatched from their families, shackled and mired in waste, sexually assaulted and all the rest. All the bad stuff was involuntary and — this being the whole point — was possible only because it was involuntary. That’s a concept with broad applicability. One could, for example, say the same about Auschwitz. Nobody would have much minded the torture and the gas chambers if there had been an opt-out provision. And this is a useful observation, if one is attempting to argue that involuntary associations are the root of much evil.

For cost-benefit analysis, the usual ballpark figure for the value of a life is about $10,000,000. But I keep hearing it suggested that when it comes to fighting a disease like Covid-19, which mostly kills the elderly, this value is too high. In other words, an old life is worth less than a young life.

I don’t see it.

People seem to have the intuition that ten years of remaining life are more precious than one year of remaining life. That’s fine, but here’s a counter-intuition: An additional dollar is more precious when you can spend it at the rate of a dime a year for ten years than when you’ve got to spend it all at once — for example, if your time is running out. (This is because of diminishing marginal utility of consumption within any given year). So being old means that both your life and your dollars have become less precious. Because we measure the value of life in terms of dollars, what matters is the ratio between preciousness-of-life and preciousness-of-dollars (or more precisely preciousness-of-dollars at the margin). If getting old means that the numerator and the denominator both shrink, it’s not so clear which way the ratio moves.

Instead of fighting over intuitions, let us calculate:

Suppose you’re a young person with 2 years to live and 2N dollars in the bank, which you plan to consume evenly over your lifetime, that is at the rate of $N per year. I’ll write your utility as

Suppose also that you’re willing to forgo approximately pX dollars to avoid a small probability p of immediate death. Then (by definition!) X is the value of your life. (The reasons why this is the right definition are well known and have been discussed on this blog before. I won’t review them here.) This means that

= U(N,N) – (pX/2)U1(N,N) – (pX/2)U2(N,N)

(where the last equal sign should be read as “approximately equal” and the Ui are partial derivatives).

Because you’ve optimized, U2(N,N) = U1(N,N), so we can write

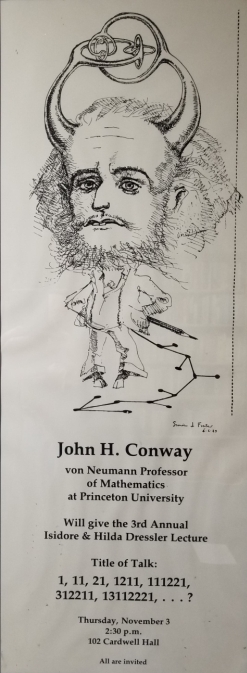

The poster to the left hangs on the wall of my office. Can you figure out the pattern to the sequence? Now can you estimate the size of the nth entry?

The poster to the left hangs on the wall of my office. Can you figure out the pattern to the sequence? Now can you estimate the size of the nth entry?

John Horton Conway died yesterday, a victim of Covid-19. His unique mathematical style combined brilliance and playfulness in equal measure. I came across his “soldier problem” at an impressionable age, and was astonished by the beauty of the solution. You’ve got an infinite sheet of graph paper, with one horizontal grid line marked as the boundary between friendly and enemy territory. You can place as many soldiers as you like in friendly territory, at most one to a square. Now you can start jumping your soldiers over each other — a soldier jumps horizontally or vertically, over an adjacent soldier (who is then removed from the board) into an empty square. The goal is to advance at least one soldier to the fifth row of enemy territory. Conway’s proof that it can’t be done struck me then as utterly beautiful, utterly unexpected, and a compelling reason to learn more about this mathematics business.

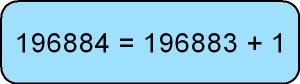

He invented the Game of Life. He invented the system of surreal numbers, a vast generalization of the usual real numbers, designed for the purpose of assigning values to positions in games but adopted by mathematicians for purposes well beyond its original design. (Don Knuth’s book on the subject is a classic, and easy reading). His Monstrous Moonshine conjecture is the reason I own a t-shirt that says:

which I am prepared to argue is the most remarkable equation in all of mathematics. He was the first person to prove that every natural number is the sum of 37 fifth-powers. More than a century after mathematicians first gave a complete classification of two-dimensional surfaces, Conway (together with George K. Francis) found a much better proof. He worked in geometry, analysis, algebra, number theory and physics. And reportedly, he could solve a Rubik’s Cube behind his back, after inspecting it for a few seconds.

Gone now, along with John Prine — another icon of my youth — and too many others. I got the word about Conway just as I was about to go to bed, and am typing this in a state of exhaustion. If I were more awake, it would be more coherent, but it will have to do.

[I am happy to turn this space over to my former colleague and (I trust) lifelong friend Romans Pancs, who offers what he describes as

a polemical essay. It has no references and no confidence intervals. It has question marks. It makes a narrow point and does not weigh pros and cons. It is an input to a debate, not a divine revelation or a scientific truth.

I might quibble a bit — I’m not sure there’s such a thing as a contribution to a debate that nobody seems to be having. I’d prefer to see this as an invitation to start a thoughtful and reasoned debate that rises above the level of “this policy confers big benefits; therefore there’s no need to reckon with the costs before adopting it”. That invitation is unequivocally welcome. ]

| —SL |

The Main Argument

It is a crime against humanity for governments to stop a capitalist economy. It is a crime against those whom the economic recession will hit the hardest: those employed in the informal sector, those working hourly customer service jobs (e.g., cleaners, hairdressers, masseurs, music teachers, and waiters), the young, the old who may not have the luxury of another year on the planet to sit out this year (and then the subsequent recession) instead of living. It is a crime against those (e.g., teachers and cinema ushers) whose jobs will be replaced by technology a little faster than they had been preparing for. It is a crime against the old in whose name the society that they spent decades building is being dismantled, and in whose name the children and the grandchildren they spent lifetimes nourishing are subjected to discretionary deprivation. Most importantly, it is a crime against the values of Western democracies: commitment to freedoms, which transcend national borders, and commitment to economic prosperity as a solution to the many ills that had been plaguing civilisations for millennia.

Capitalism and democracy are impersonal mechanisms for resolving interpersonal (aka ethical) trade-offs. How these trade-offs are resolved responds to individual tastes, with no single individual acting as a dictator. Governments have neither sufficient information, nor goodwill, nor the requisite commitment power, nor the moral mandate to resolve these tradeoffs unilaterally. Before converting an economy into a planned economy and trying their hand at the game that Soviets had decades to master (and eventually lost) but Western governments have been justly constrained to avoid, Western governments ought to listen to what past market and democratic preferences reveal about what people actually want.

People want quality adjusted life years (QALY). People pay for QALY by purchasing gym subscriptions while smoking and for safety features in their cars while driving recklessly. Governments want sexy headlines and money to buy sexy headlines. Experts want to show off their craft. But people still want QALY, which means kids do not want to spend a year hungry and confined in a stuffy apartment with depressed and underemployed parents; which means the old want to continue socialising with their friends and, through the windows of their living rooms, watch the life continue instead of reliving the WWII; which means the middle-aged are willing to bet on retaining the dignity of keeping their jobs and taking care of their families against the 2% chance of dying from the virus.

Suppose 1% of the US population die from the virus. Suppose the value of life is 10 million USD, which is the number used by the US Department of Transportation. The US population is 330 million. The value of the induced 3.3 million deaths then is 33 trillion USD. With the US yearly GDP at 22 trillion, the value of these deaths is about a year and a half of lost income. Seemingly, the country should be willing to accept a 1.5 year-long shutdown in return for saving 1% of its citizens.

The above argument has three problems that overstate the attraction of the shutdown:

- The argument is based on the implicit and the unrealistic assumption that the economy will reinvent itself in the image of the productive capitalist economy that it was before the complete shutdown, and will do so as soon as the shutdown has been lifted.

- The argument neglects the fact that the virus disproportionately hits the old, who have fewer and less healthy years left to live.

- The argument neglects the fact that shutting down an economy costs lives. The months of the shutdown are lost months of life. Spending a year in a shutdown robs an American of a year out of the 80 years that he can be expected to live. This is a 1/80=%1.25 mortality rate, which the society pays in exchange for averting the 1% mortality rate from coronavirus.

It is hard to believe that individuals would be willing to stop the world and get off in order to avert a 1% death rate. Individuals naturally engage in risky activities such as driving, working (and suffering on-the-job accidents), and, more importantly, breathing. Allegedly, 200,000 Americans die from pollution every year. Halting an economy for a year would save all those people. Stopping the economy for 15 years would be even better, and save all the lives that coronavirus would take. Indeed, stopping the economy is a gift that keeps giving, every year, while coronavirus deaths can be averted only once. Yet, with the exception of some climate change fundamentalists, there were no calls for stopping the economy before the pandemic.

The economy shutdown due to coronavirus seems to be motivated by the same lack of faith in progress and society’s ability to mobilise to find technological solutions (if not for this strain of the virus then for the future ones), and by the Catholic belief in the virtue of self-flagellation of the kind sported by climate-change fundamentalists of Greta’s persuasion. This lack of faith is not wholly the responsibility of governments and is shared by the citizens.