I am delighted to announce that the 10th edition of my textbook, Price Theory and Applications, is now available wherever good books are sold. There’s also a free sample chapter.

Here’s what’s special about this edition:

- I started out by rereading large parts of the past several editions, from which I learned that not every change was an improvement. Some things were a lot clearer in edition 7 than in edition 9. (And sometimes vice-versa of course.) I worked hard to make sure that in the tenth edition, every section and subsection would be the best it could be — which sometimes meant resurrecting an old version, or, more often, combining the best of the old and the new.

- In the past, I’ve tried to keep all of the end-of-chapter problem sets to about the same length, which sometimes meant omitting some really great problems. This time, I decided that was stupid. Whenever I had 40 or 50 really good problems, I included them all.

- This edition benefited from the extraordinary talents, wisdom and persistence of the extraordinary Lisa Talpey, who read every draft, called out everything that seemed even slightly unclear, gave me a chance to rewrite, then read it all again, equally carefully, and took me through as many rounds of this as necessary until everything made sense to her. She also caught pretty much all the typos. I am sure that thanks to Lisa, this edition is far friendlier to the reader than any of those that came before.

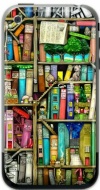

- For the first time, I designed my own cover! How do you like it?

The publisher’s webpage, and information on ordering for your classes, is here.