In yesterday’s post about Eric Garner, I wrote:

Suppose you are a typical street vendor of an illegal product, such as, oh, say, untaxed cigarettes.

Suppose the police make a habit of harassing such vendors, by confiscating their products, smacking them around, hauling them off to jail, and perhaps occasionally killing a few.

I have good news: The police can’t hurt you.

…

Here’s why: Street vending can never be substantially more rewarding than, say, carwashing. If it were, car washers would become street vendors, driving down profits until the rewards are equalized. If car washers were happier than street vendors, we’d see the same process in reverse. (The key observation here is that it’s very easy to move back and forth between street vending and other occupations that require little in the way of special training or special skills.)

Because police harassment of street vendors has no effect on the happiness of car washers, and because street vendors are always just as happy as car washers, it follows that police harassment has no effect on the happiness of street vendors.

…

So if you’re a street vendor, the police can’t hurt you. On the other hand, when the police go around putting people in deadly chokeholds, they’re clearly hurting someone. So the question is: Who?

Answer: Not the vendors, but their customers. Fewer vendors means higher prices. That hurts consumers, and the sum total of that harm adds up to the harm that we see in the viral videos.

Several commenters jumped in to question the claims that:

- If you’re a street vendor, the police can’t hurt you.

- The costs of police harassment ultimately fall on consumers.

I’d like to thank those commenters — particularly David Sloan, Keshav Srinivasan and Eric — for keeping me honest and for persisting when I was initially too quick to dismiss their questions.

With regard to the first point, what I actually should have said was:

- If you’re a street vendor, the police can’t hurt you more than an eentsy weentsy bit.

That’s because harassment causes street vendors to move into a great many other occupations, one of which is car washing. For every displaced street vendor we get, say, 1/2000 of an extra car washer — bringing wages ever so slightly down in the car washing industry and therefore making both car washers and street vendors ever so slightly worse off.

I do not consider this a significant correction.

With regard to the second point, it would have been more accurate to say this:

- The greater the harassment, the more of its burden falls on consumers in the harassed industry.

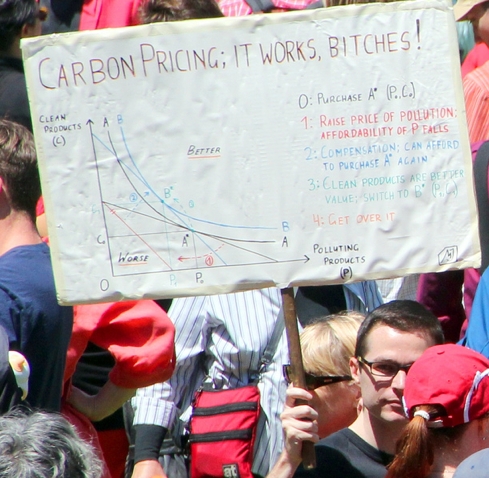

More precisely, if we consider the harassment equivalent to a tax of T, then the burden on producers tends to grow linearly in T while the burden on consumers in the harassed industry tends to grow quadratically in T.

However, here are two points I now realize I’d overlooked:

- The linear/quadratic thing is at least partially misleading, because there is a limit on how big T can be — if T grows beyond a certain point, then the first industry disappears entirely. So we’re not looking at arbitrarily large T’s here, making “growth rates for large T” less relevant. Thus workers collectively can in fact — and in contrast to what I said yesterday — bear a substantial burden of the cost.

- While consumer surplus in the first industry shrinks quadratically in T, consumer surplus in the other industries grows quadratically in T, and in fact, the total consumer surplus across all industries can increase as a result of the street harassment. Thus it’s possible for workers to bear more than the entire burden of the harassment!

Here’s an explicit model:

Continue reading ‘Corrections’