Under quite general conditions, free trade pacts lead to higher average real incomes in every participating country. The argument for this proposition is simple, incontrovertible, and entirely non-controversial among those who have taken a few minutes to understand it. This stands in contrast to the arguments for, say, Darwinian evolution or anthropogenic climate change, which rely on vast bodies of evidence that most of us will never digest. Your opinions on evolution and climate change almost surely rely at least in part on the testimony of experts. Free trade is different. It doesn’t matter what the experts say, because you can check each step in the argument for yourself.

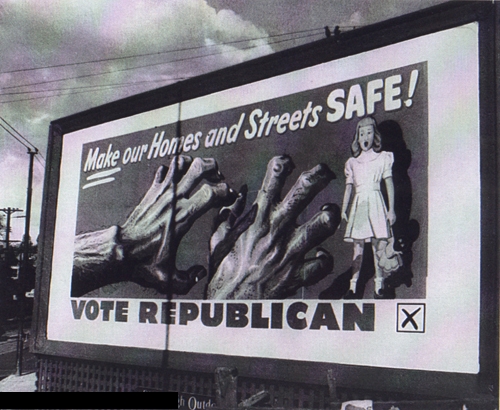

Educated people know this. So when they want to throw up roadblocks in the way of free trade, they don’t say silly and obviously false things like “free trade will make us poorer”. Instead, they say silly things like “Sure, free trade will make us better off on average. But there are still both losers and winners!” From this, they want us to conclude either that free trade is not a good thing, or that at the very least, the winners should compensate the losers.

This strikes me as an extraordinarily dishonest way of arguing, because pretty much nobody ever argues this way about anything else, even though every policy change in history has created both winners and losers. In fact, every human action has both winners and losers. When Archie takes Betty instead of Veronica to the ice cream shoppe instead of the movies, both Veronica and the theater owner lose out. It does not follow that all human actions are wrong, or immoral, or should be discouraged by law, and it does not follow that all human actions should be followed by compensation to the losers. What, then, is so special about free trade?

The problem is confounded by the fact that with free trade, unlike many other policies, the winners are often poorer than the losers. When Americans lose their $30 an hour jobs making air conditioners so that they can be made by $20-an-hour foreigners, the big losers are Americans whose wages fall from $30 to $20. The big winners are Americans who can now for the first time afford air conditioning. Most of those people are probably making less than $20 an hour. (On this point, see also here.)

For those who insist on repeating the old “What about the losers?” refrain, I’ve prepeared a little quiz to test your moral consistency:

- In 1998, a new grocery store opened in my neighborhood, offering better food at lower prices than the old grocery store. This is generally perceived to have been a good thing overall, but at same time it was bad for the owners of the existing grocery store.

- Does this mean that the new grocery store should have been prohibited from opening?

- Does this mean that the winners — i.e. my neighbors and I — should have compensated the losers — i.e. the proprietors of the old grocery store — for their losses?

- In 2005, I stopped going to the barber and started cutting my own hair. My friends think my hair looks better now, and there’s a general perception that the change has been a good thing overall.

- Does this mean that I should be required to return to my barber?

- Does this mean that the winners — i.e. my friends and I — should have compensated the loser — i.e. my ex-barber — for her losses?

- In 2008, Google introduced the Android operating system to compete with Apple’s iPhone monopoly. This is generally perceived to have been a good thing overall, but at the same time it was bad for Apple’s shareholders.

- Does this mean that Google should have been prohibited from developing the Android system?

- Does this mean that the winners — i.e. everyone who purchased an Android, and everyone who got his iPhone a little cheaper thanks to the competition — should have compensated Apple’s shareholders for their losses?

- In 1863, Abraham Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation, ending slavery in the United States of America. This is generally perceived to have been a good thing overall, but at the same time it was bad for slaveholders.

- Does this mean that Lincoln should not have freed the slaves?

- Does this mean that the winners — i.e. the freed slaves — should have compensated the losers — i.e. the slaveholders — for their losses?

- In 2008, Bernard Madoff was arrested and his ongoing Ponzi scheme was cut short. This is generally perceived to have been a good thing overall, but at the same time it was bad for Bernie Madoff.

- Does this mean that Madoff should not have been arrested?

- Does this mean that the winners — i.e. the Madoff victims — should have compensated the losers — i.e. Madoff and his co-conspirators — for their losses?

Scoring: If your answers were mostly “no”, and if you are nevertheless skeptical of free trade pacts, you’ve got some explaining to do.

Continue reading ‘Trading in Fallacies’