Imagine you’ve got a drinking problem. And imagine this conversation with your spouse:

Spouse: Dear, you’ve really got to do something about your drinking. You’ve been in three auto accidents this week, you’ve lost your job, and you’ve been trying to beat the children, though you keep passing out before you can get to them. I want to help you figure out how to get this under control.

You: You’ve got a fair point there. But let me point out that it would also be a good idea to redecorate the living room.

Spouse: Well, maybe so, and it’s something we can talk about at some point. But right now, I’d really like to focus on the drinking issue.

You: Doesn’t that strike you as imbalanced? Here we’ve got two issues on the table, and you want to focus 100% on one of them and 0% on the other. Why are you being so one-sided?

Spouse: Well, but I feel like there’s some urgency about the drinking thing, and I’d like to prioritize it.

You: Apparently, you’re fanatical on this issue. I don’t see how I can continue to take you seriously.

Spouse: Well, actually I’m trying to get you to focus on a very serious issue.

You: Yes, but by focusing exclusively on that issue, you’re betraying your fanaticism. Clearly, I’m the one who’s willing to address our problems, and you’re the one who’s just out to score debating points.

Spouse: Huh?

You: Not only that, but I’ve got a Nobel-prize winning economist who agrees with me!

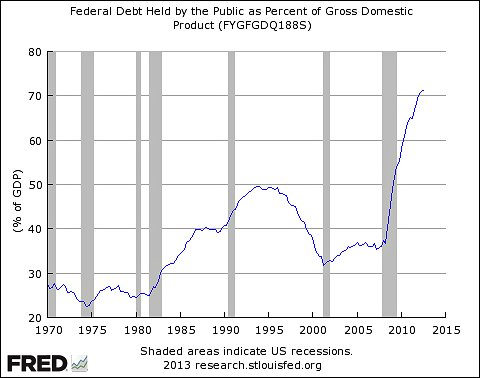

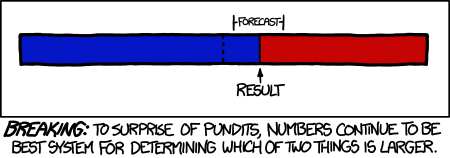

How does that make you feel? I feel that way a lot when I read the news lately. Arguably, our country faces a spending crisis. The Republicans claim they want to deal with that crisis. (There’s some legitimate question about how sincere they are, but they at least say they want to deal with it.) The Democrats say: Okay, but let’s also talk about raising taxes. Maybe they’d also like to talk about redecorating the Rotunda; this seems roughly as pertinent. In other words, the Democrats attempt to deflect attention from the crisis (or the alleged crisis) by insisting that we talk about some other thing at the same time — and then they insist that the Republicans, by insisting that we focus on the issue at hand, are “betraying their fanaticism”. And they’ve managed to find a Nobel-prize winning economist willing to parrot this nonsense almost daily on the pages and webpages of the New York Times.