The Internet seems to have bred a peculiar subspecies of troll that cheerfully devotes enormous effort to refuting arguments nobody ever made. While they seem to have infinite time to construct these pointless rebuttals, these troll-types seem to have no time at all in which to actually digest the arguments they think they’re rebutting. They start with a guess as to what someone else might have said, and seem all but incapable of entertaining the notion that they might have guessed wrong. Is there a name for these people? “Crank” and “troll” are too general. If it were up to me, we’d reserve the word “Bozo” for this purpose, but it too is already in more general use. We need a new word! Give me your suggestions!

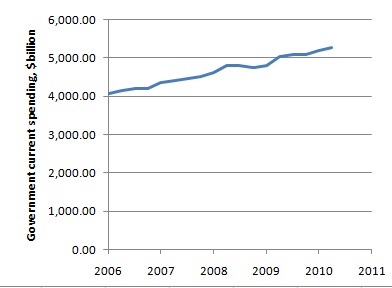

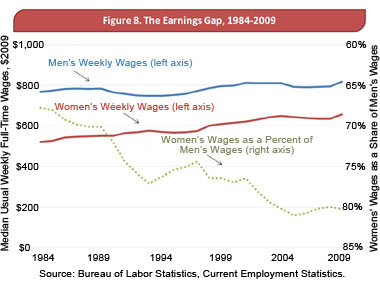

A title like More Sex is Safer Sex is like red meat to these folks and on Monday we took a moment to defend that argument against the latest Bozo Barrage (I’ll stick with this name till you give me a better one). Then on Tuesday we confronted a different subspecies of troll — the statistical obfuscator. Our reader Windypundit did some detective work and discovered that the offending graph was produced by an agency of the United States government. That, of course, is no excuse for perpetrating the deception.

Our graphical escapade led to a discussion of the gender gap in wages and whether it can be plausibly explained by employer discrimination. It’s often argued that it can’t, because that would require employers to sacrifice a profit opportunity. On Wednesday, I rejected that argument on the grounds that employers sacrifice profit opportunities all the time — but offered a (slightly) more sophisticated version that rejects the employer-discrimination hypothesis because it would require employers to sacrifice a very large profit opportunity. Of course, as our reader Patrick observes, this still doesn’t rule out the hypotheses of customer-discrimination or employee-discrimination. (In the latter case, male workers refuse to accept female colleagues. And again, the argument I gave can’t reject this. On the other hand, a different argument probably can — if the wage gap were driven by employee-discrimination, firms could profit not by hiring a few more females, but by hiring only females. In equilibrium, you’d expect half of all firms to be all female, half all male, and wages to be equalized across firms.

Thursday I reran a year-old post on how to add all the positive integers and get -1/12. This post generated just one comment! I’m not sure whether this was because none of you like this kind of thing, or whether you found it too awesome to remark on.

Continue reading ‘Weekend Roundup’