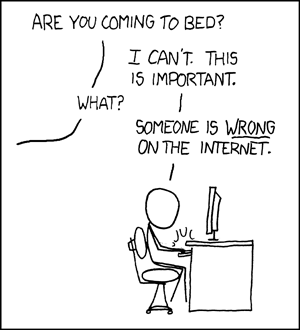

How rational are you? I once posted a test, based on ideas of the economist Maurice Allais, that most people seem to fail. Today’s test, based on ideas of the economist Dick Zeckhauser and the philosopher Richard Jeffrey, is one that almost everyone fails.

How rational are you? I once posted a test, based on ideas of the economist Maurice Allais, that most people seem to fail. Today’s test, based on ideas of the economist Dick Zeckhauser and the philosopher Richard Jeffrey, is one that almost everyone fails.

Suppose you’ve somehow found yourself in a game of Russian Roulette. Russian roulette is not, perhaps, the most rational of games to be playing in the first place, so let’s suppose you’ve been forced to play.

Question 1: At the moment, there are two bullets in the six-shooter pointed at your head. How much would you pay to remove both bullets and play with an empty chamber?

Question 2: At the moment, there are four bullets in the six-shooter. How much would you pay to remove one of them and play with a half-full chamber?

In case it’s hard for you to come up with specific numbers, let’s ask a simpler question:

The Big Question: Which would you pay more for — the right to remove two bullets out of two, or the right to remove one bullet out of four?

The question is to be answered on the assumption that you have no heirs you care about, so money has no value to you after you’re dead.

Almost everybody says they’d pay more in the first case than the second. Arguably, that means that in this scenario almost nobody is rational — because a rational person would give the same answer to both questions.

The reason for that is not immediately obvious. To understand it, you’ve got to think about four questions:

Continue reading ‘Another Rationality Test’

One of Paul Krugman’s favorite stories is about the baby-sitting co-op that almost collapsed when members started hoarding scrip; similarly, he says, a lot of economic activity can dry up when people start hoarding money. Last Tuesday, in a post called

One of Paul Krugman’s favorite stories is about the baby-sitting co-op that almost collapsed when members started hoarding scrip; similarly, he says, a lot of economic activity can dry up when people start hoarding money. Last Tuesday, in a post called