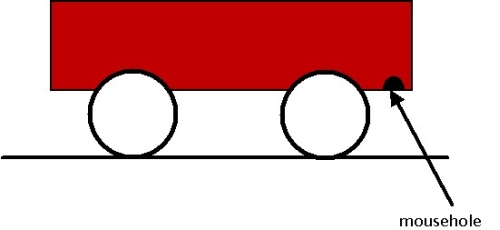

Yesterday’s puzzle was this: A boxcar filled with water sits on a frictionless train track. A mouse gnaws a small hole in the bottom of the boxcar, near what we’ll call the right-hand end. What happens to the boxcar?

(Spoiler warning!)

Yesterday’s puzzle was this: A boxcar filled with water sits on a frictionless train track. A mouse gnaws a small hole in the bottom of the boxcar, near what we’ll call the right-hand end. What happens to the boxcar?

(Spoiler warning!)

I’ve just been pointed to this notice of a conference in honor of the topologist Tom Goodwillie‘s 60th birthday.

This reminded me of several things, not all of them related to the relentless march of time.

For example, once a very long time ago (though it sure doesn’t seem that way) Tom asked me a simple physics question that troubled me far more than I now think it ought to have:

A boxcar full of water sits on a frictionless train track. A mouse gnaws a hole through the bottom of the boxcar, in the location indicated here:

The water, of course, comes gushing out. What happens to the boxcar?

Big news from the math world:

One of the oldest problems in number theory is the twin primes problem: Are there or are there not infinitely many ways to write the number 2 as a difference of two primes? You can, for example, write 2 = 5 -3, or 2 = 7 – 5, or 2 = 13 – 11. Does or does not this list go on forever? There are very strong reasons to believe the answer is yes, but many a great mathematician has tried and failed to find a proof.

Here’s a related problem: Are there or are there not infinitely many ways to write the number 4 as a difference of two primes? What about the number 6? Or 8? Or any even number you care to think about? It seems likely that the answer is yes in every case, though no proof is known in any case. But….

This might be one of those questions I’ll eventually be embarrassed for asking, but…..

This might be one of those questions I’ll eventually be embarrassed for asking, but…..

Imagine a future in which Bitcoins (or some other non-governmental currency) are widely accepted and easily substitutable for dollars, at an exchange rate of (say) $X per Bitcoin.

Then if there are M dollars and B bitcoins in circulation, the money supply (measured in dollars) is effectively M + X B .

Money demand is presumably P D, where P is the general price level and D depends on things like the volume of transactions and the payment habits of the community. (If it helps, we can write D = T/V where T is the volume of transactions and V is the velocity of money.)

Equilibrium in the money market requires that supply equals demand, so

Now M is determined by the monetary authorities; B is determined by the Bitcoin algorithm, and D, as noted above, is determined outside the money market.

That leaves me with two variables (X and P) but only one equation. What pins down the values of these variables?

When you met the late Armen Alchian on the street, he used to greet you not with “Hello” or “How ya doin’?”, but with “What did you learn today?” Today I learned that there are contexts in which the most ludicrous reasoning is guaranteed to lead you to a correct conclusion. This is too cool not to share.

But first a little context. The first part is a little less cool, but it’s still fun and it will only take a minute.

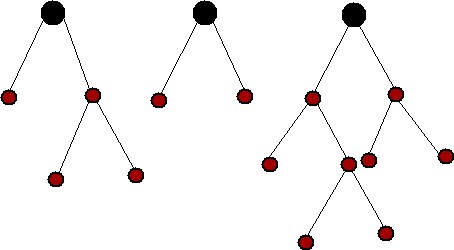

First, I have to tell you what a tree is. A tree is something that has a root, and then either zero or two branches growing out of that root, and then either zero or two branches (a “left branch” and a “right branch”) growing out of each branch end, and then either zero or two branches growing out of each of those branch ends, and so on. Here are some trees. (The little red dots are the branch ends and the big black dot is the root; these trees grow upside down.)

A pair of trees is, as you might guess, two trees — a first and a second.

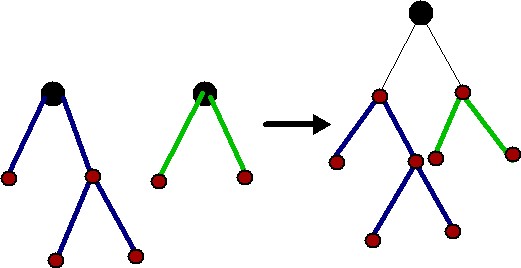

There are infinitely many trees, and infinitely many pairs of trees, and purely abstract considerations tell us that there’s got to be a one-one correspondence between these two infinities. But what if we ask for a simple, easily describable one-one correspondence? Well, here’s an attempt: Starting with a pair of trees, you can create a single tree by creating a root with two branches, and then sticking the two trees from the pair onto the ends of the two branches. Like so:

Sorry to have been so silent this week; various deadlines have kept me away from this corner of the Internet. I’ll be back in force next week for sure. Meanwhile, if you’re looking for some good reading, this is the best thing I’ve seen all morning.

Edited to add: “Best all morning” was not intended as damning-by-faint-praise. It’s actually the best of many mornings.

|

|

|

|

|

|

You and a stranger have been instructed to meet up sometime tomorrow, somewhere in New York City. You (and the stranger) can decide for yourselves when and where to look for each other. But there can be no advance communication. Where do you go?

Me, I’d be at the front entrance to the Empire State Building at noon, possibly missing my counterpart, who might be under the clock at Grand Central Station. But, because there are only a small number of points in New York City that stand out as “extra-special”, we’ve at least got a chance to find each other.

A Schelling point is something that stands out from the background so sharply that we can expect people to coordinate around it. Schelling points are on my mind this week, because I’ve just heard David Friedman give a fascinating talk about the evolution of property rights, and Schelling points play a big role in his story. But that story is not the topic of this post.

Instead, I’m curious about the Schelling points that say, two mathematicians, or two economists, or two philosophers, or two poets, or two street hustlers might converge on. Suppose, for example, that you asked two mathematicians each to separately pick a number between 200 and 300, with a prize if their answers coincide. I’m guessing they both go for 256, the only power of two within range.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Last week was not the first time the United States was transfixed by an act of terror. In 1964, three civil rights workers in Philadelphia, Mississippi were (quoting Wikipedia) “threatened, intimidated, beaten, shot, and buried by members of the Mississippi White Knights of the Ku Klux Klan, the Neshoba County Sheriff’s Office and the Philadelphia Police Department.” It took 44 days and an FBI-initiated act of torture to locate their bodies.

The FBI, in a nod to the theory of comparative advantage, subcontracted the torture to the Mafia, more specifically to the Colombo family associate Gregory Scarpa. Here’s the story as relayed by Selwyn Raab, the New York Times investigative reporter who covered the Mafia for 25 years:

[Scarpa] went down to Mississippi for the FBI and kidnapped a KKK guy agents were sure was involved in disposing of the bodies. The guy had an appliance store. Scarpa bought a TV and came back to the store to pick it up just as he was closing. The guy helps him carry the TV to his car parked in the back of the store. Scarpa knocks him out with a bop to the head, takes him off to the woods, beats him up, sticks a gun down his throat and says “I’m going to blow your head off”. The KKK guy realized he was Mafia and wasn’t kidding and told him where to look for the bodies.

(Source: Raab’s book Five Families, which is fascinating throughout. Raab says the story has been verified by “former law enforcement officials who asked for anonymity and lawyers who are aware of the circumstances”.)

The moral of the story is that torture sometimes works. Other times it doesn’t, eliciting either no information, or false information, or whatever “information” the victim believes the inquisitor wants to hear. I am almost 100% ignorant, and hence virtually 100% agnostic, about the relative frequency of these outcomes in those cases where the torturer is both skilled in his art and genuinely interested in eliciting the truth. I will be very glad if any educated reader can shed light on this question. I doubt that we’re likely to learn of any controlled experiments, but I’ll settle for sketchy data or even well-chosen anecdotes. Failing that, I’ll settle for plausibility arguments.

Since we’ve been talking about dogs and cats this week:

Hat tip to my sister Barbara.

These were the posted prices at my local gas station this morning:

(Note the 5 cent discount for cash on regular and premium, as opposed to the 65 cent (!!!) discount on plus.) Unless this was just a mistake, my complete inability to explain it makes me question whether I should be allowed to teach economics.

The solution to yesterday’s rationality test:

This one is much much simpler (and much less infuriating) than some of our earlier rationality puzzles (e.g. here and especially here), but it has a good pedigree, having come to me from my student Tallis Moore, who found it in a paper of Armen Alchian, who attibutes it to the Nobel prizewinner Harry Markowitz.

Several commenters got it exactly right, but whenever possible, I prefer an explanation that invokes cats and dogs. So: Suppose I give you a choice between A) a cat, B) a dog, and C) a coin flip to determine which pet you’ll get:

|

|

|

It’s perfectly rational to prefer the cat to the dog, and perfectly rational to prefer the dog to the cat, but (according to the traditional definition of rationality) quite indefensible to prefer the coin flip to either.

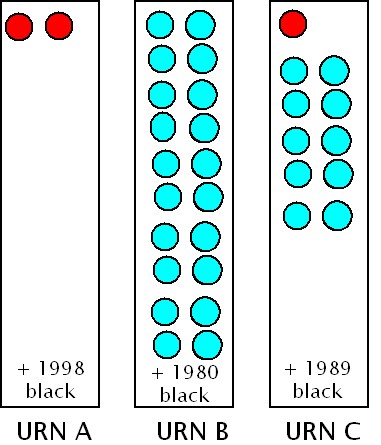

In front of you lie three urns, labeled A, B and C. Each contains 2000 balls. Urn A has 2 reds and the rest black; Urn B has 20 blue and the rest black; Urn C contains 1 red, 10 blue and the rest black. Like so:

You can reach into the urn of your choice and remove a ball. If you draw red, you get $1000; if you draw blue, you get $100; if you draw black, you get nothing. Which urn do you pick and why?

According to the New York Post, “President Obama’s temporary-amnesty program has paid off for 454,000 young immigrants who were brought here illegally.”

That’s all well and good, and I don’t begrudge a single one of those young immigrants his or her good fortune. But let’s be clear here: The biggest losers from our country’s heartless immigration policies are not the young people who have managed to find their way here only to risk deportation. The biggest losers are those who never got here in the first place.

If it were my job to remedy the evils of American immigration policy, I’d start by making it easier to get here, not easier to stay here. Or to put this another way: If the President is willing to allow 454,000 young immigrants (and no more) to be here, I’d prefer he deport everyone who’s already here and bring in another 454,000 to replace them. That way, a million people get at least some opportunity to reap the (relative) benefits of American education and American freedom, as opposed to a lucky half-million reaping all the benefits while another half-million get nothing.

It would be better, of course, to welcome everyone.

Four terrific posts by David Friedman, partly on psychic harm, partly on talking about psychic harm. I’d recommend these highly even if they hadn’t invoked my name.

Landsburg v Bork: What Counts As Injury?

Response to Bork and Landsburg

Why Landsburg’s Puzzle is Interesting

Why do senior citizens get so many discounts? A lot of it is because they have the time to shop for bargains — so if you don’t give them a bargain, they’ll find someone else who will.

We talked about this and other forms of discounting (or, in economic jargon, “price discrimination”) in my Principles class just last week, emphasizing that it does no good to hand out discounts willy-nilly; instead you want to target them to the most price sensitive customers. That’s why you sometimes have to jump through hoops (like filling out a rebate form) to get your discount — the customers who are motivated to fill out a rebate form tend to be exactly the same customers who are most likely to look elsewhere for a good price.

We talked too about how the airlines have always strived to separate business travelers from leisure travelers so they can charge the business travelers more and the leisure travelers less — the leisure travelers being more likely to take the train (or just stay home) if they don’t get a bargain. The problem, though, is that it’s hard to tell who’s a business traveler and who’s a leisure traveler. So historically, there have been devices like discounts for those who stay over a Saturday night, which is something a business traveler is unlikely to want to do.

Now I can go back to my students and tell them something about the value of staying awake in their economics classes. Because someone who’d obviously absorbed this lesson well has started a new site called GetGoing that takes this idea and runs with it. Here’s how it works: You book two conflicting itineraries, say a trip to San Francisco and a trip to Atlanta on the same date. You are quoted prices that are typically about half what you’d get elsewhere. You agree to fly. And then it books one of the trips, chosen randomly.

Note added on 4/5: Readers who want the short version can skip down to where it says “Edited to Add”.

I’m somewhat hesitant to post this, since I believe my regular readers will find it all to be entirely obvious and hence entirely unnecessary. But we’ve had more than the usual number of non-regular readers here the past few days, largely in response to my post on psychic harm, and more than a few of them have made the mistake of plunging into a conversation they didn’t understand (often, apparently, without even reading the post they were responding to). Per my usual policy in long threads, I’ve deleted comments that failed to advance the discussion, either because they were off topic or did no more than repeat things that had already been said. In most, but not all, such cases, I drop short notes to the commenters, explaining why their posts were deleted and inviting them to come back with something more germane. Often (and this week has been no exception), I get notes back from these people saying they’ve learned something, which is gratifying enough that I keep on sending those explanatory notes. (If your post was deleted and you didn’t get a note, you probably just had the bad luck to post at a time when I was unusually busy or distracted.) But since certain points come up repeatedly, it might be more efficient to mention them here.

1. This was not a post about censorship, or about the environment, or about rape. It was a post about where to draw lines between purely psychic harm that should receive policy weight and purely psychic harm that shouldn’t. This is an issue I raise from time to time, because I find it both perplexing and important. And it interacts with lot of other standard issues in public policy in ways that make it impossible (for those of us who care about such things) to ignore.

2. The post was laden with unrealistic hypotheticals. That’s the only way I know of to approach these questions. Take rape, for example. Rape frequently has ghastly physical and psychological consequences for the victim. We all know that, which is precisely why it’s important (in this kind of discussion) to assume those consequences away. The whole point is to focus on the stuff we’re not sure of, such as: Should my distress over someone else‘s rape receive policy weight? To focus on that question, it helps to imagine a scenario where that’s the only distress. In other words, we assume away all the usual harm to the victim precisely because we’re already know that this harm is dreadful and merits policy weight. To focus on examples where the victim sustains damage would be to say, in effect, that we’re not sure how to feel about that damage. (Otherwise, why investigate those examples?)

Or to put this yet another way: In this business, the way one acknowledges that an issue is settled is to assume it away. It is settled that damage to rape victims is real, great, important, and deserves the attention of the law. Thus we assume it away.

Edited to add: Two extremely thoughtful commenters have pointed out that the first post dealt both with psychic harm to the victim and with psychic harm to the general public, and that these are two different issues. Indeed they are, but both are difficult in the same way, and both of them are clarified by hypothetical examples.

Economists often say that the law should be written to promote efficient outcomes. That’s more ambiguous than it sounds.

Suppose I want to take an action that causes you harm; for example, I want to cut down a tree that you like looking at. How do we tell if that action is efficient?

Definition 1. The action is efficient if my willingness to pay exceeds your willingness to accept. For example, if I’m willing to pay $100 for the privilege of harvesting the tree, and if you’d accept less than $100 to part with it, then the tree-cutting is efficient.

Definition 2. The tree-cutting is efficient if it would occur in a world with no transactions costs (i.e. a world in which there are no impediments to bargaining).

In many circumstances, these definitions are equivalent, and economists often pretend they’re equivalent always — but sometimes they’re not.

Example 1. I want to punch you in the nose non-consensually. (The non-consensuality is a big part of my enjoyment.) I’d pay $100 to punch you in the nose, and you’d accept $50 to take the punch. By Definition 1, the punch is efficient. But the punch would be unlikely to occur in a world with no transactions costs, because it would require bargaining, hence consensuality on your part, which kills my interest. So by Definition 2, the punch is inefficient.

Example 2. I am willing to pay $100 to cut down a tree; you are willing to accept no less than $150 to part with it. By Definition 1, the cutting is inefficient. But part of the reason I’m willing to pay only $100 is that I’m credit constrained. In a world with no transactions costs, I’d borrow more, and would be willing to pay $200 to cut down the tree. So by Definition 2, the cutting is efficient.

Example 3. I am willing to pay $1000 to cut down a tree; you are willing to accept $500 to part with it. By Definition 1, the cutting is efficient. But the only reason I’m willing to pay so much is that I make an excellent living in my job as a mediator who helps people overcome transactions costs. In a world with no transactions costs, I’d be much poorer and would be willing to pay only $200 to cut the tree. So by Definition 2, the cutting is inefficient.

Having just discovered a staggering $910 (!!!!) in unexplained and unauthorized charges to my MasterCard by the Wall Street Journal (no, these were not legit renewal fees), I have just spent what seems like the better part of four days telling my story on the phone to one customer service rep after another, each of whom has found a new way to lie to me. (“We’ll call you back by the end of the day” was the most frequent lie, followed by “we’re putting through a half-refund now and someone with higher authority will call you shortly to arrange the rest” — which turned out to be two lies in one). Finally, I decided to send an email with the whole sad story, asking for a refund and mentioning that I sure hope there won’t be any resulting confusion that interrupts my delivery service. I got an email back saying “Per your request, we’re cancelling your delivery service”. Today I had no newspaper — and still no refund.

Having just discovered a staggering $910 (!!!!) in unexplained and unauthorized charges to my MasterCard by the Wall Street Journal (no, these were not legit renewal fees), I have just spent what seems like the better part of four days telling my story on the phone to one customer service rep after another, each of whom has found a new way to lie to me. (“We’ll call you back by the end of the day” was the most frequent lie, followed by “we’re putting through a half-refund now and someone with higher authority will call you shortly to arrange the rest” — which turned out to be two lies in one). Finally, I decided to send an email with the whole sad story, asking for a refund and mentioning that I sure hope there won’t be any resulting confusion that interrupts my delivery service. I got an email back saying “Per your request, we’re cancelling your delivery service”. Today I had no newspaper — and still no refund.

Think of the top three worst customer service stories you’ve ever heard. Chances are excellent that versions of all three have cropped up along the way in this sordid saga, the details of which I will suppress because I’m sure they’re less interesting to you than they are to me.

But I will mention this: Aside from the lying, and the lying and the lying, there’s also the fact that absolutely nobody appears to keep any record of these conversations, so that each time I call, I’m starting from scratch, explaining the whole story to a customer service rep who won’t put me through to a supervisor until I rehash the whole thing, then waiting on hold ten minutes for said supervisor, who needs the entire story told from scratch again before connecting me to the department that’s really equipped to deal with this, where I wait on hold for another ten minutes before telling my story yet again and, 50% of the time, getting disconnected. When I call back, it’s back to Square One.

Oh, yes….and they’ve also studiously ignored my repeated requests/demands that they expunge my credit card number from their records, and refused to acknowledge my repeated notifications that they do not have my authorization to charge my credit card for anything ever again.

Continue reading ‘Never Give Your Credit Card to the Wall Street Journal’

The one lesson I most want my students to learn is this: You can’t just say anything. It’s important to care about making sense. So I find it particularly galling when people violate this rule while presenting themselves to the public as economists. It undercuts the single most important lesson we have to teach.

THe latest culprit is the unchastened serial offender Robert Frank, writing in the Business section of the Sunday New York Times. His argument has two parts, one philosophical and one economic. In both cases he substitutes blather for analysis. I’m less concerned about the philosophical part, because it’s such obvious nonsense that I can’t imagine anyone will take it seriously. But the fact that he got the economics wrong, and more importantly, his implied message that it doesn’t matter whether you get the economics wrong, seems calculated to undermine the public’s faith in economists. That’s the part I take personally.

Frank’s subject this time is New York Mayor Bloomberg’s failed attempt to curb the sale of large sugary drinks. While acknowledging that such a ban would curb individual freedom in some dimensions, Frank argues that it would simultaneously enhance individual freedom in others — namely, it would enhance your “freedom” to prevent your child from drinking lots of soda.

Now, I do not doubt that for some parents, a ban on large sugary drinks would make it easier to prevent children from drinking lots of soda, but to call this an enhancement of freedom, you (or Robert Frank) would have to use the word “freedom” in a very unorthodox way. By Frank’s definition, a ban on Democratic campaign ads would enhance your “freedom” to prevent your children from voting for Democrats. Would Frank endorse such terminology? Or suggest that this effect, in and of itself, might suffice to consider the advertising ban a generally pro-freedom initiative?

A while back, I posted a link to the first of my four talks at the 2012 Cato University. Today, I’m posting the second talk, titled “How Markets Work”, with the others to appear eventually.

Incidentally, I won’t be at the 2013 Cato U, but other stellar speakers will be. This really is an extraordinarily well run event, and I’ve met many fascinating people every time I’ve been there. It’s not too late to register!

Flightstats.com is a website that reports the on-time performance of individual airline flights. If you look up, oh, say, USAirways Flight 464, you’ll find this assessment:

Now the puzzle: How, exactly, does one go about controlling for standard deviation and mean?

Hat tip to Michael Lugo at God Plays Dice

Note added on 4/5: Some readers missed the point of this post very badly, which means that it could have been written more clearly. Here is a brief attempt to clarify.

______________________________________-

Here are three dilemmas about public policy:

Farnsworth McCrankypants just hates the idea that someone, somewhere might be looking at pornography. It’s not that he thinks porn causes bad behavior; it’s just the idea of other people’s viewing habits that causes him deep psychic distress. Ought Farnsworth’s preferences be weighed in the balance when we make public policy? In other words, is the psychic harm to Farnsworth an argument for discouraging pornography through, say, taxation or regulation?

Granola McMustardseed just hates the idea that someone, somewhere might be altering the natural state of a wilderness area. It’s not that Granola ever plans to visit that area or to derive any other direct benefits from it; it’s just the idea of wilderness desecration that causes her deep psychic distress. Ought Granola’s preferences be weighed in the balance when we make public policy? In other words, is the psychic harm to Granola an argument for discouraging, say, oil drilling in Alaska, either through taxes or regulation?

Let’s suppose that you, or I, or someone we love, or someone we care about from afar, is raped while unconscious in a way that causes no direct physical harm — no injury, no pregnancy, no disease transmission. (Note: The Steubenville rape victim, according to all the accounts I’ve read, was not even aware that she’d been sexually assaulted until she learned about it from the Internet some days later.) Despite the lack of physical damage, we are shocked, appalled and horrified at the thought of being treated in this way, and suffer deep trauma as a result. Ought the law discourage such acts of rape? Should they be illegal?

If your answers to questions 1, 2 and 3 were not all identical, what is the key difference among them?

Continue reading ‘Censorship, Environmentalism and Steubenville’

|

|

Benjamin Franklin was against smallpox vaccination — until his own unvaccinated son died of smallpox, whereupon Franklin changed sides and began urging other parents to vaccinate their children.

This has always struck me as a bit of a black mark against Franklin’s rationality. He’d always known that smallpox kills; he’d always known that vaccinations (at least in the early 18th century) could also kill. As a parent, he’d weighed one risk against the other and used his best judgment about where to place his bets. In a world where smallpox deaths were commonplace, his own son’s death was just one more virtually insignificant data point. Could inoculation have been an unacceptable risk against a disease that killed 100,000 people a year, but a prudent precaution against a disease that killed 100,001?

That’s how I feel, too, about Senator Rob Portman’s turnabout on the issue of gay marriage after learning that his son is gay. Continue reading ‘History Repeats Itself’

By the standards of history, you, I, and (unless you’re a very atypical blog reader) pretty much everyone we’ve ever met is fabulously wealthy. How wealthy? One good measure is our ability and willingness to support the frivolity of others. Here are two recent technological innovations that give eloquent testimony to just how well off we are.

First, the Oreo separating machine. (Yes, I realize that every other blogger on earth has already linked to this one, but if you haven’t actually watched it yet, you really should click through):

And then….

If I could choose any name I wanted and require everyone to call me by that name, I think I would probably go with something considerably more creative than “Francis”. Just saying.

I am not one of the public intellectuals who were queried by The Atlantic (link might require subscription) as to which date most changed world history — but on the Internet, you can always spout off without an invitation.

I am not one of the public intellectuals who were queried by The Atlantic (link might require subscription) as to which date most changed world history — but on the Internet, you can always spout off without an invitation.

It’s hard to argue with Freeman Dyson, who nominates the day an asteroid wiped out the dinosaurs, clearing the evolutionary path for the likes of you and me.

(Actually, it’s remarkably easy to argue with Freeman Dyson. I know this, having done so over tea in Princeton, many years ago. He made it very easy indeed, despite (or perhaps because of) the fact that he was 100% right and I was 100% wrong.)

At the opposite end of the intellectual spectrum, the standup comedian W. Kamau Bell, after lamenting that there’s no way he can get this right so he might as well punt, nominates the day Michael Jackson first performed the moonwalk on national TV. Unfortunately, his intent to give the most ridiculous possible answer is thwarted by one Neera Tanden of something called the Center for American Progress, who, with an apparently straight face, nominates August 26, 1920 (the day American women gained the right to vote) — an answer that begins by placing 20th century America at the center of the Universe and proceeds downhill from there.

Other 20th-century answers (the assassination of Archduke Ferdinand, Hitler’s invasion of the Soviet Union) are at least more serious, and I think that Anne-Marie Slaughter‘s nomination of the still-very-recent-by-historical-standards signing of the Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1776 is even defensible. But then what about the Glorious Revolution of 1688, which arguably laid the political and intellectual groundwork that made the Declaration possible?

Is the public debt a drag on economic growth? Economist Salim Furth reviews the evidence here and finds cause for alarm.

My own instincts are substantially less alarmist, but it should be noted that unlike me, Furth (and those he quotes) have spent substantial time thinking hard about this question.

Christy Romer, writing in the New York Times, deems the Earned Income Tax Credit a more palatable alternative to the minimum wage. So do I. (So, I feel confident, do the great majority of economists). But there is almost no overlap between Romer’s reasons and mine. I believe her reasons are wrong.

First, Romer observes (correctly) that while the minimum wage tends to reduce employment (though perhaps not by very much), the EITC has the opposite effect. That’s because the minimum wage is essentially a tax on hiring unskilled labor, while the EITC is a subsidy. When you tax something you get less of it; when you subsidize something, you get more.

But, contra Romer, that’s no reason to prefer the EITC. Since when, after all, is it automatically better to have too much of something than too little? Underemployment and overemployment are both bad things. Indeed, if the minimum wage (for whatever reason) has very little effect on employment while the EITC increases it substantially past the efficient level, that’s a good reason to prefer the minimum wage.

The Future of Freedom Foundation plans to livestream my talk this afternoon, titled “More Sex is Safer Sex and Other Surprises”. I believe you’ll be able to find the stream here. Starting time (I think!) is 6PM.

Update: livestream cancelled for techical reasons but high quality video will be available in a few days.

Friday March 1 Tuesday, March 5 (note date change!): Our occasional commenter Sierra Black will discuss polyamory on the Katie Couric show; 3PM eastern time in many cities, but check local listings.

Monday, March 4, 5:30PM: I’ll be speaking in the Economic Liberty Lecture Series, sponsored by the Future of Freedom Foundation, at George Mason University in Fairfax, VA. I’m a little unclear on the exact location; this link and this link seem to contradict each other — but they do both give phone numbers to call for further information. Admission is free.