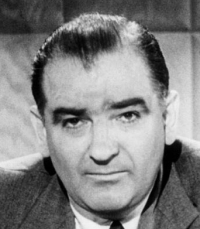

Ronald Coase has died at the age of 102. I am therefore reposting, with minor changes, the appreciation I wrote a few years ago for his 99th birthday.

In the theory of externalities—that is, costs imposed involuntarily on others—there have been exactly two great ideas. The first, forever associated with the name of Arthur Cecil Pigou (writing about 1920) is that things tend to go badly when people can escape the costs of their own behavior. Factories pollute too much because someone other than the factory owner has to breathe the polluted air. Nineteenth century trains threw off sparks that tended to ignite the crops on neighboring farms, and the railroads ran too many of those trains because the crops belonged to someone else. Farmers keep too many unfenced rabbits when they don’t care about the lettuce farmer next door.

Pigou’s solution—and it’s often a good one—is to make sure that people do feel the costs of their actions, via taxes, fines, or liability rules that allow the victims to sue for damages. Do a dollar’s worth of damage, and you’re charged a dollar.

Pigou endorsed this policy not because it seems fair, though it does seem fair to many, but because it yields, under what he believed to be very general conditions, the optimal amounts of damage. We don’t want too much pollution, but we don’t want too little, either, given that pollution is a necessary by-product of a lot of stuff we enjoy. Pigou offered a proof—now standard fare in all the textbooks—that his policies lead to the perfect compromises, in a sense that can be made precise.

The second great idea about externalities sprang full-blown from the mind of a law professor and subsequent Nobel prize winner named Ronald Coase, who stunned the profession in 1960 by pointing out that Pigou’s argument runs both ways. If you breathe the pollution from my factory, I’m imposing a cost on you—but at the same time, you’re imposing a cost on me. After all, if you lived somewhere else, you wouldn’t be complaining about the smoke and I wouldn’t be getting punished for it.