If you’re a novice investor, looking to get into anything from the stocks to Bitcoin, someone is going to tell you that you can reduce your risk by Dollar Cost Averaging — that is, investing the same dollar amount every month. That way, this person will tell you, you are buying more of the asset when its price is low and less when it’s high.

Please do not take investment advice from this person.

I explained in The Armchair Economist why the above argument is just plain wrong, and why Dollar Cost Averaging is actually riskier than a Readjustment strategy where you invest (say) $1000 and then periodically adjust your total investment up or down as necessary to maintain its value. The logic is compelling. But the sort of people who Dollar Cost Average tend not to be the sort of people with much of an appetite for logic. So today let’s go down a different road. I’ve actually done some calculations to show you how the two strategies are likely to pan out.

Imagine a (very volatile) asset, currently selling for $1, which either doubles or halves in value each month, with equal probability. [I know, I know, the asset you’re looking to buy behaves very differently than this one. So feel free to make some other set of assumptions and re-do my calculations. You won’t get exactly the same outcomes, but you’ll probably get outcomes that are similar in spirit.]

Now let’s imagine one hundred Dollar-Cost Averagers, each investing one dollar per month for 10 months. At the end of that ten months, the average investor will be ahead by about $30. That’s not bad.

Let’s also imagine one hundred Readjusters who each invest $11.83 up front and then, at the end of each month, either withdraw or deposit funds to bring their investment right back to $11.83. Why $11.83? Because that way, these hundred Readjusters will earn, on average, exactly the same $30 that the Dollar-Cost-Averagers earn over the course of ten months.

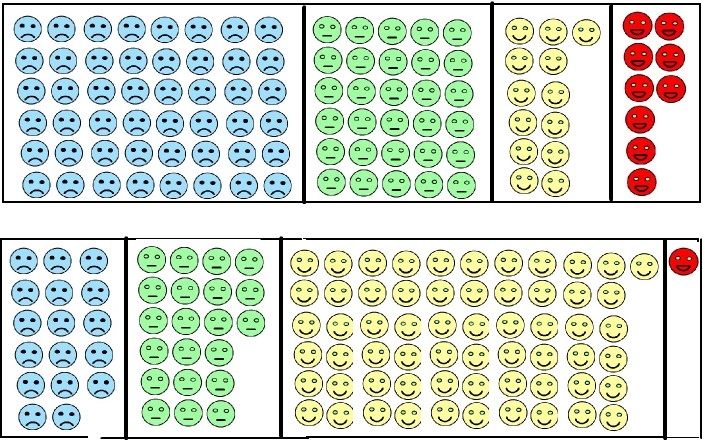

Okay, both strategies do equally well on average. But of course, if you’re one of these investors, you probably won’t be average. So I set my computer to calculating the distribution of outcomes for each group. Here is the result, with the DCA investors on top and the Readjustment investors on the bottom:

The blue guys have actually lost money. The green guys haven’t lost anything, but they’ve gained less than the average $30. The yellow guys have done better than average, and the red guys have done better still, earning over $90, which is three times the average.

Here’s the good news for the Dollar Cost Averagers: Nine of them have earned over $90, whereas only one Readjuster has earned over $90. That’s pretty much the end of the good news. In the money-losing blue category, there are far fewer Readjusters than Dollar-Cost-Averagers — about 17 versus 48. That’s right; almost half the Dollar-Cost-Averagers lose money, while only about 1/6 of the Readjusters do. 61% of the Readjusters are in the very happy yellow category, earning between $30 and $90. Only 13% of the Dollar-Cost-Averagers make it into that bracket.

Does that prove that Dollar-Cost-Averaging is inferior to Readjustment? Of course not. It all depends on what you’re looking for. Dollar-Cost-Averagers are more likely to lose money, and more likely to earn below-average returns, but in exchange, they get a 9% chance of extraordinary success while their Readjusting neighbors have only a 1% chance. Maybe that’s a gamble you want to take. That’s fine. In other words, it makes perfectly good sense to choose Dollar Cost Averaging in order to increase your risk. The guy who told you to use it to decrease your risk is still 100% wrong.

There are, of course, various real world considerations that got left out here. Different investment strategies, for example, have different tax consequences, and you might want to modify your strategy for that reason, but there’s no reason to think that after those modifications, you should be doing anything like Dollar Cost Averaging.

I want to reiterate that even before I did these calculations, I knew (at least roughly) how they were going to come out, because I trust the underlying logic (which, again, can be found in The Armchair Economist). The larger moral is that logic is trustworthy.

The whole matter is complicated in real life by two factors:

1) Nobody actually KNOWS what the characteristics are of the assets they are going to buy…they only know the characteristics that it has historically had (and, as everybody knows, “past performance is no guarantee of future results”).

2) Nobody actually knows what the characteristics are of the assets that you are going to be USING to buy those other assets…the assumption that you have some store of value that is relatively stable compared to the assets you are planning to buy would have caused you great trouble if you were in the Weimar Republic in 1922 (interesting book I read was Fallada’s “Wolf among Wolves”, which gives an interesting depiction of life in 1923, I think it was recommended by Tyler Cowen).

You’ve got to know when to hold, know when to fold, and I certainly can’t fool myself into believing that I do. The best I can think of is being able to identify investment opportunities that are almost certain to fail (just let a friend who has lots of cool ideas invest it, and you’ll have nothing more to worry about!), and avoiding those. But then, I had opportunities to buy BitCoin back when it was less than a dollar a coin, and never did (I did try mining, on a normal computer, a couple of days way back when, but got nothing).

It’s kind of reassuring to know that the gurus on the radio who recommend Dollar Cost Averaging really aren’t any wiser than I am, thanks for that.

If I can’t predict whether stock prices will go up or down in the short run, but am confident that returns will be positive in the long run, then it makes sense for me to invest as much money as I can as soon as I can, which translates to investing a roughly similar sum every payday.

This ends up looking quite a bit like DCA, doesn’t it?

Also, is it really fair to say that the two investment strategies do equally well on average when one requires an $11.83 investment up front (and possibly much more if you’re unlucky at the beginning), and the other requires $1 per month for 10 months? The NPV of the first is significantly higher, especially when using the high discount rate implied by an expected return of $30.

#2 – it would look like DCA for someone with much more $ than you. you’re just doing the best you can.

#1 – the gurus are smart enough to know DCA is an effective pitch to get people to keep giving them money no matter what the returns are

I think @3 makes a fair point. To evaluate the Readjuster strategy relative to the Dollar Cost Averaging strategy, we’d need to account for the cost of borrowing $10.83, to be paid off at a rate of $1/mo.

And if we insisted on using a realistic rate of interest for that analysis, then presumably we’d also want to re-run the entire analysis using a more realistic rate of return on stock investments.

Query for Landsburg: Have you taken your own advice? That is, as a young person, did you attempt to evaluate how much you might save for retirement, and then attempt to borrow that sum in order to invest it in the stock market?

Hm. I never had the pleasure of studying finance. And upon reflection, I see that modeling the financing costs of implementing the Readjustor strategy is more complicated than I had initially recognized, because we’d need to account for the monthly gains/losses.

In the real world, if you had no assets other than a steady job, what kind of financing arrangement could you establish with a bank to implement the Readjuster strategy? Maybe you could borrow sums with the legal obligation to use your stocks as collateral–but I expect the lender would charge a rate of interest commensurate with market risk.

Also, would you then establish a new loan every time you needed to add money to offset losses? The transaction costs alone could become prohibitive. Or would you initially borrow more than the amount you plan to invest upfront so as to have spare cash on hand to top off the account? In that case, you’d need to incorporate those costs into the analysis. How would you calculate the amount to hold in reserve?

Then you need to calculate the risk that the Readjustor defaults on her loan(s), thereby impairing her credit score for the next seven (?) years. Dollar Cost Averagers don’t seem to bear a comparable risk.

And after you’ve figured all that out, then you might want to calculate your opportunity costs–that is, the forgone opportunity of using your analytical skills for something more productive than trying to beat Dollar Cost Averaging. Even a sub-optimal strategy, if implemented, will beat a theoretically optimal strategy perpetually mired in analysis paralysis.

DCA has generally referred to a method of investing an *available sum* over time…so again if you have no pool of cash but rather are constrained to your paycheck, it seems to me you’re just lump sum investing at regular intervals as best you can. (DCA also seems to presume some amount of SR mean reversion to make the math appealing.)

Like nobody.really, I am having trouble seeing the advantages of the Readjustment strategy. It seems to assume that I have more money to invest, or that I have the ability to cheaply borrow to cover short-term losses. Usually it is risky to borrow money to cover losses. I am skeptical that it will be less risky or more profitable for the typical investor.

Roger: In a world with no transactions costs, the Readjustment strategy minimizes risk (for a given expected return). The reason why is simple: Each month there is a separate random price change. With DCA, you’ve usually got a lot more riding on the ninth and tenth price changes than you do on the first and second. With Readjustment, you have exactly the same amount riding on each price change. Thus you are maximally diversified.

Obviously we don’t live in a world with zero transactions costs. But the point is that if the usual arguments for DCA as a strategy for risk reduction were correct, they would apply just as well in that ideal world as they do in the real world. They are wrong in that ideal world, so they are wrong in general. (To put this another way: If your argument for DCA relies on transactions costs, then it is not the argument for DCA that I am trying to debunk.)

There might be arguments in favor DCA, or for something like it. But those arguments, in order to be correct, would have to say “DCA is a good idea despite the fact that it adds unnecessary risk”, not “DCA is a good idea because it limits risk”. The latter is just false.

The classic refutation of Dollar-Cost Averaging is a paper by George Constantinides. One way I’ve tried to explain the argument is:

1) Imagine two individuals Alice and Bob with identical preferences (identical risk tolerance). Alice inherits a million dollars in stock, Bob inherits a million dollars in cash.

2) Assume no taxes and transaction costs.

3) Observe that Alice and Bob should migrate to the same portfolio at the next point in time since their preferences are identical.

4) This contradicts the key idea behind dollar-cost averaging which is that you should move money gradually from one investment to another.

It’s debatable, I suppose, how one should define dollar-cost averaging, but I do think it is motivated by this intuition that money should be moved gradually into or out of risky assets.

As others have pointed out, the comparison Steve is making in the blog post is comparing apples to oranges. No DCA advocate would suggest that if you have a large pile of cash available now, you should invest it in equal increments spread out over your entire investment time period. And I doubt Steve is really advocating that a young person just starting to invest should try to predict their total investments over a lifetime, borrow the money now, and invest it upfront. That would be insanely risky.

So we really need to discuss two different situations.

If an investor has steady income arriving, it certainly makes sense to invest a portion of each pay cheque, whether or not you call that dollar cost averaging or think of it as simply investing as soon as the money is available.

The other case is when an investor has a large lump sum on hand to invest, and has a long investment horizon. In this case, it makes sense to use a form of dollar cost averaging. For example, with a 10-year investment horizon, it might make sense to break the initial investment into three pieces, invested today, a month from today, and two months from today. The expected returns of the two strategies will be very close, but the standard deviation of the second strategy will be much lower, resulting in less risk. An investor can choose the number of periods and the timing to balance the two, and can make the expected returns very close while still reducing the risk in a meaningful way.

This topic came up in 2010 on this blog, and at that time I exchanged email with Steven, since comments were closed on the post. The simulations I did at that time (which refer to some specific proposals made then) are also relevant for the current discussion. The results, along with discussion, are shown here:

http://jdc.math.uwo.ca/dca/

They’re really about different things: Dollar-cost-averaging is an appropriate starting point for discussion for someone who has a limited income-stream to invest. Readjustment is more about taking advantage of the fact that investments fluctuate more than they should. The right answer is probably more of a hybrid: Set aside some money every month for investment, and readjust between cash and various securities to take advantage of the existing variance. But it always depends on other aspects of the investor’s situation, like expected time to retirement, possible need for large amounts of money (buying a house), etc.

Eric, you say “should migrate to the same portfolio”. but over what time? Dan has an argument that it is better to dollar cost average over 3 months.

Two additional points:

1) It would be interesting if Steve told us whether he is contributing regularly to his retirement plans, or is keeping them at a constant balance. I think it’s pretty safe to assume that he is doing the former. So then the question is, if his analysis suggests that this is the wrong strategy, what aspects of the real world are missing from his analysis?

2) A serious flaw in Steve’s analysis is that he normalizes the investments to have the same expected return. Investment strategies need to be compared based on how much they return relative to the amount invested. It’s a standard fact that risk and expected return are related, so it’s no surprise that one can find a strategy with less return and less risk, which is likely what is happening here. (It’s tricky to know for sure, because the readjustment strategy requires a variable amount of capital that depends on the market behavior.) One could add a third strategy to the list: invest $300 in a bank account that pays 1% over 10 months. That has a return of $30, like the other two, but essentially no risk. Does that mean that it is better? Certainly not, since you are only earning 1%, rather than the 545% that the DCA strategy returns on average! (The latter is measured relative to the average amount invested, $5.50.)

Roger, the upshot is that Alice and Bob should “migrate to the same portfolio” *immediately*. This basically follows from the fact that your utility is a function of what you are invested in now (what you were invested in yesterday is irrelevant). Assuming no taxes, no transaction costs.

What is meant by “no transaction costs”?

Commissions on trading securities are close to zero for most investors. So we can ignore those transaction costs. But there is still the cost of the risk of a badly timed transaction. Markets fluctuate, and you will overpay if you buy at the wrong time.

Dollar cost averaging reduces that risk.

I am still trying to understand the argument against DCA. Do you have some simplified finance model where the risk does not exist? Is that risk just an illusion? Does the Readjustment strategy do a better job of reducing that risk? Am I making a conceptual error by thinking that I have lost money by making a poorly timed investment?

Eric (#10): Your Alice/Bob example is perfect, and I will probably steal it.

Another way to put this: Alice inherits $1,000,000 worth of stock, and wants to own $1,000,000 worth of stock in the long run. Do you advocate that she sell $900,000 worth immediately and then buy back $100,000 worth every month? If not, you’ve just rejected DCA.

Dan Christensen (and others): I assumed an interest rate of zero, just as I assumed zero transaction costs. If you (consistently) assume some other interest rate, you’ll get the result. But even if that weren’t true, you’d then have to argue that DCA is a risk-reducing strategy only for some range of interest rates, which means that the usual arguments, which do not mention the interest rate, cannot possibly be correct.

Roger:

Markets fluctuate, and you will overpay if you buy at the wrong time.

Dollar cost averaging reduces that risk.

That is the opposite of the truth. Since I’ve already explained why (in comment #9), and you just went ahead and repeated yourself anyway, I am forced to conclude that you’re just not going to bother reading/digesting anything that challenges your prejudices. So I don’t think I’ll waste any time repeating the explanation.

But if you choose to continue ignoring the logic, you might at least learn something by running your own simulation. Have you tried that?

I looked at several academic articles, to get an explanation. I found that 1979 George Constantinides article titled, “A Note on the Suboptimality of Dollar-Cost Averaging as an Investment Policy”. He says he assumes “no transaction costs”, but he really assumes something much stronger. He assumes that assets can be bought and sold without any risk from price fluctuations. Since the point of DCA is to reduce such risk, he says DCA is suboptimal.

He admits that his analysis does not apply to “gradual policies”, where there is a staged transition from one portfolio to another. He says those are often considered synonymous with DCA, but claims that there is a difference.

This is a straw man attack on DCA. If DCA means selling a stock portfolio in order to gradually buy it back, then sure, it is suboptimal.

I don’t see how any of this applies to real world investors. Dan posted some simulations that show that DCA can reduce risk in some cases.

If the investor is somehow able to figure out the best investment, then sure, he should immediately put all his money in that. If he waits, then he could be missing out.

There are empirical studies that show that the earlier you get all your money into the best long-term investment, then you are likely better off in the long term. But the DCA still reduces short-term risk.

Steve, even assuming an interest rate of 0%, do you really advocate that a young investor should borrow large amounts and invest that money as a way to reduce risk?

If you are allowing borrowing, then you must consider the risk not relative to the expected earnings, but relative to the initial capital. If I have $10, borrow $90, invest $100, and it goes down to $80, I’m not down 20%, I’m down 200%.

The typical investor does not have their lifetime earnings on hand, and borrowing to invest that (unknown) amount would greatly increase their risk.

The real world is complicated, and your analysis oversimplifies things to the point that you get a conclusion that is rarely going to be realistic, and which I doubt you yourself follow. As I asked earlier, what factors would your analysis need to take into account to give outcomes that are actually realistic?

Dan, the Readjustment strategy could pay off. Suppose that you can save $1k a month for the next year, and that the stock market is the place to be as all investments eventually win big.

The first month you save $1k, and also borrow $11k interest-free, to invest $12k. The market crashes the first month, and the value drops to $2k. So you save $1k, borrow another $9k interest-free, and bring your investment value back up to $12k. The next month the market crashes again, so you borrow another $9k and invest it.

Now it seems like you are way behind the DCA investor because you have huge losses and huge debts, and the DCA investor is buying at the bottom and looking at big profits. But not really. You have a highly leveraged position that will eventually pay off big, if you wait long enough.