Can you spot the flaw in this argument?

1) Over time, Bitcoin will become increasingly important as a global currency.

2) Therefore, over time, the price of Bitcoin must rise.

The first is a statement of (alleged) fact and hence not (in its raw form) susceptible to logical analysis. This is not a post about whether it is true, probable, possible, improbable or false. I’m just going to accept it for the sake of argument.

The problem occurs at the word “Therefore”.

I suppose that what underlies the “therefore” in some people’s minds is some instinct like this: “Prices have to equilibrate supply and demand. With supply fixed and demand growing, the price must rise”.

Here’s exactly where that argument goes wrong: Bitcoin has two relevant prices: The price of the asset itself and the transaction fee you pay every time you use it. If the transaction fee rises to equilibrate the supply and demand for transactions, there’s no obvious reason for the price of the asset to rise.

In other words: Yes, it is true that fixed supply plus rising demand implies a rising price. But when there are two prices, it’s not immediately obvious which one must rise.

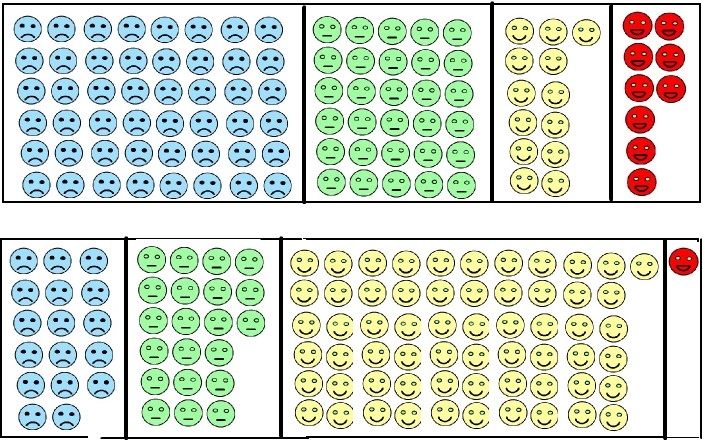

I can easily imagine a world like this:

1) The demand for Bitcoin transactions is extremely high.

2) Therefore the transaction fee is extremely high.

3) Therefore people use Bitcoin only for large transactions. Large transactions tend to be foreseeable. (I don’t buy a car without first thinking about it for a while.) Therefore there’s plenty of time to acquire Bitcoin just in time to make my transaction. Otherwise, there’s no reason to hold it. (And plenty of reason not to, just as there’s plenty of reason not to hold any other non-interest-bearing asset. For example, if you’re hedging against inflation, you can buy interest-bearing inflation-indexed bonds.)

4) Therefore, at any given moment, the demand for Bitcoin is quite low, although the demand for transactions is quite high.

It seems to me that much of what I read about the supply and demand for Bitcoin starts from the assumption that we can model the demand for Bitcoin the same way we model the demand for dollars or euros. But neither dollars nor euros have transaction fees, and that seems to me to make a world of difference.

Am I missing something?