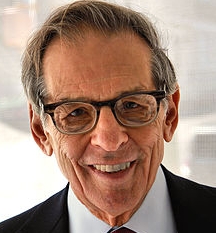

As I work my way through Robert Caro’s monumental four-volume biography of Lyndon Johnson, I’m repeatedly astonished by Caro’s gargantuan appetite for detail on the one hand, and his near total incuriosity about the big picture on the other.

As I work my way through Robert Caro’s monumental four-volume biography of Lyndon Johnson, I’m repeatedly astonished by Caro’s gargantuan appetite for detail on the one hand, and his near total incuriosity about the big picture on the other.

Case in point: We get almost 40 densely packed pages on the appropriations (eventually totaling $25 million) for the Marshall Ford Dam and another 30 or so on what a dramatic change the dam (and the electricity it brought) made in the lives of Texas Hill Country farm families. But unless I overlooked it, we’re never told how many of those farm families were affected — and are thus left with absolutely no basis for thinking about whether this dam was a good investment.

At another point, we’re told of a $1.8 million expenditure to bring electric lines to 2892 Hill Country farms. (This is, of course, over and above the cost of the dam, which presumably benefited many more than just these 2892.) This time, thankfully, we are at least told how many families are affected. But since the expenditure comes to $622 per family in a time and place when one dollar a day was a good wage, where there was no running water and very little communication with the outside world, and where the soil was bad and getting worse, this raises the question of whether that $622 could have been better spent relocating that family to a better place. (All the moreso if we top off that $622 with the family’s pro rata share of the dam cost.) Caro never even acknowledges the question, pausing simply to celebrate the benefits of electricity, which, he seems to imply, were great and therefore (!) justified the expenditures.

Well, there are two ways you can get the benefits of electricity. The electricity can come to you, or you can go to it. Sometimes one way is better; sometimes the other. When conditions are as Caro describes them — with the land essentially worn out, starvation rampant, and everyone too poor to get a fresh start in, say, Austin — there’s a pretty good likelihood that the guy who could have helped you move, but instead spends a bundle to bring you an electric line, has something other than your best interests at heart.

I’m not far enough along to be sure of this, but after a little peeking ahead, it’s beginning to look like this is how Caro’s going to treat the Great Society also — hundreds of pages on the details of the legislation, hundreds more on the good it (allegedly) did, and not a single inquiry into how much more good somebody could have done with expenditures of that magnitude.

And then there’s this passage, which I feel compelled to assure you I am not making up:

Continue reading ‘Power Transmission’