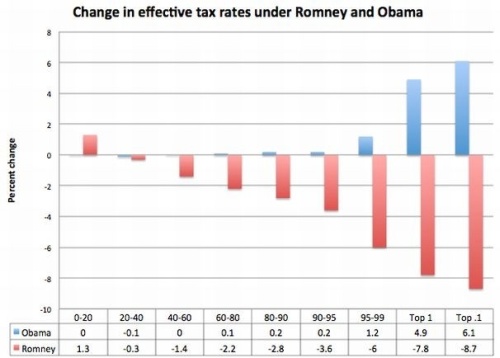

Ezra Klein, quoted with approval by Paul Krugman, offers this chart of how the Obama and Romney tax proposals will change rates for taxpayers in various quintiles:

What we’re supposed to infer, according to Krugman, is that

we have an election in which one candidate is proposing a redistribution from the top … downward, mainly to lower-income workers, while the other is proposing a large redistribution from the poor and the middle class to the top.

But no such thing is remotely true. What we actually have is an election in which both candidates are proposing massive redistributions from the top downward, one slightly less so than the other. You’d never know this from looking at Klein’s chart because it illustrates changes in rates, whereas what actually matters is the rates themselves. It makes no sense to ask whether any particular group ought to be paying more or less without reference to how much they’re already paying.

Indeed, this is a classic example of what I once called the “Grandfather Fallacy” — by focusing on changes instead of absolutes, Klein’s chart conceals any existing inequities and hence treats them as “grandfathered in”.

Fortunately, Greg Mankiw has provided the numbers that allow us to make the requisite correction. Here, according to Mankiw, are the current tax burdens on various income groups (counting transfers as negative taxes, as of course one should):

Bottom quintile: -301 percent

Second quintile: -42 percent

Middle quintile: -5 percent

Fourth quintile: 10 percent

Highest quintile: 22 percentTop one percent: 28 percent

That “-301 percent” means, for example, that a typical family in the bottom quintile receives $3.01 in net transfers for every $1 that it earns.

By adding these numbers to the numbers in Klein’s graph, we can construct a picture that actually depicts something interesting, namely the projected tax burdens for each group. It looks like this (the vertical axis represents percentage of income):

Note, for example, that, contrary to the impression you might have gotten from Klein’s and Krugman’s posts, both plans place the highest percentage burden on the top 1%, and both plans place a negative burden on the middle quintile — though Obama’s does both of these things to an ever-so-slightly greater extent than Romney’s does. There’s room for disagreement about which plan is fairer, but no room, I think, for disagreement about which chart is relevant.

Now my chart is still imperfect, partly because I’ve added apples to — well, not oranges, but perhaps some other breed of apples: Mankiw’s numbers count transfers as negative taxes whereas Klein’s numbers appear to ignore transfers altogether — this being, come to think of it, yet another reason to discount those numbers. But of course this entire exercise is fraught with imperfections in any event, because it extrapolates from imprecise promises made by the candidates and fails to account (among other things) for the effects of the various loophole closings that Romney has hinted at but failed to specify. And, to restate the main point, for all its imperfections, this is a chart that at least addresses the relevant issues, which is a lot more than you can say for Klein’s chart or Krugman’s screed.

Klein says: “The lowest fifth of earners, by contrast, would see a small tax increase of 1.3 percent under Romney’s plan, owing the federal government an additional $143 extra on average.” [From web page you link to]

Does any of the lowest quintile pay (net) income tax? I see numbers in the range of 48% of households pay no income tax. SO, how could they earn more? Could it be they dip into the pockets of those paying taxes less? This is a creative notion of a tax increase if you ask me.

Indeed.

“Mankiw’s numbers count transfers as negative taxes….” Fine. But what is a “transfer,” and why give it more attention than other government policies that redistribute wealth among social classes?

Is the fact that the US launched a war in the Mideast based on false pretenses, with predictable consequences for energy and defense firms, reflected in Mankiw’s numbers? Are the bailouts of large banks reflected in Mankiw’s numbers? Is the fact that Bain Capital extracted $58.4 million in profits from Steel Dynamics, but left the firm bankrupt with a $44 million pension deficit to be borne by the federal Pension Benefit Guarantee Corporation, reflected in Mankiw’s numbers? Is the fact that the corporate form limits the liability that investors would otherwise face – in effect, transferring wealth from innocent 3d parties to shareholders – reflected in Mankiw’s numbers? More generally, are all forms of externalities reflected in Mankiw’s numbers?

I’m doubtful.

Admittedly, many of these factors are historical, and I don’t expect the election of either Romney or Obama to change them. But I do expect Obama to pursue more measures to clamp down on certain kinds of wealth transfers from poor to rich, as reflected in the establishment of a federal Consumer Protection Bureau, than Romney. And I wouldn’t be surprised to learn that Mankiw’s numbers omit the consequences of ObamaCare, which I expect shift wealth toward the lower classes – and which Romney proposes to repeal.

In sum, I share Landsburg’s view that the Klein/Krugman analysis fails to reflect a larger viewpoint. But I offer a similar critique of Mankiw’s analysis. Ultimately, whether any of the charts really reflects the relevant issues irreducibly depends on which issues you regard as relevant.

nobody.really –

That sure is a lot of spin. The analysis is a fairly straight-forward one, and the issue is not complicated. I can’t think of any good theoretical reason to include “externalities” in the above graphs, except to try to make them look differently. Presumably, the reason transfers count as negative taxes is because they are financed through the very taxes that the recipients do not pay. Are you suggesting that the incomes of the rich are a function of the “externalities” incurred on others?

Yes, in part. I suggest that markets are imperfect, so the incomes of everyone may have this dynamic.

This is part of a larger critique of libertarianism: People often look at some government action and conclude that it reflects some wrongful transfer of wealth. People less often acknowledge that a LACK of government action may also reflect a wrongful transfer of wealth.

Landsburg correctly references the “Grandfather Fallacy”: It makes no sense to ask whether any particular group ought to be paying more or less without reference to how much they’re already paying. But by the same rationale, it makes no sense to ask whether any particular group ought to be paying more or less without justifying the Grandfathered distribution of wealth from which they make payment.

Before proceeding, I would prefer knowing how you define “externality,” “transfer of wealth,” and market “imperfection.” And while you’re at it, a definition of what specifically makes a person “rich” would also be helpful.

To me this:

Middle quintile: -5 percent

is just silly. When you take into account dead weight losses and the fact that Government programs often do not deliver what we would buy, I do not think it is possible to effectively subsidize the middle class. It is therefore silly to try. We would be better off eliminating most benefits to the middle quintile and lowering taxes to the same.

nobody.really,

Wouldn’t those other things you mentioned mostly be a straight percentage of earnings. I.E. wouldn’t the benefit of defense be a fixed percent of each persons income. Other externalities like pollution might be tilted toward the lower income doing more damage per dollar of income (A rich guy does not drive 10 times as much as a lower income guy and probably drives a newer less polluting car)?

I think it is absurd to decide that the absolute numbers are the only thing that matter. When people talk about tax increases and tax cuts then, amazingly, they are talking about tax increases and tax cuts. When Landsburg changes the subject from the direction to the absolute numbers then, not to surprisingly, Landsburg is changing the subject.

Right now, Obama is proposing raising the rates on income over $250,000. That means, unless the Laffer Curve overrules static analysis that the tax paid by people making more than $250K will increase. It seems to me that a fair description of Obama’s plan is “a redistribution from the top … downward, mainly to lower-income workers,”

Right now, Romney is proposing significant reductions in the rates paid by the very rich. Romney has not mentioned any loopholes he wants to close so, until he does, I think it is safe to assume that those loopholes will not just affect the very rich. Therefore, a fair description of Romney’s plan is “a large redistribution from the poor and the middle class to the top.”

You can quibble about whether increasing the deficit helps or hurts various groups but Krugman’s point is basically correct.

Krugman, in this post, never said the rich pay almost all the taxes. He didn’t mention the proper level of taxes people should be paying. He did mention that Romney will cut taxes for the rich and Obama will raise taxes on the rich. It appears that Krugman printed the truth. He didn’t mention the absolute amount that various groups pay. Why put words in his mouth?

nobody.really,

Interesting that you site the bailout of banks and not the bailout of auto companies. Also interesting that you think Steel Dynamics went bankrupt. It did not. You’re thinking of GST. Steel Dynamics purchased GST. Both were Bain investments at one time.

I really don’t see why it’s wrong to focus on the changes to the status quo of taxation.

Politics, after all, is (usually) a business of incremental change to the status quo.

Romney wants to decrease the current redistribution, Obama wants to increase it.

As such, they want to go into opposite directions. If you think that redistribution is bad, you go with Romney. If you think massive and growing inequality is bad, you with Obama.

For political purposes, the changes – not the absolutes – are exactly what you want to focus on.

And then, of course, “transfer income” (SS, Medicare, Medicaid, mostly) doesn’t nearly cover all Federal expenses, and most non-transfer expenses such as infrastructure construction/maintenance, law enforcement, supervision/regulation, bailouts, wars to secure access to oil, funding of research, etc. arguably disproportionally benefit those with more income/wealth.

Beware definitions; words acquire meaning within specific contexts. That said….

I think of a market imperfection as a circumstance in which the classical economic model (or laissez faire policies) predictably produces sub-optimal results.

I think of an externality as a form of market imperfection whereby a decision maker does not bear the full consequences of her decision.

I use transfer of wealth to refer to the consequence of a social policy by which … uh … control over resources transfers from one party to another?

As for “rich” – dunno. RPLong introduced that term at Comment 3; ask him/her.

Dunno. Not even sure I have a framework for guessing. But I suspect that the benefits from increased defense spending are greater for Lockheed Martin than they are for the rest of us. Doesn’t mean that the costs were not justified. But when it comes time to determine which social classes derive the most benefit from government policies, it is unclear to me why this policy should not be among the ones under consideration.

Perhaps. But I suspect that there were externalities that resulted from our recent and ongoing financial meltdown: the people who benefitted from creating the risks may not have borne the full cost of their actions.

Not to overlook the burdens that my Gremlin imposes on society. But this merely underlines the point: Without knowing the aggregate consequences of things like financial collapses and my Gremlin, I have difficulty establishing a framework from which to judge the current or proposed allocation of wealth.

Fair enough, and thanks for that catch!

With Klein and Krugman’s view, applying the brakes to your car could be described as making the car go backward because, after all, the acceleration is in the backward direction.

@neil wilson, advo:

The issue is that Krugman et al are framing the issue as if Romney wants to make the tax system regressive as opposed to simply slightly less progressive. They’re not lying so much as they are taking advantage of the fact that most people commit the grandfather fallacy by sutomatically assuming that either the status quo or the status quo ante is/was just.

A way I like to rebut simplistic “tax cuts for the rich!” rhetoric is to ask that person to imagine that an extreme leftist seized power and raised the top tax rate to 100% while reducing all other tax rates to 0%. Once the leftist was overthrown, what would they support changing the tax system to? Unless they themselves are an extreme leftist or a mindless status quo conservative, they will almost certainly support “massive tax cuts for the rich” and similarly “massive tax hikes on the poor and middle class” in order to achieve a tax system that isn’t so extremely progressive.

This highlights that most people using this rhetoric don’t really oppose the idea of tax cuts for the rich in the abstract – they implicitly agree that there is a point where taxes on the rich can be too high, they just disagree on where to draw the line. But as such rhetoric gives absolutely no help to decide us where to draw the line other than the rather useless measure of what the status quo is, it has no substance.

(Note that this also applies in the opposite direction to conservative Republicans who don’t really oppose government spending but use rhetoric that only has substance if you support zero government spending).

Would it be fair to say that “relative to Obama’s tax policy, Mitt Romney is proposing a large transfer from the poor and middle-class to the rich?”

On another topic : One thing he is proposing is further deregulation of an already lightly-regulated banking sector. Won’t a failure to protect mom-and-pop deposit accounts from high-risk investment activities lead, eventually, to another taxpayer-funded bailout? And even before the need for a bailout arises, won’t the implicit guarantees allow financiers to earn risk-premium returns (taxed at capital gains rates) knowing that in fact the risk is borne by the Federal Government and, ultimately, the taxpayer?

If you get paid to bear a risk that I bear for you, isn’t that a transfer of wealth from me to you?

nobody.really –

Specific definitions are the only things worth discussing. We can lurk in the shadows of ambiguity all day and only ever really speak to ourselves.

Much of what you’re saying falls victim to the Paradox of the Heap. That is, it seems true enough to say that 5,000 grains of sand are a heap, but what about 4,999? 4,998? 4,997? Eventually, you reach a point at which you are no longer talking about “a heap of sand,” but it is impossible to identify the single grain of sand that makes the difference. Let me explain…

You define a market imperfection to be a predictable sub-optimality. Sub-optimal for whom? How many factors are we willing to introduce to the analysis before we have introduced too many? Is it “fair” to say that so long as there is a critically large income gap, the entire market has failed? If so, is it “fair” to point out that human desires are always unlimited, while resources always limited?

The strength of a market imperfection argument, therefore, depends not on the issues, but rather on ambiguity. A mass of poor people seem like a problem. A single poor individual may not be. Between those two extremes lies a wasteland of vaguery about which nothing specific can be said.

Point #2: externalities defined to be situations where an actor does not bear “full responsibility” for his actions. If I dump toxic waste into a public river, the situation is obvious. If I drive my car to the grocery store, it is less obvious. If I drive my car to deliver much-needed food to starving individuals, it is far less so.

The strength of an externality argument, then, depends on the notion that every externality is strictly negative and easy to identify. But there is a whole spectrum of human action that could be classified as an “externality.” In fact, no one could ever truly be said to bear the FULL consequences of any action. There will always be ripple effects. So, again, when have we reached the “critical point” at which an externality becomes a problem?

The reason I asked for definitions is because I suspected your point had greater strength when it was vague. At least, that’s how I see it. There is a problem with this.

You can always hold out on any strong point (like Landsburg’s, above), by saying, “But wait… there are still other factors to consider.” If the factors are material – like non-taxable income sources from transfer payments, then by all means include them. If these factors are vague moral sentiments, however, the objection seems unreasonable.

At least, that’s how I see it.

Mike H,

I think the word ‘transfer’ is the problem. Suppose the current policy was to transfer $3 from you to me, and Obama proposed to transfer $4 from you to me, while Romney proposed to transfer $2 from you to me. I suppose it would be fair to say that Romney was proposing to transfer money from me to you relative to current policy, but the ‘relative to current policy’ part should be emphasized. The honest thing to say would be that Romney was proposing to transfer less money from you to me, but it is still a transfer from you to me.

The point is that focusing on directional changes alone is meaningless (or worse) as it requires / presupposes a view of the “fairness” of the status quo. But nobody ever wants to define their standard of fairness. As Henry describes, in purely directional terms one can say the exact same things about *any* reduction in top rates, even if the top x% were paying *all* of the taxes. This is great for demagoguing, but not shaping optimal policy.

For many people including those nobody.really calls libertarians, it seems a reasonable starting is the observation that people who *create* wealth — by coming up with a product or service people want, or a business process that allows us to make more with less — benefit society even if those gains are not taxed at all (e.g. whether they reinvest it, or spend it, or bequeath it to whomever they choose). In order to preserve the issue in moral terms, other people we might call ‘redistributionists’ respond that those who have more must have instead taken some or all of it wrongfully from others. Personally I don’t see how anyone can really convince themselves that this is how most wealth gets distributed in a free society (if nothing else, transferring from poor to rich would by definition seem to encounter practical limitations.)

Of course theft and fraud are “wrongful transfers”, and just about everyone would agree that government exists to prevent that. But in general it seems the rest of the conversation just involves policy preferences which (as an honest utilitarian would acknowledge) have little to do with rights or fairness.

Come on boys and girls.

NOBODY talks about tax cuts and tax increases on an absolute basis. It is always on a relative basis.

You put your foot on the gas to accelerate and you put your foot on the brake to slow down. You raise taxes (rates) and you lower taxes (rates).

Krugman was basically correct. When you change the topic from relative tax rates, which Krugman was talking about, to absolute levels, which Landsburg was talking about then YOU ARE CHANGING THE TOPIC.

Of course, if you are talking about the absolute amount of taxes then you should be talking about ABSOLUTE AMOUNT OF TAXES. I know that is a strange topic to people but you shouldn’t just be talking about the level of income taxes but the level of all taxes.

Income taxes are progressive. Virtually every other tax is regressive.

It is amazing that liberals always forget that the income tax is progressive. Conservatives always forget that other taxes exist. Even other “income taxes” like FICA are regressive.

I believe I share iceman’s understanding, stated at Comment 18, of the dynamics of this discussion. I have not understood anyone to challenge the accuracy of Klein’s, Krugman’s, or Mankiw’s statements, but to challenge the (unstated) assumptions about the “rightness” of some status quo from which a given policy deviates (the Grandfather Fallacy).

Suffice it to say, I don’t fully share iceman’s view about the rightness of his “reasonable starting [point],” or his understanding of resource allocation. But we can save that discussion for a more appropriate thread.

Neil,

Talking about the level of all federal taxes isn’t really that strange a topic to us people. The CBO data that Mankiw cited — and that Steve used for his plots — are based on all federal taxes: individual income taxes, social insurance taxes, corporate income taxes, and excise taxes.

Clarifying a misleading statement is not the same as changing the topic. If someone said something that caused people to believe that putting your foot on the brake made a car move backward, it would not be changing the subject to point out that the car would still be moving forward. That would simply be replacing obfuscation with a little common sense.

@neil wilson:

Not changing the topic at all, just keeping the forest in view for the trees. Here’s an analogy. I have a headache and want to take advil. Well the question I face is always whether to take a next one. Surely it can be a good idea sometimes to recall I just took 13 already.

The difference being debated here is one about rhetoric and the appeal to gut reactions in the voters. About manipulation. ‘Soak the rich’ sells. But at a certain point if you keep doing it, it goes too far. Looking at the total level as well as the change lets each of us consider if we have gone too far, not far enough, or just the right distance. This is not changing the topic, this is perspective.

“NOBODY talks about tax cuts and tax increases on an absolute basis. It is always on a relative basis.”

If true, that’s the problem. But in my experience those who invoke the “fairness” of greater progressivity in particular NEVER want to define they would consider a “fair share”…it’s just always more.

Speaking of perspective and manipulation, has anyone accused anyone of “taking hostages” over the fiscal cliff yet?

Neil,

You raise taxes (rates) and you lower taxes (rates).

Raising tax rates does not equal raising tax revenue. Lowering tax rates does not equal lower tax revenue. There is plenty of empirical evidence for this.

What I am advocating is a sort of “zero-based budgeting” in the rhetoric of fairness. Zero-based budgeting is the corporate management technique that requires each division to satisfy all of its expenses each year from scratch. The traditional alternative to zero-based budgeting is to presume that each department will have a budget pretty much like last year’s. Like the Grandfather Fallacy, traditional budgeting treats the status quo as a natural starting point.

A zero-based approach to fairness means recognizing that a policy is made fair or unfair not by improving one man’s prospects or diminishing another’s; it is made fair or unfair by its conformity to absolute moral standard. We may disagree about what that moral standard should be, but attempts to resolve our disagreement should be a lot more enlightening than “I have a right to my property because it’s been there for as long as I can remember.”

Is it fair to reform the allocation of resources at the expense of rich people? That’s the wrong question. The concept of “fairness” properly applies not to a change in the allocation of resources, but to a level of benefits. The traditional approach invites us to ask whether someone’s allocation should go up or down. The zero-based approach demands that we go directly to the question: What is the right allocation? The answer to that question should be a number, not a word like “less” or “more.”

“What is the right allocation?” is a hard question. But to attack all reallocations as immoral is to deny that the critical question could ever be worth asking. A reflexive opposition to all reallocation amounts to nothing more than a defense of the status quo just because it is the status quo.

“Raising tax rates does not equal raising tax revenue. Lowering tax rates does not equal lower tax revenue. There is plenty of empirical evidence for this.”

I love Art Laffer.

Can anyone give me an example of changing a tax rate in the 30% to 40% range where the amount of revenue raised and the change in tax rate do not go in the same direction?????

You stated there is “plenty” of evidence.

Can anyone show me the best evidence where a change in income tax rates went in the opposite direction? My guess would be lowering the rates from 90% but I am not sure.

Please don’t show me evidence on changes in capital gain rates. That is far easier to move from year to year. Please don’t show me where people push income from December to January as that also is easy to do. Show me where taxable income changed year over year and didn’t reverse.

Thanks

“Can anyone give me an example of changing a tax rate in the 30% to 40% range …”

I will once you explain to me how you prove a theorem with examples.

My point is this: Ken (who still lacks an in initial) caught you in an error of logic. The right rejoinder is, ‘oops, you are right, I made a slip but in this case it doesn’t matter because we are not near the hump in the Laffer curve.’

Neil:

Using the CBO data that are here:

http://www.cbo.gov/publication/43373

and the top marginal tax rate data that are here:

http://www.taxpolicycenter.org/taxfacts/displayafact.cfm?Docid=213

I made plots of the top marginal rate and the total federal taxes paid per household (total federal taxes divided by number of households). I restricted the plots to the period from 1987 through 2009 because you are interested in situations were the tax rate was between 30 and 40 percent. Here’s the plot:

https://www.dropbox.com/s/zdvaqbbrzcuibfm/Laffer.png

You can draw your own conclusions, but my observations are:

1. Taxes per household grew steadily after the top marginal rate was increased in 1993.

2. Taxes per household declined rapidly when the top marginal rate was dropped slightly in 2001.

3. Taxes per household grew rapidly when the top marginal rate was dropped to its current level in 2003.

4. Taxes per household dropped significantly in 2008 when the tax rate remained the same.

I think my third observation is the example you asked for with 5 question marks.

Of course the top marginal tax rate is only part of our overall tax scheme, but it seems to be the part that is attracting the most attention in this debate.

Remind me to never wager with Thomas Bayes.

Allegedly a 10% tax on yachts priced more than $100,000 caused a lot of problems in that industry. Yachts (and planes, and liquid capital) are quite mobile, making it easy for buyers to shift transactions to other jurisdictions. Allegedly web-based sales are driven in part by the desire to evade taxes.

But no, I have no studies to cite.

And yeah, I’m not aware of instances in which a small income tax cut triggered increased revenues all by itself. I would not be surprised to see correlations; I’d be surprised to see causation.

(Is “taxes per household” a standard measure? It would seem to conflate tax revenues and household formation. But maybe that’s as good as it gets.)

nobody.really:

I used taxes per household because that is the way taxes are represented in the CBO data. On the upside, this measure normalizes for population growth. On the downside, this measure could be affected by societal changes in the make-up of households.

To me, one of the most stunning things in the CBO report is this: in 2000 we were receiving a net tax revenue* per household of about $12,000 (2009 dollars). In 2009 the net was about $2,000. The 2000 number was the peak; the typical value was about $8,000.

*Net tax revenue is taxes collected minus direct cash transfers back to households. And, despite what Professor Krugman might have us believe, this transfer is from the high income quintiles to the low income quintiles. It would still be so after implementing the Romney plan.

I stand corrected…”NOBODY[.really] talks about tax cuts and tax increases on an absolute basis.”

As Robert Nozick pointed out, people who talk about “distributive justice” often try to rig the game by pre-supposing this can only be evaluated in terms of end-state principles, rather than *process* principles. For the latter, there is no “number”; *any* distribution that results from a fair or just process (like voluntary exchange) can be seen as fair or just. (Which doesn’t mean we might not choose to alter it charitably.)

I’d add that while the symmetric counter “those who want lower taxes / progressivity don’t like to define their standard of fairness either” might often be true, in that case they don’t really need to; they can point to some baseline level of govt (taxation) to fund essential public goods out of *necessity*, and address their personal views of fairness via charitable means.

Oh, forgive me; I hit the ENTER key before I edited Comment 25, and I now see it’s full of typos. Here’s the corrected version:

__

What I am advocating is a sort of “zero-based budgeting” in the rhetoric of fairness. Zero-based budgeting is the corporate management technique that requires each division to satisfy all of its expenses each year from scratch. The traditional alternative to zero-based budgeting is to presume that each department will have a budget pretty much like last year’s. Like the Grandfather Fallacy, traditional budgeting treats the status quo as a natural starting point.

A zero-based approach to fairness means recognizing that a policy is made fair or unfair not by improving one man’s prospects or diminishing another’s; it is made fair or unfair by its conformity to absolute moral standard. We may disagree about what that moral standard should be, but attempts to resolve our disagreement should be a lot more enlightening than “I have a right to my agricultural subsidy because it’s been there for as long as I can remember.”

Is it fair to reform the welfare system at the expense of its neediest beneficiaries? That’s the wrong question. The concept of “fairness” properly applies not to a change in benefits, but to a level of benefits. The traditional approach invites us to ask whether welfare benefits should go up or down. The zero-based approach demands that we go directly to the question: What is the right level of welfare benefits? The answer to that question should be a number, not a word like “less” or “more.”

“What is the right level of welfare benefits?” is a hard question. But to attack all cuts as immoral is to deny that the critical question could ever be worth asking. A reflexive opposition to all cuts amounts to nothing more than a defense of the status quo just because it is the status quo.

Steven Landsburg, Fair Play, Chap. 7, “Fairness I: the Grandfather Fallacy”

I love the Yacht Tax. It makes people crazy.

Let’s think logically for a minute.

You have two similar yachts. One sells for $50K and the other for $55K. The tax should make no difference.

You have two similar yachts. One sells for $110K and the other sells for $121K. I am on weaker ground, but I assume the tax makes very little difference.

You have two similar yachts. One sells for $95K and the other sells for $104.5K. It seems to me that the yacht tax would be very significant. I would assume there would be very strong demand for the $95K yacht and virtually no demand for the $104.5K yacht.

Am I making any sense? Was there a boom in yachts in the $95K range?

I assume there should have been a small decline in all yachts over $100K and the decline would get bigger as the yachts got closer to $100K. On the other hand, there should have been a big increase in boats just less than $100K.

However, this tax has nothing to do with the Laffer Curve.

Of course, the decline in boat sales probably had more to do with the economy than it did with the tax EXCEPT near the cutoff line.

Was the tax a good idea? I don’t know. We raised a certain amount of money and we reduced the sales of some boats by a certain amount.

Neil:

—

“Was the tax a good idea? I don’t know. We raised a certain amount of money and we reduced the sales of some boats by a certain amount.”

—

George Will wrote about this tax in 1999:

http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/WPcap/1999-10/28/010r-102899-idx.html

In his essay, he cited the results of a study conducted for the Joint Economic Committee, and summarized that the tax–which applied to other luxury items in addition to yachts–was projected to yield $31 million in revenue for 1991. Instead it collected $16.6 million and “destroyed 330 jobs in jewelry manufacturing, 1,470 in the aircraft industry and 7,600 in the boating industry. The job losses cost the government a total of $24.2 million in unemployment benefits and lost income tax revenues. So the net effect of the taxes was a loss of $7.6 million in fiscal 1991.”

I didn’t read the JEC study, but, assuming that George Will provided a fair summary of the study, we did reduce the sale of some boats, but we didn’t raise a certain amount of money. We lost money and jobs.

People do, evidently, respond and react to incentives.

Neil:

Something to keep in mind for your speculation about how the tax affected yacht sales: the tax applied only to the amount over $100K. So a yacht that sold for $101K would only incur a luxury tax of $100.

nobody.really: Pretty cheeky…but your ‘typos’ are revealing. E.g. if you really equate property rights with agricultural subsidies, we are clearly not talking about anything remotely resembling a *process* principle. I can’t speak to SL’s personal version of what some call ‘libertarianism’ but he himself I think calls ‘consequentialism’. I did say that those who believe in some form of *absolute* limit on redistribution can indeed construct a bottom-up “number” in terms of publicly-provided benefits (whether we call that “fairness” or something else). But this is quite different from putting a “number” on the amount of earned wealth we deem to allow people to keep. At least in terms of a fair process…

How’s this for a process pinciple: If we can disparage defense of agriculture subsidies based on the Grandfather Principle (and I do), then we can disparage property rights based on the Grandfather Principle.

Property/autonomy rights are social constructs. Which things we choose to recognize as “property” depends on social forces, and change as social forces change. Whether I can own a slave, expect ranchers to bear the cost of keeping their cattle out of my corn, or expect to make copies of Disney movies within 36 years of their creation, or sexually harrass my employees all depends on which point in history I consider.

So for Klein, Krugman, or Mankiw to obsess over government policies labeled “taxes” and “transfer payments,” while ignoring all the other policies that transfer wealth among social classes, strikes me as silly. If someone wants to analyze the consequences of puplic policies on transferring wealth, my “process principle” would be to treat all wealth-transferring policies (and omission of policies) even-handedly — or to candidly acknowledge when you don’t.

I get your point about “what about other transfers?”, I presume people were just trying to focus on things that are fairly directly related to tax policy in ways we can actually hope to measure.

On the broader issue we can quibble at the margin about examples of “property”. (Although I don’t find yours to be very on-point, e.g. Coase wasn’t affirming or denying property rights on either side, but rather saying the ultimate outcome will be determined by whose position is in fact more valuable, not by a judge’s assignment of liability).

However saying “let’s be even-handed about policies that reallocate more or less of people’s wealth”, irrespective of how they attained (e.g. created) it, is simply not a process principle. And “property is a social construct” is clearly endorsing some end-state principle. (Just so I know – do you consider a right to one’s life merely a social construct as well?)

So when trying to cast redistribution in terms of fairness, I would like people to at least “candidly acknowledge” when they are excluding considerations of process.

I don’t know what iceman means by “process principle.”

And I’m suspicious of what it means to say that a person “creates” wealth.

For example, I suspect that during their respective lifetimes, J.S. Bach created less wealth than Justin Bieber. What would account for the difference? Perhaps it’s personal qualities — maybe Bieber is more talented and harder working. Once you get over laughing that possibility off, you’ll rapidly come to the conclusion that the difference arises from the different social circumstances in which the two men were born. Indeed, if you imagine either man born in the year 5000 BC, you can imagine how small would be the wealth they might generate.

Thus, overwhelmingly, the wealth you might say any given individual created is a function of social dynamics that exist largely independent of the individual. If we could run a regression analysis on people and wealth, I suspect we’d find that talent and hard work would be weak explanatory variables; social context would be a strong one.

Then we can explore the issue of whether talent and hard work should be regarded as exogenous or endogenous variables….

Well, as I review all the circumstances in which people have been killed without legal consequence, I find that different societies have prescribed different rules at different times. So I can conclude that all those people living in other places and times were WRONG, WRONG, WRONG, and simply failed to appreciate the RIGHT AND TRUE views that prevail in our current place and time. Or I could conclude that it’s all a social construct.

In short, I regard the concept of a right as a social construct. YMMV.

I mean we might care not just about the ex post pattern of a particular distributional outcome per se (“end state principle”), but the process by which it was derived. E.g. a corrupt kleptocracy vs. a system of free voluntary exchange. (Maybe we refer to what you were describing, the process by which we choose between various outcomes or transfers (end-state or other) as a ‘meta-process principle’?)

What’s “YMMV”?

Sometimes I like to think of this as “not all inequality is equal”.

Also has much to do with absolute vs. relative levels of wealth, e.g. do people prefer a system where everyone is worse off but the distribution is narrower?

1. Ah. Thank you.

2. I care about both process and outcome.

I don’t imagine I need to defend the reason for caring about process.

But I also care about outcome. First, I’m not persuaded that I’m sufficiently skilled at evaluating processes to be able to detect when they create systemic problems. I can imagine systemic reasons why women would tend to marry older men. I could imagine that, when it comes time for child-rearing, this pattern would create a systemic reason for women and not men to leave the paid workforce. I could imagine that, over time, the combinations of these patterns would result in cultural norms about the appropriate roles of women and men. And I could imagine the need for social interventions to this arrangement to defend the rights of both women and men to act contrary to these social conventions. While the conventions may have arisen through a series of entirely consensual steps, the net effect may prove to constrain people who have not consented.

Also, I fear that I lack some of the qualities associated with homo econimus, and instead have the qualities associated with humans. I care about the way other people live, at least to the extent that I am aware of them. As a result, there are certain end states I will impose on you, regardless of the merits of a process that might have brought you to a different state. For example, I don’t want to see you enslaved or lacking for certain types of health care. I’m not imposing these outcomes on you to promote your utility; I’m doing to promote my utility. And because I’ve managed to persuade a large number of my neighbors to value these end states, too, you’re just gonna have to suck it up – at least until you can persuade these neighbors to change their views.

3. I’m skeptical about systems of free voluntary exchange. In Jane Austin novels, women freely choose among the loutish lads to whom they will submit body and soul in holy matrimony. And in Haiti people freely choose to attract any number of waterborne diseases. In contrast, where I live government taxes people and brutally compels them to get an education so that they will not be entirely dependent on others for a living, and brutally imposes on them a nearly endless supply of potable water. And, of all the people I’ve just described, if you think that I’m the one enduring coercion, you must be a libertarian.

In short, a person’s “freedom to choose” is only as good as the person’s options, and those options are constrained by a social context which the person did NOT choose. Thus, while I value choice as a means of enhancing individual and social welfare in many contexts, I’m not persuaded that polices such as taxation – which is imposed on people without their choice – always reduce people’s freedoms more than mere circumstance – which is also imposed on people without their choice.

nobody.really: “In short, I regard the concept of a right as a social construct.”

So do I mostly I think, but that doesn’t mean some aren’t worth defending. I think for example that rights to practice your own religion are fairly modern, arose mostly out of the experience of Europeans after Luther, are predicated upon the irrationality and moral failings of believers, and are entirely worth defending.

#40 – there’s no accounting for tastes, and I agree with the musical preference you espouse here. But it seems that to consider policy implications from that, you’re now saying all those Bieber fans are “WRONG WRONG WRONG”. There’s also Nozick’s famous “Wilt Chamberlain argument”: you spread Bieber’s wealth around, but the problem is people continue to buy his tickets voluntarily, so you do it again, and again…a formula for Leviathan-like continuous intervention?

#43 – just note that if you care about process, it’s difficult to critique a particular distribution that results from a seemingly fair or just process (like voluntary exchange) on grounds of “fairness”. But as I’ve said I don’t think an honest utilitarian is really making a claim to rights or fairness, rather saying “I’m sorry to take your resources but my algorithm simply says this will maximize my preferred social utility function.”

Is the prevalence of the grandfather fallacy the same thing as status quo bias?

I think this is a very interesting perspective, but while Landsburg is talking about the relative-absolute difference, it might be important to note the same problem on his aggregate chart. Placing the 0-20% group next to the others makes the effect of the tax plans look very small, but if you actually look at the two far right income groups, it appears that Obama’s plan taxes the upper class somewhere between 1.5 to 2 times as much. This is not in favor of or against his position, just something to consider.

“…. a person’s “freedom to choose” is only as good as the person’s options, and those options are constrained by a social context which the person did NOT choose.”

It seems in this statement that the “person’s options” are real and identifiable. It seems that “the social context which the person did NOT choose” is theoretical and undefinable.