This post is a first attempt to rank the efficiency of the Republican candidates’ tax plans, concentrating on six dimensions:

1) The tax rate on wages and/or consumption. A wage tax and a consumption tax are pretty much interchangeable; you can tax the money as it comes in or you can tax it as it goes out. So I’m treating this as one category. The “right” level for this tax depends on your forecasts for future government spending.

2,3,4,5 and 6) The tax rates on dividends, interest, capital gains, corporate incomes and estates. I believe these tax rates should all be zero. That is not a statement about how progressive the tax system should be. A wage tax and/or a consumption tax can be as progressive (or regressive) as you like. It is instead a statement that while all taxes discourage both work and risk-taking, capital taxes have the added disadvantage that the discourage saving. This simple intuition is confirmed by much of the public finance literature of the past 25 years. (Here is a good example.)

My personal preference is for a system substantially less progressive than the one we’ve got, but for purposes of this exercise I won’t penalize candidates whose preferences differ from mine. For the record, Romney, Huntsman and Santorum are the three who (as far as I can tell) want to maintain substantial progressivity, with Romney, uniquely among the candidates, preferring even more progressivity than we currently have.

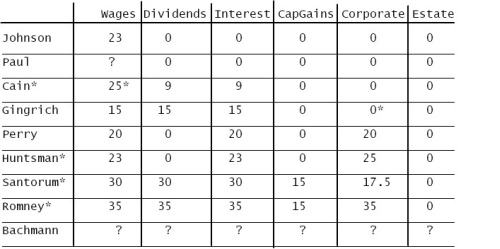

Here, then, is a chart, with candidates ranked roughly in order of their willingness to exempt capital income from taxation. I prepared this chart with a few quick Google searches (this is a blog post, not a journal article) and it probably contains errors. I’ll be glad for (documentable) corrections and will update the chart as they come in. Asterisks refer to further explanations, which you’ll find below the fold.

If we care about efficiency, we’re looking for zeroes in the last five columns. On the face of it, Johnson is the clear winner. But Cain’s 9/9/9 plan has two arguments in its favor that don’t appear on this chart. First of all, people are a lot less likely to bother evading one of three 9% taxes than a single 23% tax; therefore we’d have a lot fewer evasion problems under Cain than under Johnson. Second, it’s pretty easy to imagine Congress raising a 23% tax to 24% or 25% or 26%, but it’s a little harder to break the psychological barrier of single-digit tax rates, so Cain’s 9/9/9 might be more politically stable than Johnson’s 23. Therefore I’m calling this a tie between Johnson and Cain.

But the top six are all pretty good, except maybe for Paul, who hasn’t revealed his key number. Santorum is bad, Romney is atrocious, and Bachmann (who, as far as I can tell, has not bothered to release a tax plan) is an enigma.

Some explanations:

1) Cain stresses that this is a transitional plan, ultimately to be replaced by an even better one.

2) Cain’s plan consists of a 9% VAT, a 9% sales tax, and a 9% income tax. A VAT and a sales tax are not exactly the same thing (they end up getting levied on slightly different goods) but they’re close enough for this rough exercise; therefore we can lump together the VAT, the sales tax and the part of the income tax that taxes wages. That adds up to 27%, but a slightly more careful calculation tells you that Cain will allow you to keep 91% of 91% of 91% of your spending power, which is to say about 75%. Thus this counts as a 25% tax, not 27%.

3) Gingrich wants a 12.5% corporate tax with 100% expensing. This is equivalent to a 0% corporate tax together with a one-time transfer of assets to the government, so as far as its effects on efficiency, I’m calling it the equivalent of a 0% tax. For several reasons, I’d prefer a corporate tax that really *is* 0%, but I’m trying not to impose my personal preferences on these rankings (beyond a preference for efficiency), so I am giving Gingrich credit for the equivalent of a 0% corporate tax.

4) Huntsman, Santorum and Romney all endorse multiple tax brackets; I’ve put only the top brackets in this chart. Huntsman’s 23 should really be three brackets: 8/14/23. Santorum’s should be 10/20/30. And Romney holds the remarkable view that our flawed political system has somehow settled on exactly the optimal system of six brackets, which he would preserve in its entirety.

I’d be interested to know where on this list

* Barack Obama would fit

* the current Australian tax system would fit

In Australia, the top marginal rate is 46.5%, including a health care levy. You need to earn $180k/year before you start paying this. I haven’t counted a disaster recovery levy that’s only being applied in 2011-2012. Estate taxes are 0, I think. Companies are taxed at 30%, but dividends are franked, so when the company issues dividends, they are treated as income, but the government rebates the tax they charged the company. Interest is treated as income. Capital gains are taxed as income, but if you’ve kept the asset for a year, the rate is halved. My guess is that this puts us just above the mystery woman?? However, people can put pre-tax income, which then gets taxed at 15% (up to a lifetime limit), or post-tax income (which will not get taxed) into their individual retirement accounts, where the capital gains etc are not taxed.

It would be interesting to see the equivalent exercise for trade and immigration policy. I suspect that Johnson would trounce the other candidates.

I’m wondering about Ron Paul’s number too, presumably you have to tax something. He’s said many times that he’ll eliminate the income tax and not replace it with a sales tax, but he also proposed this plan which doesn’t mention it.

Also, for what it’s worth, Cain recently said for the poor he would make it “9-0-9”, eliminating the income tax, and ruining the cutesy slogan he’s built up for months.

The real question on my mind is spending though. I’d like to see your ranking of their proposed budgets as well.

One more thing, I haven’t seen a comprehensive list, but Romney said he’d reduce the top corporate rate to 25%, and eliminate Div, Int, and CapGains for people making less than 250K, so technically, he should have an extra bracket I think. (Still pretty crappy, though)

The link to chari.pdf does not seem to work.

@Mike H

You forgot our 10% GST (VAT equivalent)

Harold: Thanks. The link works now.

I think Ron Paul wants to abolish the IRS and all current federal taxes, since his ultimate goal is to make the government extremely small. The only revenues he wants are user fees like gas taxes when you drive on federal highways.

P.S. Paul, when he was asked what to about the 50% of Americans who don’t pay income tax, responded “We’re halfway there!”

Here is the plan according to Ron Paul’s website:

http://www.ronpaul.com/on-the-issues/taxes/

“Ron Paul supports the elimination of the income tax and the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) … To provide funding for the federal government, Ron Paul supports excise taxes, non-protectionist tariffs, massive cuts in spending.”

Yah I’m pretty sure Ron Paul would eliminate 98% of the federal government and default on the national debt and all obligations including social security and medicare.

You don’t really need a tax plan once you’ve done that.

In which case he is number 1 by a long shot isn’t he?

If I could wave my magic tax-and-spending wand, I would crank up Georgist ( http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Georgism )and Pigovian taxes ( http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pigovian_tax ) to 100%. I would then take a portion of the money collected, and subsidize things with positive externalities to their pareto-efficient level (Pigovian subsidies). Then I would drop all other taxes to zero, and take a look around and see how close to balanced we were.

Assuming that we still needed some money (though full land value taxes and taxes on pollution should bring us a fair way to balance), we could set the tax on wages at an appropriate rate. If we wanted some progressivity while maintaining a flat income tax, we could include a wage subsidy (think of it as a form of negative income tax) — a flat 25% income tax would roughly pay for an hourly wage subsidy equal to the poverty line for all working Americans, and would also allow us to drop the minimum wage. In other words, anyone in full-time productive work would receive a check from the government equal to the poverty line, plus any wages they negotiated from their employer (minus 25%).

As a side note, the 25% level is just for illustration. If Georgist and Pigovian taxes, minus Pigovian subsides, yielded a positive number, you could fund a portion of the subsidy directly, and lower the flat tax on wages.

That’s pretty much off the top of my head, though. I would be interested in hearing arguments on either side, though.

On point 3, you seem to have left out “new equipment purchases” after “100% expensing.” I must be slow today, because I can’t see the equivalency to a zero rate (after a wealth transfer).

I love Johnson! (Who’s Johnson again??)

I’m gonna assume this ranking is not necessarily a guide to “electability”.

Professor Landsburg,

Many thanks for your post!

I’ve been a big fan of your books and now this blog for several years now. As I’ve never commented here before I do apologise that my comment turned out quite lengthy – it was actually inspired not only by this post but by a whole series of your posts and comments on taxation. It is really not so much about the Republican candidates as about the overall framework of assessing tax policies.

My particular point of interest would be the capital gains tax – I am aware of your views on the subject, but this is one of perhaps two major points where I could not totally agree with you. (The other one is curiously the immigration policy, which is also apparently now a hot topic in the US presidential campaign.)

Your last five columns (Interest, Dividends, Capital Gains, Corporate and Estate) are somewhat different in nature (although there are some similarities) so I would like to comment a little bit on each one.

The following points are based on the premise that it is fair and sensible to tax labor (wage) income for a certain percentage thereof (which to me is still debatable).

I believe 2 major points to be taken into account when discussing tax policies are practicability of administration and economic sense.

The practicability of administration is not only the amount of paperwork involved, but also the costs borne by both the taxman and the taxpayer in relation to tax avoidance. The IRS has to lose some revenue to successful tax avoidance schemes, retain more staff and process way more paperwork to prevent successful tax avoidance. The taxpayers have to generally pay too much attention to paying complicated taxes, adjusting their lives and businesses (often in a very inefficient manner) to avoid excess tax and pay all those endless advisers and tax lawyers.

So a good policy guidance here would be to minimize tax incentives to reclassify income. All those costly and economically inefficient attempts to classify personal expenses as legitimate corporate costs, salary and dividends as capital gains etc. and then to cover it up really present a large net loss to any developed economy. The part of GDP created by various income reclassification and tax avoidance/deferment activities is quite similar to digging trenches and then promptly filling them back – people are busy, many are content and even happy, but a huge amount of resources gets diverted from productive uses or outright wasted.

The principle economic sense to me here is to avoid both penalization of productive behavior and distortion of information sent by the market equilibrium to the largest possible extent.

So, if our premise is that we need to tax fruits of labor in a consistent and fair manner and tax them only once we need to separate income created by a person’s labor and income generated by using past proceed that have already been taxed.

Let me comment on the the taxes mentioned in the original post individually:

Estate tax

This one is really by all means a harmful one which you discuss in sufficient detail elsewhere so there is no need to spend any time on this. I believe it a mix of heritage of ancient pre-income tax ideas of social levelling and outright populism.

Ancient social justice ideas: lets make sure everyone can get a fresh start (or a re-start) in life. It is also based on a nice-to-hear notion that people a really so equal that given equal starting opportunities they would achieve equal outcomes. Don’t think anyone seriously believes this, but people keep saying this. Another example of this “fresh start” idea is a “jubilee year” (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jubilee_(biblical) which, despite being so ancient and exotic was still popular with some left-wing thinkers in 20th century (I can only think of Zeev Zhabotinsky (Russia/Israel), but there must be more. All those heritage ideas might be interesting to historians, but they share one pronounced trait – they never work, at least not in the announced manner.

….and outright populism (Yes we know there are plenty of ways to avoid this tax and no, we do not know why someone should be penalized for leaving a bequest as opposed to taking a champagne bath on board a private plane headed to their Tahiti mansion in their latter years, but we feel it will appease the populace and bring us some votes…)

Corporate tax

This one again indeed amounts to double and under current system sometimes triple taxation and makes investing in America less attractive for foreign investors – this can’t be such a terrific idea, right? If the idea is that Americans pay taxes because they have full access to socioeconomic benefits provided by the USA and enjoy political representation, what is the rationale for indirect taxation of foreign investors via corporate tax? To discourage them from investing in US companies and to encourage companies to incorporate/move their profit centres elsewhere? To induce the companies to engage in hardcore lobbying so that they do not pay that much tax after all? Or just to have them to spend probably as much time and money thinking about tax implication of their decisions as about the business sensibility of these decisions?

It also provokes overspending by businesses – even a 100% shareholder might prefer to spend on a not-so necessary private jet, “client entertainment” and palatial offices and then on endless lawyers to justify it, than shop for a better bargain for stuff he really needs himself but with 45% less money (after 35% corporate and 15% qualified dividend taxes – I am not even talking about state taxes). The wage taxes also have a similar effect by the way, but let’s for now assume it is necessary evil.

Dividends, capital gains and interest taxes

These 3 taxes are similar in a way that they are all levied on proceeds of utilization of one’s capital.In your post about a year ago( link )you argue that the capital gains tax should be abolished altogether because it amounts to double taxation, as all the capital used to produce those capital gains should have been already taxed at some point in the past.

What is important here is that rates of return and resulting capital gains fluctuate widely for comparable investments. So why exactly do they differ? It is important both from the economic sense and administration practicability point of view.

Your colleague David Friedman in his blog post ( link ) observes that only some portion of the capital gains which is in fact interest-like can be treated like interest.

Any extra income (basically anything above the average interest rate) is a result of skilled labor (also known as investment management). There is of course a fair deal of luck and risk taking involved on top of pure intellectual work, but is it a good idea to give luck and risk-taking any tax advantages over labor? Lady luck is (hopefully) not deterred by taxes and excessive risk-taking can easily become a serious negative externality as we now happen to know from experience.

So (unlike D. Friedman who seems to fully refute your logic) I believe it would be fair to apply your original logic only to the interest income and the notional interest component of capital gains and dividends. I would agree that this chunk should be relieved from taxation as direct proceeds of utilization of capital already taxed. As far as I know In Belgium there is a notional interest deduction on corporate tax. As we are not in favor of the corporate tax we could apply the same logic to the capital gains and dividend taxation.

There is a similar logic for dividends. Should an entrepreneur who pays himself a salary rather than a dividend be taxed differently? Correct me If I am wrong but under your preferred system of 0% corporate and 0% there will be much less salary paid in the US? Why pay salary if you can transfer a certain number of shares to an employee and then pay tax free dividends out of tax free corporate profits? You can even create a special “staff holding” subsidiary in your corporation. Its shares won’t cost much, as they will not be liquid and will not really give any control over anything (so the new employees will not have to pay much income tax when their shares are initially transferred to them), but will have a nice dividend. If you tax any dividend above the average return (aka notional interest) on an equal basis with other kinds of income, you will easily avoid these unwanted effects.

On interest income proper we could maintain principles already in existance in some countries – we can set up certain benchmarks like, say interbank lending rate +/- 3% and tax anything in excess as income. The notional interest can be established along the similar lines

The main principle here I think is that anything materially different from the average rate of return is a result of either of intelligent work (coupled with luck and risk) or tax avoidance and should therefore in both cases be taxed.

And of course another important matter is practicability of administration. It will be extremely impracticable for the tax authorities to separate work compensation from capital gains if the incentive to package all sorts of their income as capital gains were so immense for taxpayers. Last time I checked many European private equity and financial services multimillionaires packaged their compensation as capital gains on certain funds and trusts and paid, say, in the UK 15 -18% instead of 40-50% income tax (depending on tax year). (I presume the Wall Street and Connecticut guys are not really behind on this.) These people usually started off with no capital to speak of and got all their riches as result of their labor, luck and risk taking (but hardly by utilizing any previously taxed capital of their own).

As I understand what they do is to use the non-traded nature of their assets to show its value as very low when the units are initially transferred to them and using full or even inflated value when cashing out. So most of their total compensation gets taxed at a much lower rate (or at 0% under your proposed system).

So if the capital gains tax is totally abolished there is a risk that soon your plumber can start asking you to transfer money to a certain trust or a non-traded investment vehicle instead of handing you a bill… Sure there are transaction costs to this, but if you shift the tax burden from the capital gains tax to the income tax the incentive to use such loopholes will significantly increase.

If the capital gains tax is totally abolished (as opposed to being a subject to appropriate notional interest deductions) it will most likely either become a giant tax loophole or (more likely) any resulting tax relief will soon regulated out of existence by endless IRS checks and safeguards.

P.S. Actually, your completely justified point that proceeds from what has been previously taxed should not be taxed again suggests that our initial premise than it is fair to tax labor income lacks internal consistency.

What is a wage of a highly qualified professional if not 90% or more returns on capital previously invested? Education and work experience that are main drivers of the value of your labor do not come free, or for that matter cheap. Fair enough, some of that investment has never been taxed: lost earnings and foregone fun are fortunately at least not taxed. But when you pay a university fee, or rent your accommodation near university as opposed to staying with your parents, or even pay for the Internet connection to read econ blogs you usually do it out of the money someone paid taxes on.

So at least some portion of the labor income is always also created by capital that has been previously taxed once…

Once again, sorry everyone for such a long post! I guess I have just been accumulating ideas for too long :)

Your comments and counter-arguments are highly appreciated!

@Michael: I am very positive about your proposed combination of Georgist and Pigouvian taxes (although with some tweaks) but simply wouldn’t dare to make this comment any longer…

What, exactly, is a “non-protectionist tariff??” (cf Ron Paul, as quoted by @Keshav Srinivasan) Is it a tariff intended to harm domestic industry instead of support it?

Mike, I’m just guessing here but maybe it’s an equal tariff on both imports and exports. But I think the larger point is that the revenues collected under his plan would be pretty much infinitesimal, because he plans to do away with essentially the entire federal government (not immediately, but presumably that’s his goal over the long-term).

my plan:

Many economists have called for a consumption tax to replace the income tax. Invested money that is never spent promotes economic growth and has been compared to indiscriminate charity. The problem is that it is difficulty to make a consumption tax that is simple and progressive. So one way to achieve the goal might be to make it so a person can put as much money as they want, pre-tax, into an IRA. Then allow people to take as much as they want out of their IRA at any time but tax all withdrawals. You tax income not put in an IRA and the withdrawals at a same progressive rate. You could also allow people to buy a car or home in their IRA and rent them at market rates. The result would be a progressive consumption tax. You would also want to end the Corporate profits tax.

http://un-thought.blogspot.com/2011/10/how-is-this-for-progressive-consumption.html

I think Cain’s final plan is the “fair tax,” a 23% consumption tax. That sounds exactly like Johnson’s plan so we can’t have Johnson ~ Cain_1 and Cain_1 < Cain_2 ~ Johnson.

@Floccina As someone who also was in favor of the consumption tax some years ago, may I pose 2 questions that eventually made me reconsider:

1. On the economic sense of this tax: Why exactly do we think that incentivizing people to overinvest is a good think to do? We sure critisize attempts to have them overspend (e.g. via the estate tax) so why shifting the equilibrium in the other direction is a good idea? In an open economy most of this extra investment will end up overseas anyway because any additional home investment will push rates of return further down and promote export of capital.

2. On the administration of the tax: is there any practical system to separate consumption from investment and resist massive avoidance? Will I be not allowed to rent a house from a company I invested in (instead of buying this house)at the price we both agree on? Who and how will define “market price” for each individual home and car? Will my neighbour’s ill-behaved dog and tobacco smell inside my car come into the calculation (just an example)? They sure will be when negotiatin on real market price. If I am not allowed to pull my little trick, what about me renting from Bob’s company, Bob renting from Ann’s company and Ann renting from mine? Will the IRS check every single customer transaction to check if the consumer is somehow affiliated with the company via investment and if the price contains some kick-back of prior investment as opposed to a legitimate discount?

What about investment and consumption abroad? You probably do not want to be a US customs official trying to establish if all those margheritas inside an approaching tourist have not in fact been provided to him free by a bar in Tijuana he invested in… Seems not really possible to enforce all this in a practical manner to me.

On the other hand, if under your proposed IRA plan all investments will have to be pre-approved by some bureaucrats to avoid abuse, how will this affect both freedom and economic efficiency?

Dmitry Kolyakov: good post. Disguising wages as capital income is to my mind one of the reasons why we have capital taxes, and why we should continue to do so. That “anything materially different from the average rate of return is a result of either of intelligent work (coupled with luck and risk) or tax avoidance and should therefore in both cases be taxed” seems to be an excellent idea. Are there any practical problems with impemnenting this? Are there other loopholes for avoidance?

I also like to observation that earned income results from previously taxed income, although the link is not so direct.

Dmitry Kolyakov:

Thanks for your long and very thoughtful posts. I am busily digesting them!

Keshav Srinivasan: “Mike, I’m just guessing here but maybe it’s an equal tariff on both imports and exports.”

I rather doubt his plan would include amending Article I, Section 9, Clause 5 of the US constitution.

I would interpret “non-protectionist tariff” as meaning that the tariff would be applied without discrimination to all goods, as opposed to a tariff intended to benefit a particular industry.

@Dmitry: Good questions. Actually I thought the distinction between risk-taking and ‘pure’ labor is a key underpinning of a market economy (and the glaring flaw in the labor theory of value). In this case, I can spend the same amount of time analyzing two stocks, or a stock and a bond, and conclude that one warrants a greater risk premium — which would presumably fall under SL’s deferred compensation argument. If so, wouldn’t the average market return from a — purely passive — index fund be a more appropriate (risk-adjusted) benchmark for determining the labor/skill component than some (uniform?) “notional interest component”? E.g., should it be considered a positive return on my labor if I didn’t even beat the index? Conversely, should the majority of investors (who by definition underperform the index net of transactions costs) get a tax credit?

On dividends, I’m no accountant but I believe that in the US the distinction doesn’t apply to a true entrepreneur e.g. “sole proprietorship” b/c all business income flows straight to the personal 1040. However I think you may be right that for C-Corps, eliminating the corporate tax (for all the reasons you cite) would remove the source of the double tax on dividends, so those would then be best considered as ordinary income (as long as we’re all agreed on an income tax).

At some point doesn’t the wasted gray matter from all of this strike one as a strong argument for a much simpler code (and possibly a minimal state)?

P.S. Being from MN I happen to know that as a congressional candidate Bachmann has flirted with the consumption tax… so her opponent immediately ran ads saying she wanted to raise taxes on food and clothing (not mentioning the part about eliminating the income tax of course).

@Iceman: Thanks for your comments. I do agree that there is a distinction between risk-taking and “pure” labor and I am also not too happy about the labor theory of value… However, as I said in my original comment I do not really think risk-taking (or luck for that matter) should have tax advantages over pure labor. Pretty much every country taxes lottery and casino winnings after all.

Some debate is of course possible on whether risk should be taxed the same as labor, but as soon as there is a difference, administration and avoidance problems immediately arise.

I’ve actually also been thinking about average market returns for relevant asset classes as a basis of deduction, but there are two importaint considerations:

The asset class premiums (in your example, an equity market premium)are, as I understand widely believed to be a product of higher volatility and lover liquidity of certain assets compared to the “risk free rate” (to which high-quality debt market rates are the closest proxy). That is, they are risk premiums.

So in your example, where you invested, but could not beat the index you will be taxed on the proceeds of your risk-taking (the premium of the index over the risk free rate) while being effectively given tax relief for the loss due to your labor being not productive in this case.

The second consideration is that applying this or that relevant index instead of a uniform notional interest based on the risk-free rate will inevitably be highly arbitrary.

So, let’s assume I am an early adopter of some Silicon Valley’s new new thing, and invest in a pioneering company, Pear inc. After some time, the idea gets popular, shares shoot through the roof, and I do not want to be there when all those new investors start searching for some actual cash flows. So I get out and make a very nice profit.

When doing my taxes, I of course want “the fruit basket index” to be used for deduction, as it is comprised of similar companies and has risen nicely. Than tax adviser A says that Nasdaq index is to be used. The TA B says, that some aggregate of all US shares should be used, while a crasy foreign TA C says that it should be the average of all developed countries’ shares. (and so on till we encompass the universe).

As you can imagine the answer seriously affects the resulting tax to pay. So who of my tax advisors is right? They all have loads of very logical considerations to support their causes (i do not want to waste space with examples, but you sure can imagine).

So to me, while the economic sence of using an index can be debated, the practicability here is highly questionable.

On dividends, I am no accountant either, and I think you are right about the sole prorietorship (and some partnerships, for that matter), but my example was really about a corporation, as we were discussing corporate and dividend taxes. The 100% shareholder was just an example to underline that people controlling the company while not being 100% share holders have even more incentives to support corporate overspending.

“At some point doesn’t the wasted gray matter from all of this strike one as a strong argument for a much simpler code” – fully agree!

Dmitry Kolyakov

On question number 1 all taxes cause some distortion is tax consumption worse than taxing work? I do not think so. Also we benefit from investment in other countries just as they benefit from investment here. Investment allows us to use resources more efficiently.

On question number 2 I noted that you could buy your home in you investment house and be taxed on the value. That tax would be based on market rates like property sometimes are. It is not perfect just better than what we have now IMO.

The best thing is to simplify and lower taxes. IMHO most tax money is wasted transferring money from the middle class and rich to the middle class and rich.

BTW I like the gas tax. It makes sense though I would like to see some experimentation with privatizing the interstates or if not privatizing putting tolls on them with electronic billing.

“On question number 1 all taxes cause some distortion is tax consumption worse than taxing work?”

If you mean to say that there’s no difference between income tax, and a consumption tax, then no. They’re levying the same channel of money, just at separate times.

Also, I wouldn’t say tax dollars are “wasted” with redistribution. If you tax an individual who lives a life of affluence, who may have otherwise placed that taxed amount in his bank account (causing deadweight loss) and thus prevented that money from being spent, it may not exactly be a bad thing to give that money to someone who may actually circulate it through the economy.

But one thing that confuses me: say that money is instead invested, and a tax is imposed on capital gains. Wouldn’t that be a detriment in the sense of it potentially deterring investors from investing as opposed to saving money? If so, wouldn’t that cause an additional deadweight loss? And if that is true, if you impose taxes on both capital gains, and a consumption tax, now you’ve only compounded the issue by further incentivizing individuals to refrain from consumption.

If that’s the case, then 0% tax would be ideal. But somehow I feel as if I am missing a crucial underpinning here.

Help?

@Floccina: I am sorry if my initial comment was somehow unclear, let me re-iterate it a bit in.

On Q1 – Well, most taxes indeed introduce some distortion, but it is perhaps exactly the essence of tax policy to steer this distortion in the right direction (discouraging negative externalises, like the gas tax you mentioned, for example).

So the question remains: Why exactly do we think that incentivizing people to oversave compared to their natural preference is a good thing to do? Because this is exactly what replacing income tax with consumption tax does.

Comparing “taxes on work” and taxes on consumption for all its populist/political value (honest working folk vs. the evil fat cat consumers) is somewhat confusing for our discussion here: what is really being compared is taxing all income on equal basis vs. incentivizing deferred consumption (aka. savings) by giving respective tax deferrals. When you tax consumption, you also tax income, albeit in a peculiar manner – last time I checked consuming was necessary to be able to work.

I am not necessarily saying that it is a bad thing to do, but I think we need to be clear as to if and why it is good if we are to support such a major change.

You say: ”Also we benefit from investment in other countries just as they benefit from investment here.” While that seems fair, but no argument is full when it considers only benefits is not the costs. Is there any rationale why a dollar invested somewhere in Mongolia in better for the US and its citizens that a dollar spent in a local restaurant near your home? If there is we need to carefully consider it and not just list the possible benefits.

I actually so far see 2 reasons why consumption can at least sometimes be better than (over-)saving:

Consumption is at least in part linked to the locality where you live (e.g. you will not usually outsource your haircut or routine medical treatment, or a restaurant dinner to, say, Malaysia, where all these are cheaper), while investment usually just follows the optimal risk/return ratio. So while for humanity as a whole the effects might theoretically be equal or even be greater for investments abroad, the positive effects in the first case are more likely to be directly experienced by you, the taxpayer.

The second reason is that savings do not equal productive investments. With real rates of return so small as they are now in most developed countries, many savers will not bother to actually invest all of their savings, keeping them instead in hard cash, gold or in other forms not convenient for business investment. Even if we set up this IRA hopefully we are not going to tell the savers where exactly to put their money? So this artificially turbocharged savings rate in an open free economy will have 2 side effects, both very bad – asset price bubbles and liquidity trap (a long post already, so will not further develop it). Both are very pro-cyclical and as a result make everyone very dependent on (often very inefficien) government meddling.

Q2 – I am afraid I do not really understand your answer.

I was asking how you will deal with people investing in companies that will hold their property for them (or their friends on a reciprocal basis) and subsidize their consumption in a variety of ways. For example, i can be such a hard worker that i actually sleep on my business premises (no matter that these premises look awfully like residential property, I work their in my study and have dinner receptions for my business partners once in a while). Will I be prohibited from having a company car, company phone and a company PC? I can always compensate the company for some cases where the private nature of using them is too obvious (at some rate, that me and my company consider perfectly market based…) As said, you sure can try to check all of these transactions via bigger better Big Brother-like tax authority. But again, what will it do to both efficiency and economic freedom?

Dmitry: I guess what I’m trying to say is that I find it inconsistent to decide that labor income should be the basis for taxation, and recognize an important distinction between labor income vs. a required return for (productive) risk-taking, but not then conclude that the risk premium (along with the risk-free rate) falls under SL’s deferred compensation argument. (Luck just goes with the territory, and good luck distinguishing that from skill). And again I also find it noteworthy for the labor/risk distinction that one can achieve the average market return via a purely passive investment. I agree that if one is really committed to deducing what remaining portion of an investment return is attributable to skill/labor, selecting an appropriate benchmark is key. While investment managers attempt to do that kind of attribution analysis all the time, subjectivity is unavoidable (but what parts of our tax code are purely objective?), and at that point I tend to conclude the whole exercise is “impracticable” at best, and illogical at worst.

The gambling example is interesting. One could probably at least argue that there is no skill involved in a lottery. While perhaps one could still counter-argue all of this is another form of double taxation, e.g. if all that is happening is an exchange of after-tax income (can/do we account for all gambling losses as deductions?), perhaps most people simply don’t consider this “productive” risk-taking, or don’t view the returns as representing a time preference decision?

Another one on the hard-to-spot frontier between consumption and investment: could anyone of the consumption tax proponents remind me why is buying myself a house is consumption and not investment, exactly?

A simple acid test for your convenience: please tell me which of the following is no longer an investment and why?

1 I purchase shares in a hotel company that builds, buys and manages hotels

2 I form a sole proprietorship that buys and operates a hotel

3 I form a sole proprietorship that buys and operates a long-stay hotel (like Marriott Execustay)

4 I form a sole proprietorship that buys a block of flats and rents them out to tenants (both short and long term)

5 I form a sole proprietorship that buys a house and rents it out to the highest bidding tenant

6 I personally buy a house and rent it out to the same tenant

7 I personally buy a house and rent it out to the same tenant who pays me in kind by letting me occupy a property he owns instead of paying cash

8 My dual personality problem ends, so i just buy a house for myself and let myself live in it as an in-kind return on my investment

Similar logic would work for all durable goods to some extent.

Dmitry, in case 7 by living in a house for some period of time when others could have been living in that house instead of you, I think you’re engaging in consumption. It seems to me that whenever you do something with resources which prevent others from using them, either now or in the future, that is an act of consumption. So both storing gasoline in your basement and burning it in your car would be consumption.

In cases 1-6, other tenants are consuming. In cases 7 and 8, you are.

Keshav, thanks for your answer!

Have you noticed that asked when my buying myself a house (and not consuming my rent or its value in kind) constitutes an act of consumption? Does it change your answer?

For simplicity’s sake let’s assume I am consuming all return on my investment (dividends, rent or in kind return) anyway in all cases.

Keshav, sorry if I was not clear in my question! I was asking about the initial cash outlay in all cases. When you live in a house, you clearly consume the value of your rent or possible rent, I was not questioning that.

@Iceman: I think the main difference between our positions is that you unlike me believe that risk-taking should not be taxed on par with labor income – am I right? Otherwise please show me what is exactly inconsistent in the original argument:

Any market investment return is a product of risk free rate, volatility accepted (i.e. risk appetite) and investment management work. Risk free rate should be except from tax (as per SL’s argument). While we recognize the distinction between risk premium and pure labor compensation we do not see a reason to give risk taking and fruits thereof a preferential tax treatment compared to labor compensation, so the only element qualifying for tax exemption is the risk-free rate (or a proxy thereof, such as a notional interest rate based on investment returns of highest quality debt products).

So where exactly is the inconsistency? We may disagree on whether the fruits of pure risk should be taxed, but this is a different premise, not an inconsistency…

While taxation of risk is certainly a value judgement, two points come to my mind in favor of taxing it _at least_ equally with labor income (which can, of course both be zero, if we so chose, the absolute number is not the point):

Too much risk is likely to be more harmful to the society as too much labor, so why should risk have more tax incentives?

Labor and risk-taking are indeed virtually impossible to separate, not only in the investment context, but in general (what part of the compensation for someone digging trenches is in fact compensation for the risk of injury?) so even if we decide that risk should receive different tax treatment, it will be not possible to make any practical use of it…

What you call a purely passive investment can also be termed pure risk-taking (accepting risk levels of a particular asset class in exchange for the respective risk premium).

When investment managers are playing their dirty little tricks to lure investors they are actually trying to asses their efficiency (e.g. skill) by comparing themselves to their peers operating withing a similar investment mandate (industry, debt/equity/mezzaine, traded/not traded, geography, etc.) as many of them are fairly specialized. So when they calculate their alpha coefficient (a metric of investment skill) they are weeding out beta coefficient (volatilty/risk) of the market/peer group specified by their investment mandate from the total returns. So selecting the appropriate beta is the key. And you are quite correct when you say that (without a defined mandate) the whole exercise of separating returns on skill from returns on risk will be impracticable and at worst illogical.

And that is exactly one of two major reasons why I suggest not truing to separate them at all for the purposes of taxation (while acknowledging the important theoretical difference).

On the gambling examples: while lottery is indeed a bit different, as it has little or no skill component, card games have been often compared to investing. Before a certain individual started writing books I do not really like that much, he wrote a decent book called Liar’s poker… And yes back than it was about real investment business. The proportion of skill and risk in a proper card game (such as the above-mentioned poker) can in my opinion be quite close to that in investing.

I am not sure I know how to tell a “productive” from a “non-productive” risk. To me, some risks are just linked to productive activities, while some are not, but the risk itsef is purely mathematical creature. Let’s assume we have just had a nice game of roulette and went to the adjacent bookmaker’s office to build on our luck. I bet on horses, you bet on whether CAC40 will out perform KOSPI today. Who of us is being more productive? Now let’s assume I am still at the bookie’s and you are a high-powered trader on Wall St. making the very same bet via actually buying and selling derivatives on the same indices. Has anything changed now? (apart from smaller transaction costs as there is now no greedy (and heavily taxed) bookmaker making money on your bets).

The only important thing really missing from the card games is the risk free rate – return on letting people use your money for some time.

The good thing is that in investment business there is a market for risk – people who want to offload their risks are willing to compensate you for it via risk premiums (unlike casinos, where usually only the risk-seekers congregate so they are all effectively paying the casino for letting them risk).

So risking in financial markets is usually a better idea than in a casino, but still there are clear parallels – so why the different tax treatment?

If you mean that risks you are compensated to take are productive I can see this distinction, despite calling for equal taxation of all risks – I am clearly not linking financial markets to gambling in terms of social value, only in terms of similarity of some basic components.

So this is clearly not meant to upset any investment professionals or their friends, and I apologise if anyone is somehow offended.

Dmitry, maybe we’re quibbling over semantics, but just to be clear do you agree that if you live in a house you are in some sense “consuming the house” for the time period you live there?

A couple of quick points

i think that saving/investing creates net positive externalities consumption on net creates negative externalities.

the fed government already polices peoples wages to keep them from avoiding FICA.

my taxing plan taxes all income the same

Keshav, I think this is indeed semantics – tell me, if I am living in a hotel, am I consuming a hotel in your sense? If yes, then yes, I am consuming the house, if not than also do not.

To me when I live in a house what I consume is the value stream of accomodiation. The monetary value of that stream is the rent (wheter I pay it to someone or to myself).

That is the essence of investment – you make an initial cash outlay in exchange for a series of future streams of value (either in the form of cash flows or in kind). When you consume however, you make the item you consume unavailable to other consumers forever in exchange for fulfilling your needs, and not some future streams of value.

@Floccina

“i think that saving/investing creates net positive externalities consumption on net creates negative externalities.” – well, that looks a bit contrarian to me, so the onus to support your thinking here should probably be on you. That is why I was asking you for a couple of times for some argument to support your opinion but never saw it (may be I missed it, please direct me)

I am sorry, but saying “I think X creates net positive externalities but Y creates negative externalities” without bringing any proof or even examples of both is just a scientific-sounding way of saying “I like X and not Y”.

“the fed government already polices peoples wages to keep them from avoiding FICA” – exactly, and it is already costly, complicated and tax avoidance is probably still not too rare. But finding hidden income is infinitely easier than checking _every single transaction_ for affiliation of parties and testing it for market pricing. And do not forget checking everything provided by your company for business/personal usage ratio. If you do not do this your proposed tax is not enforceable. Doing all this is both very costly and limiting to economic freedom and economic efficiency.

“my taxing plan taxes all income the same”, if giving indefinite tax deferrals for any income not consumed immediately fits your definition of “same” than yes.

Your initial question (at least on your blog) was “Would that work”. And while you of course have a right to believe that consumption is bad, and savings are good and refuse to discuss why exactly you believe so, my answer to your initial question would be no, it would not work. The tax authorities will either have to tolerate massive evasion/avoidance or become a version of the Big Brother (and I do not mean the TV show).

I do not think I can contribute anything more unless you chose to properly relate to numerous arguments and examples I posted in reply to you comments.

How do those who favor VAT over income tax propose to deal with the transition to a VAT that would threaten to tax again the wealth accumulated from already-taxed income?

Furthermore, what will keep a person from earning income in a no-income-tax jurisdiction and spending it in a no-sales-tax jurisdiction? Wealthy folks already manage to do that to some extent.

One more thing with a tax and transfer from the middle class to the middle class the dead weight loss is a total waste.

An example of a possessive externality from investment:

A man has a small mower and cuts grass for $30/yard. It takes him 5 hours to mow a yard. Another man invests in a big fast power mower hires the first guy for $10/hour and charges the customer $20 to mow the lawn. All three are better off 2 by an externality.

An example of a negative externality from consumption:

A bunch of rich people decide to fly around the world in private jets pushing up the price of petroleum. Somebody has to consume less petroleum.

@ Floccina

According to the General Aviation Manufacturers Association there were approximately 312,000 active general aviation aircraft worldwide ( as of 2005).

Needless to say, compared to the millions of cars right here in America consuming petroleum, I’d say that the detriment to the petroleum supply personal aircraft cause is negligible — especially when considering they are but a minority within the overall number of planes.

I don’t feel this needs further elaboration, so I’ll stop there.

Additionally, you didn’t really explain how saving is preferable to consumption. I’ve always understood that saving (in lieu of spending now for the prospect gain in the immediate future) may not necessarily be deleterious. It’s over-saving that causes negative effects (deadweight loss), and is deplored in reference to efficiency of an economy.

Although, on an individual basis, it may be more beneficial for someone to save in copious amounts (as nobody.really remarked in a prior post), stating that money in the bank is likened to that of “Self-insurance”, which “enables one to avoid the cost of other forms of insurance.”

Be well

@Floccina: Is it just me, or is there anybody else not too happy with such understanding of the term “externality”?

Wasn’t there something about “not transmitted through prices” in the definition, or is my memory failing me?

Can not help it, but want to bring a similar example of a “negative externality”:

An evil starving child in Somalia (or in some deprived area in the US even) decides to sneakingly consume a piece of bread which pushes the price of grain up and makes a beautiful (and extremely socially valuable) commodity investment idea less lucrative for an enlightened blog poster…

Dmitry: One last round perhaps? This is what I found inconsistent:

1) “The following points are based on the premise that it is fair and sensible to tax labor (wage) income…if our premise is that we need to tax fruits of labor in a consistent and fair manner and tax them only once we need to separate income created by a person’s labor and income generated by using past proceed that have already been taxed.”

+

2) “we recognize the distinction between risk premium and pure labor compensation”

=

3) “we do not see a reason to give risk taking and fruits thereof a preferential tax treatment compared to labor compensation”.

Why does #3 follow? It seemed to me your premise shifted, because you want to include investment risk premia in the tax base, because you believe not actively dis-incentivizing it = creating a “preferential treatment”. This might be a fair point on the consumption tax, since C and I are alternative uses of labor income, but your characterization of a similar trade-off between labor and investment risk doesn’t necessarily follow. To me you’re advocating the opposite in a double tax on (part of an) investment. As a general matter your view of creating preferences would seem to require you either to tax all other uses of income as well, or explain why (only) the “natural” level of risky investment (out of after-tax labor earnings) would otherwise be too high. Either position would seem to take you away from premise #1.

You do justify a specific exclusion for the risk-free component as “pure” time preference, but it seems to me that risk premia are also part of that required return for deferring consumption. E.g. you wouldn’t want to use a Treasury rate to PV a business project. (The “risk appetite” that demands additional payment for “volatility accepted” is one of aversion.) And I love David Friedman, but I think you and I agree that whether we call an index return “passive” or “pure risk-taking”, it is not labor. So it seems we’re left with quibbling over whether we should consider as a taxable return on labor/skill/luck (pretty indistinguishable in that context) the “excess return” over either a CAPM-type required return or an actual index return. (And the question remains then whether these gains should be offset by losses for those who underperform whatever standard we set.)

P.S. You make an interesting point that within labor compensation there may be premiums paid for factors related to safety (or stability for that matter). Not sure what the implications of that should be for a tax on labor income. But I think the index fund example proves that in general it’s not “virtually impossible to separate” returns to labor vs. *intertemporal* investment risk. And on the gambling issue, I was mainly just speculating on how people rationalize that distinction. To me the similarities with investing could lead one at least as easily to conclude that those earnings should not be taxed either, e.g. if it’s all just after-tax income changing hands (although I believe we do at least allow people to deduct some gambling losses).

Iceman: Sure, sorry for perhaps swamping you with too much text, I was merely coming back here waiting from some reaction from professor Landsburg to my original arguments and was inevitably tempted to reply to posts :) Thanks for letting me polish my argument,anyway!

Well, my argument the way you interpret it indeed looks quite clumsy, except that it is not really my argument :)

Let’s just use my original text and dissect it into statements and conclusion:

1.Any market investment return is a product of risk free rate, volatility accepted (i.e. risk appetite) and investment management work. + 2.Risk free rate should be except from tax (as per SL’s argument). While + 3. we recognize the distinction between risk premium and pure labor compensation + 4. we do not see a reason to give risk taking and fruits thereof a preferential tax treatment compared to labor compensation, = 5. so the only element qualifying for tax exemption is the risk-free rate.

You say my argument is inconsistent. I merely say that you just do not agree with my statement 4.

You have every right to do so, but as I 1.presume making a notional interest deduction is pretty straight-forward and I think 2. we agreed that separating risk from labor is often impossible, my question to you is:3. forgetting for a moment my objections to not taxing fruits of risk, how do you actually proceed with providing tax releif for risk while not affecting labor?

As we established separating fruits of labor from fruits of risk objectively is impossible as all, even most strait forward manual labor has some risk component to it, we have only 4 practical choices:

1. Keep taxing everything (all capital gains and all dividends) on the same basis as it is now

2. Not tax anything as per original SL’s argument

3. Exempting the risk free rate but taxing everything else (risk and labor) on an equal basis

4. Trying to establish the distinction between risk and labor in each case in some arbitrary manner (feel free to offer an objective and consistent approach) in order to give those two components different tax treatment.

Which one do you prefer?

I am not sure why do you seem to be unhappy with the concept of “preferential tax treatment”. If you tax one part of income (from labor) differently from another (from risk), the item that is taxed less is receiving a preferential tax treatment, no?

I am not claiming any trade-off between risk and labor (and thanks for reading my other posts :) ), I am just saying that if you propose taxing 2 parts of income differently, you probably should come up with a rationale. We do have it for a risk free rate – do we have it for a risk premium?

I can only repeat my previous counter-argument: Too much risk is likely to be more harmful to the society then too much labor, so why should risk have more tax incentives? (or less “active dis-incentives” if you prefer to put it).

You sure could say that it would be ideal not to tax either, and I would agree if you do, but that is departing from our first premise and is therefore best saved for another discussion.

I am sorry, the following bit I honestly could not understand despite re-reading several times. If you still want to bring this point, could you please parafrase somehow?

Your quote: “ To me you’re advocating the opposite in a double tax on (part of an) investment. As a general matter your view of creating preferences would seem to require you either to tax all other uses of income as well, or explain why (only) the “natural” level of risky investment (out of after-tax labor earnings) would otherwise be too high. Either position would seem to take you away from premise #1.”

I think the justification for exempting risk-free return has been sufficiently explained and we more or less agreed on it? The same is yet to be done for risk, if you wish.

“it seems to me that risk premia are also part of that required return for deferring consumption” – honestly I just can not agree. Any proofs for that? Do you imply that no-one is buying government bonds/bills (the closest material thing to a risk-free investment)? Or that if a completely risk-free bond should such a thing appear would have no market?

Most things on Earth are not perfect, so it is impossible to offer a completely risk-free rate and we use a closest possible approximation (for many years it has been US t-bills/t-bonds) and call it risk-free. So unless you are referring to that unavoidable risk of the least risky investments (which is already in our risk-free rate and not supposed to be taxed anyway), the very existence of the huge government bonds market undermines your statement.

As to your business project PV example – not to get distracted – well I would, and every bond trader does, if our business project is buying treasuries :)

“The “risk appetite” that demands additional payment for “volatility accepted” is one of aversion.” – well exactly, and risk aversion is the market equilibrium. Only certain separated enclosures for risk-seekers such as casinos effectively charge for allowing patrons to take risks (while arguably also providing entertainment for that money). In the rest of the market risk premiums are a norm and risk penalties are a rare exception.

Great that you love D. Friedman, he is a fine economist and son of a great father!

“So it seems we’re left with quibbling over whether we should consider as a taxable return on labor/skill/luck (pretty indistinguishable in that context) the “excess return” over either a CAPM-type required return or an actual index return.” – well, unless I misunderstand you here, no… I argue in favor of using risk-free rate (which is easily observable and equal for everyone) for deduction and you apparently prefer to use some unknown measure that compounds some portion of risk (it does not cover risk of lawsuits over fiduciary duty breaches to the investment manager, I suppose?) with the risk free rate.

So if you would like to have another last-last round on this, may I suggest that you first write what exactly do you propose to have on a tax form for capital gains for example?

My suggestion would be something like this: “ Please write write total proceeds from your asset sale in A. Now please write the initial amount of money invested in B. Now please apply the notional interest multipliers for all periods your money was invested (available on our website or in our office). Put the resulting amount in C. Now, subtract C from A and multiply it by D the tax rate – this is your tax to pay.”

What would be yours? (will it include words “please include the benchmark you feel is relevant”? :) )

And then if you prefer we can proceed to discuss why risks should be taxed less then labor (if this is still what you are suggesting).

Index fund example is only relevant as I previously mentioned for Investment managers confined by a specific investment mandate. I I am only allowed to invest money in NYSE-traded securities, in makes sense to assume my skill is deduced by comparing my returns with NYSE index fund returns. If i am allowed to invest where I want it makes no sense.

Dmitry (and others engaged in this conversation): I am traveling this week and have very little time to read and respond to long comments. Please don’t let my silence discourage you from continuing the conversation; I’ll catch up when I get back.

“2,3,4,5 and 6) The tax rates on dividends, interest, capital gains, corporate incomes and estates. I believe these tax rates should all be zero.”

I agree.

“That is not a statement about how progressive the tax system should be.”

You can’t have a tax that is more progressive than a flat tax and set these other rates to zero. The reason we have these other taxes is because we have progressive taxes. The taxes 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6 are there to prevent people from gaming the progressivity of the current system.

Dmitry – still there? Ok I’ll have one more for the road:

“if you propose taxing 2 parts of income differently, you probably should come up with a rationale.”

I thought you had already provided a rationale:

“if our premise is that we need to tax fruits of labor in a consistent and fair manner and tax them only once we need to separate income created by a person’s labor and income generated by using past proceed that have already been taxed.”

I agreed with that ‘initial premise’, which seemed to agree with SL’s argument about double taxation. I conclude from that that we shouldn’t tax investments (although some on this blog have given me a greater appreciation of the issue of income shifting). This also seems to answer your question:

“If you tax one part of income (from labor) differently from another (from risk), the item that is taxed less is receiving a preferential tax treatment, no?”

SL’s argument is that the investment income is not being taxed less, the effect on deferred consumption is purely incremental. In that context I feel pretty comfortable saying that double taxing something is punitive but not doing so is not preferential. The labor income is the source and investment is a use. Again, this is different from a consumption tax creating preferences among different uses of labor income (this is a virtue to those who think we need to encourage saving, but I generally prefer to keep the incentives neutral and otherwise stay out of the social engineering business).

You propose two possible rationale for taxing investments consistent with your initial premise of taxing labor income (only once):

1) D Friedman’s argument that investing can involve labor. However you agreed that investment risk premia are NOT a return to labor, and to me the argument is also undercut by the example of passive index funds (which most investors could choose and which by definition they underperform). That would seem to leave us at best with deciding whether and how to tax some notion of “super-excess return” purely attributable to extra “skilled labor”.

2) Since some labor income reflects embedded (‘direct’, ‘current’) occupational risks, we can’t disentangle labor from risk at all. To me this might be an interesting pragmatic argument for a consumption tax, but again we agreed that *intertemporal* investment risk and labor are conceptually distinct, and in my view they generally arise from pretty clearly separable activities (source vs. use). Again the index fund example (of pure risk with no labor) is helpful here.

Finally your discussion of risk premia vs. risk-free rate simply asserts that we should tax “risk-taking” without attempting to link this to labor income. You’re free to do that, but 1) I viewed it as a shift of premise, possibly reflecting a misplaced concern over “preferences” created from a tax on labor as discussed above; and 2) more importantly, you’re now required to address SL’s argument about double taxation (i.e. why it isn’t or why it’s not important).

P.S. On your distinction between the risk-free rate as “pure” time preference and risk premia as pure risk-taking, I also threw in the comment that one might view them as together constituting the required return (for a risk-averse investor) for deferring consumption in exchange for holding any asset other than a Treasury. E.g. I might (or might not) prefer a champagne bath today over the current paltry T-bill rate, but be willing to leave the bubbly corked for awhile to make you a loan at a higher rate (even if you offer all your blog posts as collateral). If this seems like semantics, that’s fine (and kinda my point) because I thought the whole issue was tangential anyway.

Iceman, sure I am still there. I regret to see that you’ve chosen to ignore my friendly challenge to provide your suggested wording for the tax form.

Although I am indeed easily tempted to write long reply posts, I think it would be helpful to first establish that we are discussing some real-life alternative to my suggestion and not just having an argument for argument’s sake. Please feel free to use the wording I suggested in my previous post as an example.

Once we have your exact suggestion it might help us eliminate further unnecessary repetition.

Dmitry – actually I proposed very simple wording for the form: capital gains rate = zero. My friendly challenge to you is to explain why your proposal doesn’t involve double taxation (since you seemed to want to avoid that result).

Iceman, sorry for late reply, I was traveling for a while. Thanks for your clarification.

As you said “… wouldn’t the average market return from a — purely passive — index fund be a more appropriate (risk-adjusted) benchmark for determining the labor/skill component than some (uniform?) “notional interest component”?” in your original post I was under impression that you were proposing something new and not just supporting Professor Landsburg’s original proposal.

As to your challenge – i think I have taken it by my very first post – sorry if you are still not convinced. I have never claimed that my proposal totally avoids double taxation in all possible senses. The same is true for any labor taxation (that taxes proceeds from your past investmens in education for example). What my proposal does is avoiding double taxation to the largest practical extent without giving tax relif to some forms of labor and risk taking.

Cool, glad we got it sorted (sorta). I thought you had endorsed a principle of no double taxation of fruits of labor, and personally I don’t think we want to discourage investment (again I don’t consider not double-taxing something as providing ‘relief’). I can see why you got the impression I was making a positive proposal around the risk benchmark thing, but I was really just trying to say even if we agreed on taxing non-labor, I thought your division of the required intertemporal return between rf and rp was a bit contrived.

Interesting point again about how labor can reflect returns to embedded ‘ex ante’ investment (as well as risk), although I think we’d agree there’s no practical way to sort that out (talk about a benchmarking problem). To me the separability of investments made ex post from labor proceeds is categorically different.