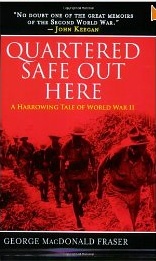

65 years ago today, the world changed. In his magnificent World War II memoir Quartered Safe Out Here, George McDonald Fraser looks back on what might have been:

65 years ago today, the world changed. In his magnificent World War II memoir Quartered Safe Out Here, George McDonald Fraser looks back on what might have been:

I led Nine Section for a time; leading or not, I was part of it. They were my mates, and to them I was bound by ties of duty, loyalty and honor… Could I say, yes, Grandarse or Nick or Forster were expendable, and should have died rather than the victims of Hiroshima? No, never. And the same goes for every Indian, American, Australian, African, Chinese and other soldier whose life was on the line in August, 1945. So [I’d have said]: drop the bomb.

…

And then I have another thought.

You see, I have a feeling that if—and I know it’s an impossible if—but if, on that sunny August morning, Nine Section had known all that we know now of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and could have been shown the effect of that bombing, and if some voice from on high had said: “There — that can end the war for you, if you want. But it doesn’t have to happen, the alternative is that the war, as you’ve known it, goes on to a normal victorious conclusion, which may take some time, and if the past is anything to go by, some of you won’t reach the end of the road. Anyway, Malaya’s down that way … it’s up to you”, I think I know what would have happened. They would have cried “Aw, fook that!”, with one voice, and then they would have sat about, snarling, and lapsed into silence, and then someone would have said heavily, “Aye, weel” and got to his feet, and been asked “W’eer th’ ‘ell you gan, then?”, and given no reply, and at last, the rest would have got up, too, gathering their gear with moaning and foul language and ill-tempered harking back to the long dirty bloody miles from the Imphal boxes to the Sittang Bend and the iniquity of having to do it again, slinging their rifles and bickering about who was to go on point, and “Ah’s aboot ‘ed it, me!” and “You, ye bugger, ye’re knackered afower ye start, you!”, and “We’ll a’ git killed!”, and then they would have been moving south. Because that is the kind of men they were.

I’ll add no comments, though yours, of course, are welcome.

[A hat tip to my Mom and Dad, who told me to read this book. So should you.]

Thanks Steve. Just ordered it. May I also suggest:

http://www.amazon.com/WAR-Sebastian-Junger/dp/0446556246/ref=sr_1_1?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1281098871&sr=1-1

Absolutely gripping account of the Afghan war. Finished it a couple of days ago and it’s still sitting with me.

Ok. Steven, read this book.

Well someone has to sound a sour note, so why not me. GMF is looking for an imprimatur for his opinion — now — that dropping the bomb was wrong. And he finds it in fabricated imaginings about his squad: see, they would have marched on rather than drop the bomb! My imaginings show it clearly!

A book I’ll pass on, thanks.

Ken B: I had originally planned to quote a much longer passage but hesitated because of intellectual property issues. It is quite clear from the longer passage that GMF is quite unsure of his own position re dropping the bomb, and that he’s running through multiple arguments in both directions with no clear conclusion.

Steven

Still the same rhetorical device though isn’t it? Fiction as argument. (Or perhaps you are conceding my point, just opining that the effect is less noxious in the full context.)

First of all, my wife is Japanese and had an Uncle who died instantly at Hiroshima.

But let’s play a little fiction.

Truman is running for re-election in 1948 and the war is finally over after suffering millions more casualties taking over Tokyo. The USSR controls all of Hokkaido.

Now, it is leaked that we had atomic bombs in the summer of 1945 that could have save millions of American lives and millions of Japanese lives. (My wife’s uncle was killed during the invasion of Honshu in 1946).

Did he do the right thing?

How would the election of 1948 look?

What would the history books say about Truman?

I don’t know if he did the right thing. He made a decision based on the information he had at the time. My gut tells me he made the right one.

PS My wife is 10,000% sure it was one of the worst decisions in history even if Japan wouldn’t have surrendered until Tokyo was invaded and millions more would have died.

I am always amazed that anyone can argue that we shouldn’t have bombed Hiroshima and Nagasaki. It was a war.

My neighbor was 19 at Omaha Beach, and 20 at the surrender of Germany. In August 1945 he was in Texas, practicing beach landings again. He is quite certain that many men in his unit wouldn’t have survived if we hadn’t dropped the bomb.

I feel for people who lost family to the bombings, but I don’t blame Truman. I blame Tojo and the military government that continued to fight when the war was obviously lost.

I just finished reading Winston Groom’s “1942”, which cites Japanese General Kawabe as stating that an Allied victory was inevitable after the Japanese abandoned Guadalcanal in early 1943.

As an aside, George MacDonald Fraser’s fiction work, particularly the Flashman series, is phenomenal (and very fun).

Steven – Not knowing GMF’s nationality, I read your dialogue as being in an Australian (or New Zealand) accent. Upon finding out that GMF was Scottish then re-reading your dialogue, I still think it’s more Australian than Scottish.

As to the content of your dialogue: I agree with Ken B — we have no way of knowing what soldiers on the ground would have preferred Truman to do. I can’t see how this in any way informs the 65 year old debate as to whether dropping the bombs was the right decision. Perhaps a better question is whether we (Americans, collectively) would support a proportional showing of force in the conflicts of our day. My sense is, given our current attitudes toward civilian casualties, we would not support it.

Some chilling facts to consider: Fighting for Iwo Jima, an island of 8 square miles, the US lost 6,800 men while the Japanese lost ~18,000 men (only 215 captured). When the Battle of Okinawa was lost the civilian population was urged to commit suicide by the Japanese military who warned them of soldier’s raping and torturing. The US military is still using the 500,000 Purple Hearts that they ordered when they were planning on invading Japan.

Applying the Amnesia Principle to a Japanese person in August 1945 applied to a random Japanese citizen:

Option A: The Americans continue bombing Japanese cities with fire bombs and then attempt a landing which will inflict massive casualties on the military and civilian populations. Moreover, if you live on the Northern Islands you will be subjected to 60 years of Soviet rule that will inhibit your standard of living. You’re chance of dying is ~10%.

Option B: The Americans drop two bombs instantly killing 75,000 people and eventually 246,000 from the acute effects. Many babies will suffer as a result of radiation poisoning and genetic mutations. Chance of dying <1%.

I think I would choose Option B all the way.

De-ontologically, is the use of atomic weapons inherently immoral?

In the Marine Corps leadership is defined as (1) accomplishment of the mission and (2) welfare of the men, in that order. Typically the second objective suffers because of the first. In the A-bomb scenario, both are maximized.

“I feel for people who lost family to the bombings, but I don’t blame Truman. I blame Tojo and the military government that continued to fight when the war was obviously lost.” – AI V.

“[If not for the atomic bombings] [t]he Americans continue bombing Japanese cities with fire bombs and then attempt a landing which will inflict massive casualties on the military and civilian populations.” -Diggle

The above quotes from other posters both imply that in the events leading up to the bombings, only Japan had the ability to change its course. The argument goes: The US was committed to an all-out “destruction of the Japanese forces”; since the Japanese had no way to defend them themselves against the US onslaught, they were foolish for not having surrendered sooner. My point is: Just because the US had “committed” to this onslaught in the events leading up to the bombings (e.g. through the Potsdam Declaration; through ordering 500,000 purple stars that were never used), doesn’t mean they had to follow through with it.

We can model the scenario using game theory. Japan moves first and has two possible moves: C. Continue fighting; or S. Surrender immediately. If Japan chooses C, the US can either: D. Destroy the Japanese military; or R. Retreat and defend the homeland from further attacks. If Japan chooses S, the US has no move. The payoffs (Japan, US) are as follows:

– Japan plays C, US plays D: (-1000, -1000), based on the relative magnitude of casualties

– Japan plays C, US plays R: (-10, -10), based on the relative magnitude of casualties

– Japan plays S: (-20, 0), where I assume that the -20 represents the psychic cost of the Japanese surrendering.

We analyze the game by working backwards. If Japan plays C, the US gets either -10 from choosing R or -1000 from choosing D. Clearly, the US prefers R when Japan plays C. In making their decision, the Japanese take into account that if they play C, the US will play R. Therefore, they compare their payoff of playing C, -10, to their payoff from playing S, -20. Clearly, Japan prefers C. Therefore, the equilibrium of the game has Japan continuing to fight and the US retreating and only defending its homeland from further attacks.

But we’re not done yet, since the US would not be happy with this outcome. The US would prefer if Japan chose S. Therefore, if they can convince Japan that they will play D if Japan plays C, then Japan will choose S (since -20 is better than -1000). How in practice can the US convince Japan that they will take measures that are clearly not in their own interests? By taking positions in favor of D that are difficult to back down from. By Truman giving every indication that the allies would not back down until the Japanese forces were completely destroyed, which would also lead to considerable destruction of the Japanese homeland, he was hoping to force Japan into choosing surrender. But when such rhetoric did not work, the US still had the opportunity to turn back.

The conversation that most of the posters on this blog prefer to engage in, regards how best to accomplish action D in the game above: by using atomic bombs or by continuing their bombing raids followed by a protracted land war. This strikes me as a misguided conversation since it completely ignores the fact that the US could have chosen some other course that would have led to fewer lives lost then either of those options. Then again, I am just a comic, not a war historian, so what do I know?

Another view, also from an author who was an infantryman in the war:

http://crossroads.alexanderpiela.com/files/Fussell_Thank_God_AB.pdf

I side with the droppers, for the well-known reasons. But if we’re going with counter-factuals: would the world have been better off if nuclear weapons had not been developed until at least several decades later, or not?

Joe, you must also take into account:

1. Cost to Japan of a Soviet attack.

2. Cost to China et al of a continued Japanese occupation.

3. Cost to everybody of a later Japanese breakout (cf Germany 1918, 1939).

Hey professor are you alright, you haven’t posted in a few days?

Bradley: I believe that following a recent court ruling, he has married one Paul K., and is now on a working honeymoon during which he will be debating the existence of the Poi Axioms in a Whites-only club. Or something like that.

We all wish him well.

Been away for a while, but just adding my $0.5 worth. Hiroshima was OK – morally justified to send a huge shock to Japan and bring the war to a fast conclusion. Nagasaki was not. I think the same effect could have been obtained by dropping the second bomb somewhere less populated, just to prove that Hiroshima was not a one-off.