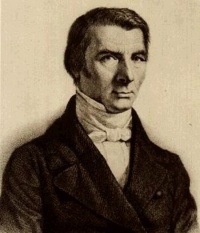

Today is the 209th birthday of Frederic Bastiat, the patron saint of economic communicators.

Today is the 209th birthday of Frederic Bastiat, the patron saint of economic communicators.

Of all the essays ever written, the one I most wish every voter could read and understand is Bastiat’s That Which is Seen and That Which is Not Seen. A boy breaks a window. Someone in the crowd observes that it’s all for the best—if windows weren’t occasionally broken, then glaziers would starve. This can’t be right, says Bastiat. If it were, we’d have no reason to diapprove of a glazier who pays boys to break windows. But why is it wrong? It’s wrong because it focuses on what is seen—six francs in the glazier’s pocket—and ignores what is unseen, namely the shoemaker who is deprived of a sale because those six francs come from what would have been the homeowner’s shoe budget.

Bastiat’s great insight in this essay is that exactly the same fallacy, in only slightly subtler form, underlies many of the public policy positions that were taken seriously in the 19th century—and, we might add, in the 21st.

The disbanding of troops (in Bastiat’s time) or a reduction in military procurement (in ours) is said to create great hardship for those who who sell bread to the troops, or parts and labor to the military contractors. It’s said that if we dismiss 100,000 unnecessary soldiers (or a 100,000 unnecessary workers), we’ll drive them into other industries where wages must fall. That’s what you see.

But what you do not see is this. You do not see that to dismiss a hundred thousand soldiers is not to do away with a hundred millions of money, but to return it to the tax-payers. You do not see that to throw a hundred thousand workers on the market, is to throw into it, at the same moment, the hundred millions of money needed to pay for their labour; that consequently, the same act which increases the supply of hands, increases also the demand; from which it follows, that your fear of a reduction of wages is unfounded. You do not see that, before the disbanding as well as after it, there are in the country a hundred millions of money corresponding with the hundred thousand men. That the whole difference consists in this: before the disbanding, the country gave the hundred millions to the hundred thousand men for doing nothing; and that after it, it pays them the same sum for working. You do not see, in short, that when a tax-payer gives his money either to a soldier in exchange for nothing, or to a worker in exchange for something, all the ultimate consequences of the circulation of this money are the same in the two cases; only, in the second case, the tax-payer receives something, in the former he receives nothing. The result is—a dead loss to the nation.

And on he goes, relentlessly applying the same observation to taxation, public support of the arts, trade restrictions, credit markets and more. Nobody has ever said it better or more accurately.

Edited to Add: Commenter Cloudesley Shovell observes that I appear to have gotten the date of Bastiat’s birthday wrong, but suggests that Bastiat is worth celebrating for the entire month of June. I regret the error and gratefully accept both the correction and the exit strategy.

*disapprove

would you do a post on Malthus?

Sources show that Bastiat was born on either the 29th or 30th of June, 1801, 209 years ago.

I say celebrate Bastiat and his scholarship for the entire month of June. He’s worth it.

In the case of the broken window, isn’t the shoemaker a bit of a red herring here? He stands for all the things the shopowner would have done with the 6 francs, so now we can just assume the glazier buys an extra pair of shoes instead, so the shoemaker is just as well off as before.

Compared to the situation where the window isn’t broken,the shoemaker is in exactly the same position; the shopowner has lost a pair of shoes and the glazier has gained a pair of shoes; but the glazier has also lost a pane of glass and the time spent installing it – that is the total loss to “society”.

I am with EricK here. Still, this is much closer to the truth than the people Bastiat was criticizing.

We shall make this Bastiat Month! I approve.

Bastiat is one of my dearest most favorite economic authors (perhaps an odd position for an admitted Keynesian?). I would add the Candlemakers petition to the required reading list, even before twisatwins.

I think that like Keynes, who is often misrepresented as advocating a large intrusive government with expanding claws into the economy, Bastiat is often portrayed, erroneously, as a market anarchist.

In truth Bastiat conceded the possibility that programs funded by taxes could yield greater benefits than their cost to the taxpayer. But only insisted that a propper assesment of that value be conducted (publicly) before those decisions are made, “All I say is, – if you wish to create an office, prove its utility.”–twisatwins, Bastiat

Of particular joy is the section of that work on the Theatre. But also keep in mind, that as Bastiat wrote his treatise on Laizze Fairre economics, there were tens of thousands of Frenchman starving or wasting to death (famine and disease, the two causes of deaths most often fixed by public spending, was the #1 cause of premature death in France). There was no recessions or depressions in his time because the unemployed had the good sense to starve to death.

Bastiat’s birthday may not be until June 30, but June 1 is the 260th anniversary of The Law’s publication. A noteworthy day in my book!

EricK has missed a trick here. Bastiat’s point with the cobbler is that the “stimulus” of the glass pane purchase is no stimulus at all just a redirection away from other uses.

“In the case of the broken window, isn’t the shoemaker a bit of a red herring here? He stands for all the things the shopowner would have done with the 6 francs, so now we can just assume the glazier buys an extra pair of shoes instead, so the shoemaker is just as well off as before.” – EricK

No, EricK, the point is that when the window gets broken society is one window poorer. The six francs could spent on the window to repair the broken one could have been spent on another window in a new house, or to buy a new pair of shoes, or to buy anything else for six francs.

This is along the same lines as the fools saying Katrina was good for New Orleans because it stimulated the contruction industry. By this logic it would be good for the government to bomb cities so they would have to rebuild.

Think of your own window. If your window was broken by some punk kid, would you be richer or poorer? You obviously would be poorer. Since the kid didn’t produce anything to replace your window in the act of breaking your window, society is one window poorer. If you think not, then consider this: while you’re at work I burn your whole house down. Now you are definitely poorer. By setting the fire I destroyed property, i.e., destroyed wealth, instead of creating it. But by your logic, society wouldn’t be one house poorer.

This of course makes no sense. The money spent to rebuild a house CANNOT be used to build a new house. So if your house cost $150K, then for another $150K there could be two houses. Instead, I burned your house down, so $300K was spent to build just one house.

Hope that clears things up.

Regards,

Ken

Ken -I don’t see why you are snarking at Erik; he was right, the shoemaker is not relevant.

Ken, I think you are in total agreement with Erick – it is not the shoemaker who loses, but as Erick said ” but the glazier has also lost a pane of glass and the time spent installing it – that is the total loss to “society”.

Steve, it is helpful for us non-experts to have these fallacies pointed out, and that we can address the real issues. I have heard this said of the trillions spent on thre Iraq war – “that can’t be right”, I thought. Here is why, explained clearly.

If we wish to promote Keynesian type economics, or execute a war, we must explain where the benefit comes from – it cannot come only from paying people.

What is absent from the analysis is whether the shopowner or glazier gets more utility from an extra “pair of shoes” (or whatever it is they would have spent the 6 francs on). Since people will put a different value on the same item, it is not clear that one can say the shopowner’s loss of a pair of shoes is exactly offset by the glazier’s gain of a pair.

thedifferentpill,

I like being snarky. I get a lot of pleasure from it, just as you derive pleasure from being a scold. And while your scolding me, you can scold EricK for being deliberately obtuse; his deliberate obtuseness led me to misunderstand his post. Of course in a general analysis the shoemaker is a red herring, but as anyone can tell you, talking to non-technical people, it’s ALWAYS good to have a concrete example. Steven chose the shoemaker. I think Steven’s intent with this blog is to be appropriate for as general consumer as possible.

Regards,

Ken

PS: snark!

Please note we are a blessed community and have two Kens. One is graced with a B one is not. Ken snarks because he wants a B and cannot have one.

Still the shoemaker is not a red herring. The premise of the broken window is a good thing argument is that the purchase of the new window spurs economic activity. But so would the purchase of new shoes. Or snarks could one purchase them.

KenB, if you look at the argument that way, the shoemaker might not be a red herring. But the argument could be rephrased this way:

The broken window is a good thing because now the glazier has money to spend which spurs economic activity.

To which the rebuttal is: But the shopowner had some money to spend, and so spur economic activity, but instead had to waste it on mending his window.

This, to me at any rate, seems clearer and highlights where the real loss is.

The trouble with bringing the shoemaker in is that both the shopowner and glazier need shoes.

Which I suppose leads on to how a stimulus is meant to work: Money is somehow transferred from people who wouldn’t spend it immediately to people who would. Or in this example, the glazier wants to buy shoes, but the shopowner doesn’t want to do anything with his money.

This may be the wrong thread to post this in but Chuck Schumer has proposed legislation to levy a tax on calls made by US customers which are routed to offshore call centres.

http://www.google.com/hostednews/ap/article/ALeqM5hxABQ3KHM3k1UW9C3P19UrY055pwD9G17V2O0

Schumer — THEY TOOK OUR JERRBS!!

Hello, Harold.

The benefit they might say about Keynesian actions is they trick people.

– Ryan

“Money is somehow transferred from people who wouldn’t spend it immediately to people who would” – EricK

Is this not what banks do? Don’t banks lend out savers’ money to spenders?

This is definitely not the same as government transfers, though, since banks lend money to people who are likely to pay that money back, thus replenishing the savers’ money. In other words, banks put unused money in the hands of producers to use that money productively. While government transfers go to everyone as a “tax credit”, or to the politically favored, to be spent however productively or non-productively as they want.

Ken,

Don’t the banks also loan money for unproductive things, like letting someone own a home?

-Ryan

All you need to argue here is that the shopkeeper can simply give the glazier 5 francs and everyone is better off. Breaking the window is just an inefficient way of effectuating the transfer.

Neil: Excellent observation. Thanks.

@ErikK To fix the broken window, the glazier must spend some of his own time and energy on materials and labor. His revenue is 6 francs, but his net income on the transaction is less than that, and so he actually has less than 6 francs to spend with the “shoemaker”. It is seen that the glazier is better off and the shopowner is worse off. What is not seen that the shoemaker is also worse off.

Neil– (or anyone who has been paying attention since last November).. An economist was raised as a topic on this blog (I think)and I read up on the guy but now cannot remember his name.

Who showed that any position along (or maybe within)the PPF can be maintained if transfer payments are employed? I swear it came up on this blog but now I cannot find it.

Anyway this is more-or-less what you are getting at I think. The window doesn’t need to break for the glazier to get enough money to eat. If the community values having a glazier, the same effect can be had without the economic loss of a broken window vis a vis transfer payments.

This sounds an awful lot like Pigou. The father of welfare capitalism maybe?

Benkyou:

Who showed that any position along (or maybe within)the PPF can be maintained if transfer payments are employed? I swear it came up on this blog but now I cannot find it.

This is known as the Second Fundamental Theorem of Welfare Economics. It holds under a great variety of assumptions, and is due to different people under different assumptions. My history is a little hazy but I suspect the first rigorous version is due to Walras.

TYVM. I have a feeling I have a book on both the subject and the man somewhere I’ll dig it up.

It does kinda sound like Pigou though. But I think I’m thinking out of time.