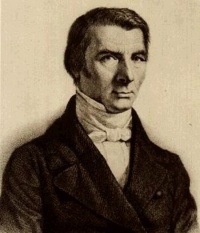

A month ago, I prematurely celebrated the 209th birthday of the great economic communicator Frederic Bastiat. Today (unless I’ve screwed up a second time) is actually his birthday. A good way to celebrate is to read (or reread!) Bastiat’s little masterpiece Economic Sophisms; you will never see the world the same way again. Here’s a taste:

A month ago, I prematurely celebrated the 209th birthday of the great economic communicator Frederic Bastiat. Today (unless I’ve screwed up a second time) is actually his birthday. A good way to celebrate is to read (or reread!) Bastiat’s little masterpiece Economic Sophisms; you will never see the world the same way again. Here’s a taste:

At a time when everyone is trying to find a way of reducing the costs of transportation; when, in order to realize these economies, highways are being graded, rivers are being canalized, steamboats are being improved, and Paris is being connected with all our frontiers by a network of railroads and by atmospheric, hydraulic, pneumatic, electric, and other traction systems; when, in short, I believe that everyone is zealously and sincerely seeking the solution of the problem of reducing as much as possible the difference between the prices of commodities in the places where they are produced and their prices in the places where they are consumed; I should consider myself failing in my duty toward my country, toward my age, and toward myself, if I any longer kept secret the wonderful discovery I have just made.