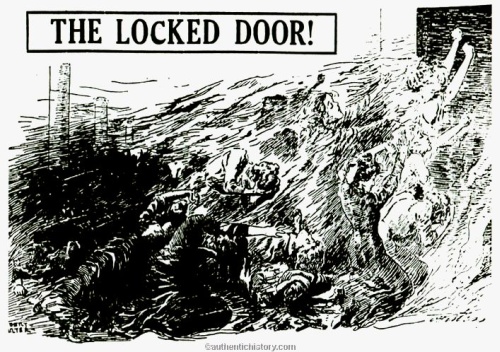

Today is the ninety-ninth anniversary of the legendary fire at the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory, which reigned for ninety years as the worst workplace disaster in New York history. A hundred and forty six workers died that day, most of them young women. Escape routes were cut off by doors that were kept locked to prevent employee pilfering. The main exit from the factory floor was designed so that only one person at a time could pass through; departing workers had their handbags inspected by a night watchman. “It comes down to dollars and cents against human life, no matter how you look at it”, in the words of then-Fire Chief Edward Croker.

Well, yes, of course it comes down, at least in part, to dollars and cents against human life (where “dollars and cents” are, of course, stand-ins for “a whole lot of other things we care about”). The interesting question is whether the terms of trade were favorable. In other words: If the workers, in advance of the fire, had been fully informed of all the risks and all the potential consequences, would they have wanted those doors locked or open? Or more generally: When the New York state legislature responded to the fire with over two dozen new occupational health and safety laws, were they compounding the disaster?

I propose to take the question seriously. Would the workers have preferred to have working fire exits?

It helps to know that the labor market in the garment industry was highly competitive on both the supply and demand sides. There were hundreds of garment factories in lower New York, some of them in the same building as the Triangle factory. (The fire was confined to Triangle’s three floors.) They drew their workers from the teeming tenements of the Lower East Side, both as direct employees and through independent contractors. In a competitive labor market, workers are paid their marginal product. (For this there is ample theory and evidence, which no economist disputes.) This means that if one additional seamstress can add six dollars a week to the company’s revenue, then all seamstresses of that skill level are paid six dollars a week. (Six dollars a week is a historically accurate wage rate.)

Now let’s suppose that in the presence of open doors, the typical employee pilfers two blouses a week, with a wholesale value of 60 cents apiece. (Sixty cents is a guestimate based on the retail price of a little over a dollar, which I found in an old Sears catalogue. Two pilfered blouses a week is a number that I just made up. If you don’t like that number, feel free to adjust my calculations.) The employee’s marginal product falls by $1.20, so competitive pressures force the wage to fall by $1.20 as well. That’s a 20% wage cut (though it’s partly offset by the pleasure of having a very full clothes closet and an infinite supply of rags).

Now our question becomes: Would a worker, given the choice and fully recognizing the risk of fire, have taken a 20% wage cut in order to keep the exit doors unlocked?

Well—would you take a 20% wage cut in order to keep the exit doors at your workplace unlocked? (I know, I know, they’re already unlocked—-but pretend they’re not). I wouldn’t. Of course this proves little, because you and I live in a very different world than a 1911 garment worker. But the differences cut both ways. On the one hand, the garment worker occupied a wooden building filled with fabric and tissue paper. That makes the exit door more valuable. On the other hand, the garment worker was a lot closer to starvation than we are. That makes the wage cut harder to swallow.

My guess is that the second effect is bigger, but I could be wrong. It might not be too hard to resolve the matter with a little effort, a little arithmetic, and a little bit of data on how the demand for safety varies with income. In any event, I’m extremely skeptical that our desperately poor garment worker would have chosen the wage cut.

What other evidence speaks to the preferences of the workers?

In one direction, there is no pre-fire record of workers offering to take wage cuts in exchange for better fire safety, or of firms anticipating that they could cut their wage bills by putting in better fire doors. There was plenty of labor unrest, but so far as I am aware, it was almost all about wages and hours, not safety. The most straightforward reading is that workers preferred higher wages to more safety, but an alternative reading is that workers were blissfully unaware of the extent of the fire risk.

But in the other direction, there is an extensive post-fire record of workers applauding the new safety regulations, despite the fact that the regulations must have depressed wages. The most straightforward reading is that workers preferred more safety to higher wages, but an alternative reading is that workers were blissfully unaware of how the new laws would affect their wages. Another alternative reading is that pilfering was never the major problem I’ve been envisioning, so the effect on wages was minimal. (It’s hard to measure the effect directly because wages change for many other reasons as well.)

Bottom line: I can’t be sure (and I’ve pointed out several reasons I might be wrong), but I’m guessing that no 1911 garment worker would have wanted to work in a factory with unlocked exit doors. If I’m right, they got the mix of risk and income they’d have chosen. The fire was tragic but the market worked.

Isn’t the best way to determine this sort of preference by finding out, in what you describe as a highly competitive environment on both the demand and supply side, whether it was common or uncommon for doors to be routinely locked during working hours in such employment? If jobs for workers included both places with locks that paid more and places without locks that paid less, and both filled, doesn’t it follow that workers were largely indifferent in general and gravitated to the trade-off they preferred? It would then follow that those who were unfortunately trapped in the fire at least were there because they made the choice that ex ante was right for them.

How much did average wages drop following those legally mandated safety requirements?

You say that the wage cut would be partially offset by having a full clothes closet. Isn’t it actually the case that a wage cut of $1.20 is more than offset by having 2 blouses which can be sold for a $1 each and workplace safety?

The answer is “Mu”.

Find another way to stop employee pilfering.

RL: This is a good method but an imperfect one, since workers might have been ill-informed about fire risks, and we want to know what they’d have chosen if they were well-informed.

EricK: You assume the employees have access to customers who will pay $1 each for those blouses. Unfortunately, if that’s true, it encourages even *more* pilfering. Employees will continue to pilfer as long as their swag has any value at all to them; this includes blouses that are destined directly for the rag bin.

This article reminds me of the Ford Pinto http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ford_Pinto where Ford decided to pay for the potential law suits rather than fix the problem.

Here is my initial take: If there were factories that had open doors with lower wages, then one would expect a separation of dishonest workers taking the lower wages with pilfering privileges, while honest workers (with low fear of fire) to take the high-pay, locked door jobs. If pilfering was too much for open-door firms to survive (average pilfer greater than $6) in your example, then open doors could not survive, and all worker types would be pooled in the locked-door firms. If locked door firms were the only kind in NY at the time, then their ability to hire workers means that those jobs were viewed as better than some other non-garment alternative.

I would suppose, though, that there would have been lower cost ways of controlling theft, while allowing for rapid fire exiting. For example, exit doors with alarms would make it hard to skip the front door bag search without drawing attention to the theft on a regular day. If there was a genuine fire, though, people could stream out of those doors. Or absent fire exits with alarms, a rule could be implemented that anyone who does not exit through the front door bag check would be immediately fired. Then, anyone could only steal one armload of stuff once before being missed at the front door and being fired. Regardless, I suspect that the garment firms figured out a fairly low cost alternative to the locked door policy.

Steve: To a first approximation, the amount of pilfering would be equal to the amount of clothes the person wanted plus the amount they felt they could sell. Unless, that is, you think people are prepared to take the risk of stealing even more stuff (and no doubt losing their job and freedom if caught) just for the hell of it.

What seems more likely is that people desperate for work do not bother to check whether fire doors in their prospective place of work are locked, so are not making their choices based even partly on that criterion. What seems equally likely is that the factory owners had found a cost-free way to reduce whatever pilfering there was, and as such probably didn’t even care how much pilfering there was, because locking the doors always showed a gain even if the pilfering rate was 1 blouse per factory per year.

The main reason the workers were in a factory in the first place was “worker protection” laws barring many kinds of work at home. Many women garment workers with children preferred to work at home so they could watch the kids, but this was outlawed. Irving Howe’s “World of Our Fathers” is a fascinating book, largely because Howe, a lifelong socialist and a terrific reporter, documents the vast harm done to workers by legislation advertised as “protecting” them without ever seeming even to consider the possibility that leaving people to work out their own arrangements might be a good idea.

Many of these laws are still in force, and they still do harm (for example, to skilled workers with physical handicaps, to women with children, and by forcing commutes on people).

Is it true that in a competitive market the employee is paid the marginal product, or just in a perfect market? Does “competitive” in this context mean “perfect”? The distinction is important. It is said that “no economist disputes this” – I would like re-assurance that this is true for real-world situations.

As Steve has said, the arguments may be finely balanced. I think the pilfering would be less than he suggests, as there would be other dis-incentives introduced, as EricK says. The argument remains that increasing the safety has a cost in increased pilfering, which must come from somewhere. The competitive market model indicates this must come from the wages because the marginal product of the employee is reduced, but if the market is not quite perfect, then it could come from somewhere else.

A slightly different point is the effect of time. It has been mentioned elsewhere that measuring wealth is only appropriate on a whole-life basis as there are ups and downs. The effect of legislation opening the doors may produce a short-term disadvantage, but over time produce a significant benefit.

The market is highly competitive. This presumably means that the employer cannot raise prices as there are other factories selling at a lower price. He only makes the minimum profit he is prepared to work for. He cannot raise wages, as the cost cannot be passed on. However, if the cost is imposed across the whole industry through legislation, then all factories face the same costs, and all factories must raise prices. The customer must pay more for their shirts. It is more like a rise in the price of cotton, which affects everyone and must be passed on or go out of business. The customer pays for the pilfering, as long as it is imposed universally.

If the employee is an informed rational being, why do they pilfer shirts which will cost them $1.20 in wages, when they derive less than this in benefit? One would think the employees themselves would be pretty good at spotting pilfering among themselves and be self-policing. You are offering them a choice of open doors or lower wages. If they are truly informed, they can have open doors and keep the wages. Why would they not choose this? This is perhaps summed up in the belief that it is wrong to steal, thus many will not pilfer even if the opportunity arises.

Of course, the workers are not informed, nor entirely rational. If you go shopping when hungry, you buy more stuff, particularly the stuff you fancy then and there, whereas rationality tells you to buy the stuff you will want in the future. If you are hungry all the time, you always buy more stuff you fancy then and there, such as wages, when it may be more rational to buy a bit more safety.

So overall, I would say that the pilfering costs may rise a tiny bit, but not to anywhere near 20% of turnover. The costs of preventing pilfering also rise a bit. This cost is universal, so can be passed on to the customer. The customer has a bit less to spend on other things, but the increased safety costs are borne by everyone.

Another way perhaps is to let the factory owner decide, by making him pay full compensation if deaths arise in his factory. This method fails if he does not have sufficient funds.

Out of interest, what took its place 90 years later? Does this tell us anything usefull?

A sound analysis for the most part but you fall for a false dichotomy. Even without the modern technology that allows alarmed fire doors, surely there existed some alternative way to limit employee theft besides locking all the doors.

Fire is one of those rare events that humans are notoriously poor at weighing the danger of, and lost wages due to regulation are one of those matters of the unseen that only economists can see. So I think the obvious answers to both “why didn’t employees demand more safety” and “why did employees cheer the post-fire safety regulations” is your “blissfully unaware” option. However that does not allow us to conclude that locked doors were optimal.

Harold: Ninety years later, two airplanes flew into the World Trade Center.

Let me go back to EricK’s first point, and assert that, in any case, the figure we should be looking at isn’t $1.20 but $1.20 minus the value of the two blouses, which is likely to be noticeably less. You get to add on, though, rent-seeking costs — both by the company trying to deter theft, and by the women engaging in it — and something associated with the risk and inefficiency associated with the fact that the theft will be irregular (as opposed to taking part of the wages in the form of 2 blouses every single week).

You are assuming that the workers would steal blouses worth 20% of their wages. Why? Do you steal 20% of yours?

Harold:

The market is highly competitive. This presumably means that the employer cannot raise prices as there are other factories selling at a lower price. He only makes the minimum profit he is prepared to work for. He cannot raise wages, as the cost cannot be passed on. However, if the cost is imposed across the whole industry through legislation, then all factories face the same costs, and all factories must raise prices. The customer must pay more for their shirts. It is more like a rise in the price of cotton, which affects everyone and must be passed on or go out of business. The customer pays for the pilfering, as long as it is imposed universally.

This is correct (and very well put!) for as far as it goes. We should add this: First, the industry shrinks, because customers buy fewer garments at the higher price. Therefore many garment workers lose their jobs. There are now two possible scenarios:

Scenario I: It’s easy to move to other industries. Let’s suppose it’s a safer industry, and that workers value this safety at a dollar a week. Then a) wages in those other industries must be a dollar lower than in the garment industry; b) nothing has happened to change wages in those other industries (assuming the number of displaced garment workers is small relative to the entire labor force); c) the garment industry wage falls to match the wage elsewhere; d) the garment industry now looks just like all the other industries that workers could have chosen to work in all along, so you’ve failed to offer them any options that they didn’t already have.

Scenario II: It’s not easy to move to other industries. Then, assuming the cost of fire escapes (to the employer) is greater than their value (to the employee), the wage rate falls by some amount in between the cost and the value. This leaves employees worse off.

>Now our question becomes: Would a worker, given the choice and fully

>recognizing the risk of fire, have taken a 20% wage cut in order to

>keep the exit doors unlocked?

How can you take this question seriously, you must know that humans are incapable ( including you ) to fully recognize and understand/appreciate risk ?

T.

Shouldn’t the regulations after the fire be viewed as an imposition of the preferences of more cautious, less hungry workers onto the less cautious, more hungry workers? That would explain why many post-fire workers would have applauded the regulations, even though they were bad for workers overall. The event may simply signify the time in history at which the safety-loving group became large or powerful enough to influence the government to pass laws in their favor.

I think a good solution would have been to put a key to the locked fire door inside a glass box beside a hammer. Under ordinary circumstances, I doubt a worker would be able to quietly break the glass and get outside while stealing some blouses, but in case of a fire I doubt they’d think twice before breaking it and getting out of there. Or perhaps people in the 1910s were just much more brazen in their theft than I imagine.

Tjd: at the margin, a 20% pay cut might mean starving to death within a month.

Given a choice between almost certain death in a short period of time, or being paid a wage with some unknown level of risk of being burned alive, as horrible as that set of choices might be, I think most people would choose the latter.

Thanks Steve, the shrinkage of the industry imposes the cost on the workers, one way or another, so we can’t get rid of it.

This leaves us the issue of is the cost worth it? There are other methods to reduce pilfering, and I and several commenters seem to think your estimate of the pilfering rate is too high. Nonetheless, we can assume that the new methods will be less effective, and / or cost a bit more. There is therefore some cost in terms of the wages for the increased safety. I would suggest it is way less than the 20% suggested, but the principle is the same. You say:

“Now our question becomes: Would a worker, given the choice and fully recognizing the risk of fire, have taken a 20% wage cut in order to keep the exit doors unlocked?” I agree that the worker would probably not take the 20% cut. I have argued that this 20% was much lower – say 5%, 2%? Take your pick. The lower the figure the more likely the answer is to be Yes, so they got a good deal with the enforced safety, and the market didn’t work. The figure you pick here involves quite a lot of gueswork, so you can argue either way, both about the level of cost and at what point it becomes worth it.

But that leaves a more fundamental question. The market should provide the optimum outcome, which is surely no pilfering and open doors? The cost to the general wage pool is $0.60 per stolen blouse. If the workers can’t get more than this by selling them (as they do not have accesss to the market), the overall cost to the workers is more than the benefit of stealing. Of course, the cost is borne by all workers, and the benefit all goes to the thief, so there is still an incentive to steal, but you should have to keep it secret from your co-workers as well as the employer. I think this would keep pilfering at a very low level. Either the pilfering level was way higher than the “market rate”, or the locked doors were costing way too much in terms of reduced safety.

Paul Grayson: Yes, your story seems exactly right as long as there is significant heterogeneity among the workers.

I suppose that’s true if you ignore the post-Keynesians, the Sraffians/neo-Ricardians, and the Cambridge Capital Controversy. Other than that, I suppose you’re right.

What a terrible tragedy. I’m guessing the potential cost of locking the doors was underestimated because of the inability to forsee and evaluate all possible outcomes. It is like the “too few” lifeboats on the Titanic. And every such tragedy is followed by a close-the-barn-door-after over-reaction.

So basically: How can it be okay to not hire a young woman but not okay to hire her and then put her to work in an incredibly dangerous work environment – Given that the young women in question would presumably prefer to have a dangerous job than be unemployed?

Right?

Nothing at all as long as there is full disclosure. As long as those women had full access to all of the relevant information and the tools to properly assess risk. But that wasn’t even remotely the case here. The workers were uneducated and cowed by social norms to not ask questions. Any argument that they understood the risk of fire is delusional.

It comes down to, “If they were too dumb or timid to ask the right questions then they deserve what they got.” Which would be just as good a rational for employing toddlers as landmine sweepers.

Terrible tragedy indeed. However, there was none as terrible until 90 years later (that incident I somehow overlooked!). I don’t know the dozen or so laws brought in in the aftermath, but the case that the one requiring unlocked fire doors is an over-reaction is far from made. It has prevented a repeat, and I can’t help thinking that the overall cost has not been that great.

Harold,

I did not mean to imply that the safety laws you mention are an over-reaction. Actually, I had in my mind the response to 9/11 which led Americans to surrender their precious liberties in the name of homeland security.

You state that there was a potential tradeoff between $6 per week and locked doors and $4.50 per week plus two shirts (on average) and unlocked doors. However, this isn’t necessarily the case. Suppose the mindset of the average employee is “all I see is that I am making a lower wage than the guy next door. I’m going to take some stuff to make up for the difference.” (I am of course assuming that shrinkage is very hard to catch without locked doors.) But if the employees don’t value each additional shirt as much as it costs the company, they are going to take more than $1.50 of shirts each week. This is going to cause the company to have to lower wages even more. But if the employees are still trying to make the situation worth their while, this pay cut induces more shrinkage. This creates a vicious cycle that is likely not sustainable. If this is the case, the only option that can persist is to lock the doors.

Like you said in the title, there are three sides to the story. :)

Economists Do it with Models. (Don’t I wish.) Doesn’t this violate the law of one price? After costs, the pilferers should be able to sell the products at the same price as the retailers, which is equal to the value of the marginal product, which is their wage.

After this post, I discovered the emergency doors in my work building are locked (at least on my floor). This is for the sake of keeping energy costs down by only using one set of doors. Would I take a 20% pay cut to unlock those doors? No. Would I take a 10% cut? Doubt it. Of course, I think the fire likelihood is quite lower than it would be in a 1910 factory.

Neil: I agree, I wouldn’t be surprised if some of the dozen laws brought in in 1911 were over-reaction, just not this particular one (in my opinion). There is a knee-jerk response to these kind of events “It must never happen again!” In the hysteria, the costs of the measures are neglected. I think it is part of our inability to properly asses risk. Rare events appear in our consciuosness as “never happens”, so we under-estimate the risk. Then one does happen, it gets saturation media coverage, it leaps up in our consciousness to “almost inevitable”, and we then over-estimate the risk. The question “is the legislation requiring unlocking fire-doors worth the cost?” is a valid question, and we must have some way to attempt to get an answer. The same questions should be asked of the post 9/11 legislation.

Sprobert – what percentage of your wages are represented by the energy saved by locking the door? This is compared to, say, putting a sign up saying “Please Do No Use This Door except In an Emergency”? The average powewr consumption of Sun employeees was 260kWh / year, at $0.1 / kWh = $26. This includes all power, so assume heating / cooling was half of this, = $13 / yr. Perhaps the extra opening and closing of the doors may use 10% of this (probably over-estimated), or $1.3 / yr. The average income is about $80000 / yr, so it would cost you not 20% pay cut, but 0.0016% pay cut to have the fire doors unlocked. I think its a bargain.

Harold,

You articulated, and very well, just what I was trying to say (and failed) about the way we assess some risks.

Neil hints at something that is a common problem in our society, that Steve has talked about before. We’re better at evaluating the advantage of something with a low value and high probability than we are of something with a high cost and low probability. If I plan on working at Triangle Shirtwaist for 5 years, and profiting $1.50 per week, the value to me is 5 * 50 * $1.50 = $375. If I value my life at, say, $20,000, then if the risk of my death is greater than 2% I should want to protect my life by unlocking the doors. However, we’re not very strong at making this comparative evaluation.

I see this as similar to the exclusion of abortion coverage from the new U.S. Health Care bill. Anyone participating in a subsidized plan must pay for abortion coverage under a separate, unsubsidized plan. It seems to me unlikely that a person would pay monthly for abortion coverage, because they would have to undertake a similar comparison – a known monthly payment vs. the risk of a high cost, low probability unplanned pregnancy.

@ Neil: Your comment relies on a number of implicit assumptions: 1. that the workers have the same access to the market as the company, which isn’t likely if for no other reason that I’m not going to pay the same price for a shirt sold out of a box on Canal Street that I would at a legitimate store. Granted, the workers would only have to recover the wholesale rather than the retail price of the shirt in order to be in line with marginal product, but we’re also getting into opportunity cost of time territory with the selling. 2. that trying to sell the shirts doesn’t markedly increase the probability of them getting busted for stealing, and 3. that they aren’t stealing and selling enough to push down the market price of the shirts. I doubt that all of these assumptions would have held in practice, which is why I went with the stealing mostly for personal use scenario.

I have been thinking about the point that the workers would be stealing from eachother. I think that if the picture portrayed is corrrect, with large numbers of small firms making modest profits, then the level of pilfering would be low. On this sort of scale it is easy to perceive that theft from the business comes out of wages to some extent. If the workers see the owner not apparently making excessive profits, as evidenced by a lifestyle not too excessively grander than their own, then it can be appreciated without understanding of economics, that the cost of the pilfering is going to have to come from the wages of people you know quite well. The worker can appreciate that the owner is paying as much as he can reasonably afford. I believe the motivation to steal will be quite low.

I believe that the motivation to steal will rise only when the scenario changes into a less that perfect competition one. For example, very large factories with some degree of monopoly power. The workers are not all known to eachother, the profits can be more than “normal”. The workers see a lavish lifestyle of the owners and do not know the workers from whom they are stealing. They perceive correctly that the costs could come from reduced profits. Motivation to steal becomes high.

The scenario described in the Triangle Shirtwaist is one of many small firms with apparently normal competition. According to my ramblings, the level of pilfering would be low. In order for it to be high, I suggest there would need to be some other distorting factor in the market to result in excessive profits, and the perception that the workers were not stealing from eachother, but “the boss”. As far as I know, we don’t have any actual data on the level of pilfering, before or after the tragedy. There may exist data on pilfering and relative firm size, which would go some way towards evidence for my hypothesis.

This is all wild speculation at the moment, I will think on it some more.

Steve,

“In a competitive labor market, workers are paid their marginal product. (For this there is ample theory and evidence, which no economist disputes.)”

Can you supply a good source that shows this empirically? I’m quite certain is MUST be correct. I’ve attempted recently to explain this to a skeptical friend, over his objections that “employers always want to depress wages below the true market value.” I was unable to convince him that they CAN’T do this; depressed wages obviously chase away workers. Some actual data might help.

GregS: The first thing that comes to mind is the near constancy of labor’s share of national income, which has been roughly 70% for well over 50 years. This is what you’d expect in a competitive abor market with Cobb-Douglas production (so it confirms a hypothesis considerably stronger than just “workers are paid their marginal product”) and it’s hard to see what else could explain it.

Professor Landsburg — I’ve enjoyed your full-baked Slate columns, and wish you the best of luck in trying to grow this half-baked blog post into something worthy of publication. But first please engage your own academic team to research this.

A few Google searches will point you in the direction of David Von Drehle, who wrote a 2004 book “Triangle: The Fire That Changed America.” Enough of the book is available via Google Books preview, in case you don’t have ready access to it at the Rochester library. It explains that it was never fully known whether the 2nd door was in fact locked. This is important because the judge in the criminal trial instructed the jury that the owners could only be convicted if they knew that the door was locked at that time. And, in fact, conflicting testimony was given at the trial. The law at the time had called for all doors to be unlocked.

Your whole analysis falls to pieces when you assign agency to the workers here. You completely forget that the factory owners, if they were rational economic actors, would have calculated the calamitous effects of a criminal conviction for negligence, or civil recompense to the families of the victims.

As it happened, the jury had enough of a reasonable doubt that the owners had cognizance of the doors being locked at the time of the fire, and they were acquitted. But they were open to civil suits, and ultimately had to pay $75 per victim. I don’t know the amounts of comparative suits in those days, but 10 weeks salary is slim by today’s standards. Let’s face it: any rational actor in society with a fair system of civil and criminal law must make decisions to reduce their exposure to punishment.

Your conclusion is thus under-informed and patently “I’m guessing that no 1911 garment worker would have wanted to work in a factory with unlocked exit doors.” You should have researched New York State law in 1911: “All doors leading in or to any such factory shall be constructed as to open outwardly, where practicable, and shall not be locked, bolted, or fastened during working hours.” A Google search will bring you references to this law from the literature.

And to *thus* conclude that “the market worked” after such half-assed research on your part is painfully heartless. (I appear to have done more research while watching the NCAA basketball today).

GregS:

At the micro level, see a paper by Hellerstein, Neumark and Troske in the Journal of Labor Economics, July 1999. They examine differentials between wages and marginal productivities using plant level data and find only one example where there is significant divergence.

Divergence does not disprove the theory because there may be other factors that cannot be fully accounted for, such as when workers are paid partly in job amenities.

Big picture: The article is distasteful. People died. Line up all the evidence you want and I’ll still deny the callous assertion that ‘The market worked’.

Fine print: The statement ‘In a competitive labor market, workers are paid their marginal product’ is tautological — being paid marginal product is essentially the DEFINITION of a competitive market. The author’s assertion that there is ‘ample evidence’ of the statement is therefore ignorant.

@ Jon: I do see what you are saying about the factual inaccuracy of the article. That said, I am not convinced that it changes the model of the decision process at hand- if anything, I would argue that the laws being as they were tip the tradeoff in a counterintuitive way toward the higher pay and locked doors. From what you are saying, law-abiding companies would have to accept the possibility of theft and discount workers’ pay accordingly, so there is still no way for the workers to get $6 per week and unlocked doors. Their choice, given the legal setup, is then $4.50 a week and unlocked doors or $6 a week with locked doors and potential remuneration should anything go wrong. If I was on the fence previously, this would tip the scale for me as a worker toward the locked doors. However, from the employer perspective, it should have the opposite effect.

@ G: I take objection to your claim that this article is distateful. People make risk-reward decisions regarding potentially dangerous fields of employment (coal miners, fighter pilots, etc.) all the time. Sometimes the outcomes of these decisions end up on the bad side of the coin- that’s just reality. Isn’t it better to study and try to understand those choices and tradeoffs in order to learn how make the best decisions possible rather than just pretend that the tradeoffs don’t exist?

Steve: “The first thing that comes to mind is the near constancy of labor’s share of national income, which has been roughly 70% for well over 50 years”

In the last 50 years there has been strong and enforced regulations – was this also the case in earlier times, and in other places?

Neil – I can only see the abstract of the paper you mention, but the one example they pick out there is women, which is quite a big sector. “Divergence” of 50% of the population seems to blow a bit of a hole in the theory. That women are paid less than men for similar jobs is well documented. The “marginal product” theory can only explain this if women have lower productivity, or are paid in employment “amenities”. I find these explanations somewhat unsatisfying. I am sure this must have been extensively studied.

Jodi: the article (um, blog post) is distateful to me as well since Professor Landsburg has failed to do the research, and thus concludes that “the market worked” based on a scant amount of inputs.

Either the cost-of-life is an input to his formula (and he omitted it), or it is the output of the formula. In the latter case, it would be useful to compare this across different industries. If some economist is toiling away at this, well then the well-read Steven Landsburg should direct his readers to him or her. Or if no one is doing this, it represents an opportunity for research…

Jon

Jon Garfunkel: This is absolutely back-of-the-envelope stuff, as I think I stressed pretty clearly. I think back-of-the-envelope skills are worth having, and that this was a useful exercise.

Harold,

In the paper, the authors use marginal productivity theory to identify instances of wage discrimination. (Women do not constitute 50% of the work force in the sample, BTW, nor do women’s wages differ from MP in all instances.) The authors find that the marginal product of women in the sample is lower than the marginal product of men, but that the wage paid to some women is lower by more than can be accounted for by their lower marginal product. In others cases, marginal productivity does a good job of explaining wages.

In economics, the marginal productivity theory is a powerful way of understanding wages and wage differentials, as Steve said. I think even Steve would agree that MP theory does not require that everywhere and everytime wages must equal MP, but we can think of no more powerful theory for understanding wages than MP.

Neil, yes, I was being a bit tongue-in cheek, as I hadn’t read the whole paper – it just seemed to leap out from the abstract. I am sure that the MP theory offers a good basis for understanding wages and has a lot of truth in it. However, it is not the whole explanation, as the situations where it does not apply can demonstrate.