Paul Krugman, apparently relying on the stupidity of his readers, opens with this quote:

“At some point, Washington has to deal with its spending problem,” Speaker John A. Boehner of Ohio said Wednesday. “I’ve watched them kick this can down the road for 22 years since I’ve been here. I’ve had enough of it. It’s time to act.”

Then Krugman comments as follows:

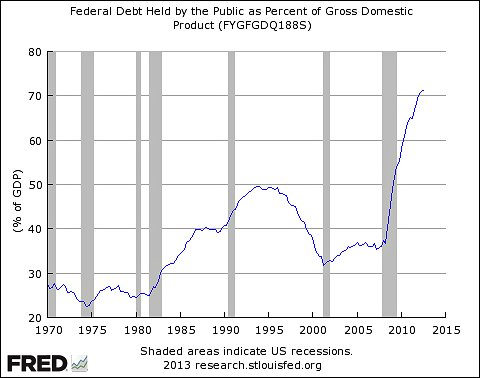

22 years, huh? Indeed, Boehner was elected in 1990, and entered the House at the beginning of 1991. So what kind of can-kicking was going on during his first, say, decade in office? Here’s the picture:

Hmm — it sort of looks as if the US was sharply reducing its debt during the presidency of a guy named, I don’t know, Bill something or other.

See what he did there? Boehner says something about spending; Krugman responds with an irrelevant chart depicting debt, and hopes you won’t notice he’s completely changed the subject.

And on he drones:

OK, joking aside, this is important. Republicans have invented a history in which it has been fiscal irresponsibility all along — and far too many centrists have bought into the premise. The reality is that we had low debt and no fiscal problem before Reagan; then an unprecedented surge in peacetime, non-depression deficits under Reagan/Bush; then a major improvement under Clinton; then a squandering of the Clinton surplus via tax cuts and unfunded wars of choice under Bush…

The problem here is that debt is not a measure of fiscal (ir)responsibility. If you buy a kayak you can’t afford, you’re equally irresponsible whether you take cash from your pocket, or make a withdrawal from your savings account, or put it on your credit card.

Fiscal irresponsibility is measured by ill-advised spending. And unfortunately, we can’t just pull up a graph showing the timepath of ill-advised spending, because we’re bound to have legitimate differences of opinion about which spending is ill-advised.

Krugman finesses that problem by a) talking about something other than spending and b) pretending this is relevant to Boehner’s remarks, which unambiguously are about spending. Presumably he’s learned over the years that his readers are too dumb to notice the bait-and-switch.

Conflating debt and deficit is just what a certain commenter here did to all my comments on the last spending thread, over and over and over. So Krugman at least seems to know his market.

Good post. Spending increased under Clinton and taxes increased even more. That’s how the deficit was reduced.

So is what’s irresponsible for a thousandaire to spend money on, the same thing that is irresponsible for a millionaire to spend money on? How can you say that it’s equally irresponsible to buy something ill-advised on your credit card as it is from cash? If we take the ill-advised spending as a sunk cost, would you be better off now having debt or having lost cash? (It depends on inflation and the interest rate you’re paying) I think his overall point is that spending in a depressed economy is not as fiscally irresponsible as spending in a booming economy, because real interest rates on 10 bonds are 0 or negative in a depressed economy and are positive in a booming economy. So to Krugman and his reader’s, taxing and spending are very much intertwined in what’s fiscally responsible.

My last sentence should have read, taxing, spending, and the real interest rate.

Daniel,

If we take the ill-advised spending as a sunk cost, would you be better off now having debt or having lost cash?

The effects are the same, i.e., your future spending capability remain exactly the same, regardless of whether or not you withdraw the money from savings or simply put it on a credit card. See The Armchair Economist, chapter 11 (I’m not sure if choosing chapter 11 was intentionally or coincidentally ironic) The Mythology of Deficits.

You may quite rightly believe that spending and debt are separate issues, but what Krugman knows and knows that his readers know, and you completely ignore, is that Boehner has been very very clear over the years that *debt* is the reason to cut spending. Spending is a problem, says Boehner, specifically because it causes *debt*. In other words, when we hear Boehner talking about spending, even when he doesn’t mention debt, we know enough about him to understand that’s the problem he’s been selling all along.

Your post is, I think, the bait and switch here, though it’s not clear whether you’re unaware of the context or believe the context doesn’t matter and that misinterpreting something by taking it out of context is more honest. If it’s the latter, then I think you’re mistaken and Krugman is right. If it’s the former, well, now you know :)

Steve, excellent point. And while we can’t pull up a graph of ill-advised spending we can pull up a graph of total spending. See attached – total government spending as a percentage of potential GDP (to take out the effects of business cycles). http://research.stlouisfed.org/fredgraph.png?g=fpc

The total spending graph would make a much better argument for Krugman’s narrative. Not sure why he would have chosen debt over this.

@cos: could Boehner mean debt is an extra reason to avoid foolish spending?

@Andy B

Quite the reverse. Some govt spending is core, but some is wasteful. The more the govt spends as a proportion the more will be wasteful. And destructive even, by skewing price signals. So govt spending as a fraction of GDP is positively correlated to waste.

@Ken,

I guess I think the fact that real interest rates are negative in a depressed economy implies that there are unused resources, which would imply that by spending now we could increase the ability to spend in the future regardless of whether the spending is “ill-advised”, whereas spending in an economy at full employment when interest rates are non-negative could reduce future spending if the spending is ill-advised. I’m defining ill-advised spending here as spending that would more productively be used in the private sector at full employment, in which case spending in a depressed economy would never be ill-advised.

I really liked the chart in Andy B’s link. With all the noise on the airwaves about cutting spending and raising taxes, the chart shows how focusing on robust growth would also have a huge impact on the economy. Yet we have policies that discourage labor force participation, a “jobs council” that didn’t meet for a year and has finally been disbanded, crushing regulatory enhancements, and more…

@Ken, also I’m having trouble understanding how an individual taking money from savings to blow money is the same as someone buying something on a credit card. If interest rates from a savings account are 3.0% on average and inflation is 2.5% on average, and credit card interest is 10% on average wouldn’t my future spending decrease more if I use a credit card because of the differential in interest rates?

The chart in Andy B’s link also highlights another game of obfuscation that Krugman has been playing lately. In several recent posts on government spending as a percentage of GDP, Krugman has argued that we should use NGDPPOT, which, evidently, is the “potential GDP” we’d have if the economy was running at normal employment. He argues in favor of doing this because the “share of GDP” plots are unfairly increased when GDP is below its potential.

Okay. Fair enough. And he has been somewhat consistent in doing this in his recent posts about government spending. But in his recent posts on corporate hoarding of profits, he has used plots that show corporate profits as a percentage of GDP, not of NGDPPOT.

The conscience of an obfuscator seems to be selective.

Professor,

Would you do a post on Cassey Mulligan’s work on unemployment?

@13: What a terrific catch TB.

BPC: I’d love to find time to read Casey Mulligan’s papers, but I’m not optimistic that I will, and I think it’s probably a bad idea to blog about stuff I haven’t read (though that doesn’t always stop me).

KenB wrote:

@13: What a terrific catch TB.

Seconded.

Another under-hand trick Krugman uses is to link the rises in debt with the President to score a political point. However, the US is not a dictatorship and the President does not decide the budget alone. If the debt is compared with Congressional control the Democrats come out worse, see:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:US_Public_Debt_Ceiling_1981-2010.png

@12: not the Ken you asked but beggars/choosers. For a large basically still sound country like the USA the “card” rate is the market rate, is what you would earn on the funds if you saved not spent them. Ken has pushed the analogy a bit too far. But you need to be understanding, he’s only a “Ken”, not a Ken with Initial, and allowances must be made.

Why do you assume it’s the economist, rather than the politician, who doesn’t know the difference between debt and spending?

I’m not sure I agree with the point here that the responsibility of spending is independent of income (or level of debt). Is it more or less responsible to spend $500 on a haircut when my annual income is $300,000 than it is to spend $500 on a haircut when my annual income is $500?

@13:

I don’t see that as a contradiction, I think there are valid reasons to use either potential GDP or actual GDP in different contexts.

When discussing the size of government, and in particular whether it has grown or shrunk, does it make sense to make that determination based on cyclically depressed GDP? Not so much.

On the other hand, when looking at the share of GDP that is corporate profits, why WOULDN’T you use actual, cyclically depressed GDP? Is there a reason to believe that profits will go down (as a percentage of GDP) when the economy recovers?

In other cases, like when discussing lack of consumer demand in the context of the current situation due to the declining GDP share of wage income, it may not even be relevant what corporate profits will be like in a recovered economy.

And I would like to underline the point made in post 6:

The reason why Krugman conflates debt and spending is because that reflects the political debate.

We’re supposed to have a spending problem which is evidenced by rising debt.

Arguably, if you can afford your spending, you don’t have a spending problem, right?

Does anyone here think we would be talking about a spending problem if US debt was going down?

Advo, point taken on the political realities but it’s nice when someone like landsburg steps in and shows how stupid the political debate can be. Certainly spending can still be unwise independent upon how you pay for it, ESPECIALLY when you are spending on someone else’s behalf…

KS:

I’m not sure I agree with the point here that the responsibility of spending is independent of income (or level of debt).

Nobody said that. Obviously a wealthier individual will (and should!) buy more toys, and a wealthier society will want more government-provided services. Equally obviously, this has nothing to do with the point of the post.

#22: “Is there a reason to believe that profits will go down (as a percentage of GDP) when the economy recovers?”

Isn’t this what Krugman is claiming will happen when he says this?

—

So, I’ve had a mild-mannered dispute with Joe Stiglitz over whether individual income inequality is retarding recovery right now; let me say, however, that I think there’s a very good case that the redistribution of income away from labor to corporate profits is very likely a big factor.

—

@22:

—

So, I’ve had a mild-mannered dispute with Joe Stiglitz over whether individual income inequality is retarding recovery right now; let me say, however, that I think there’s a very good case that the redistribution of income away from labor to corporate profits is very likely a big factor.

—–

I don’t see how that statement in any way claims that corporate profits as a percentage of GDP would be going down in a recovery; Krugman is claiming that inequality is retarding the recovery, he’s saying nothing about whether or it would ameliorate in a recovery, or am I misunderstanding something?

@21: Speaking as your barber, no difference.

@26: Yes you are missing something. The redistribution away from labor to profit. The wording clearly indicates PK is talking about changes here, cahnges that will reverse in a recovery when more labor is hired.

@28, The question is why would corporate profits expand as a percent of total income when the economy is depressed? That was more or less the point of the post. He was suggesting that maybe what was holding back recovery were companies hoarding profit. He was saying, that if those companies stop hoarding those profits as cash and start investing, we’d have a faster recovery. How would potential GDP even be relevant in this situation? It’s easy to see how potential GDP would be relevant for government spending targets, but how would it be relevant to the percentage of income companies are hoarding as cash?

Is a tax credit an example of spending or reducing taxation?

There are other problems with the chart. It shows debt as a percent of GDP rather than total debt and it only shows the portion held by the public (I assume that excludes on that debt held by the fed). Both could be important in some circumstances.

Anyway I do not think that the existing debt is a problem but that projected spending on Medicare and SS will need to be dealt with at some point.

simple question.

Why are corporate profits at a record high when the economy is still in such bad shape?

I would normally assume that record profits are far more likely during a good economy than a bad economy.

What am I missing?

Could someone pull Dr. Krugman aside and remind him, anent his chart, what happened in the 1994 Congressional elections?

I think the points and counter-points regarding GDP versus potential GDP are interesting, but I still don’t see a compelling case for using potential GDP for government spending, but then using actual GDP for private spending, investment and savings. Evidently, neither does Krugman.

As an example, look at his post today on “More About US Austerity”. As has become his custom, he uses potential GDP to demonstrate that total government spending is declining. Then he follows with a plot of private spending (on residential investment, I believe), and, again, he uses potential GDP to show a more dramatic decline. Here, evidently, Krugman believes that it is more appropriate to use potential GDP even for private spending and investment.

But when he made the case about private “hoarding” a few days ago, he used actual GDP which resulted in larger percentages because of the smaller denominator.

Krugman’s approach seems to be to use potential GDP to normalize the amount of money that is being spent, and to use actual GDP to normalize the amount of money that isn’t being spent.

So you’re right, but it seems weird to attack Krugman over this. Do you really think Boehner gets this distinction? Don’t you think he would make identical comments about the debt?

Right on the technicality, but I still don’t see how Krugman’s point is hurt at all on the substance.

I’m not saying Krugman shouldn’t have been more accurate – he absolutely should have. But I still walk away with the exact same impression of Boehner that Krugman intended, so I’m not sure where to go with this.

@33

This may be a valid criticism, but I still think that looking at government spending as a fraction of actual GDP is not a very useful or instructive tool in any case, whereas there are times when private spending as a percentage of actual GDP and as a percentage of potential GDP can be useful to know. As in for private spending as a percent of actual GDP, which spending categories, or stocks take on a larger fraction of GDP as GDP declines, and alternatively, for private spending as a percent of potential GDP, what fraction would they be taking if we were to ignore the effects of the business cycle. I think what Krugman was trying to point out in the post today, is that both investment in the public sector and in the private sector have declined relative to normal, while at the same time cash is continuing to pile up as a percent of total GDP, implying that savings and investment are out of whack which is a common theme on Krugman’s blog as of late. You could be right that Krugman was trying to exaggerate the increase in corporate holdings of cash to make a point, but I think there’s also the possibility that there was a more nuanced reason for this.

24 – sorry if a side point, but why does a wealthier society *need* more government-provided services, particularly as a % of GDP? Shouldn’t the ratio arguably go down?

Correct, of course, but a bit disingenuous. Boehner thinks the government spending is ill-advised *because* it is deficit financed. You can find lots of instances of him saying this, so Krugman is imply guilty of a logical ellipsis.

“sharply reducing its debt”? Debt in the Clinton presidency went from $4.188 trillion to $5.728 trillion. GDP grew at a faster rate, so the debt to GDP ratio went down. Good for us–but couldn’t he at least describe what happened accurately?

@36, There’s an argument to be made either way, but a more complicated economic system might require more overhead, just as a more complicated company requires more overhead. Think of it this way, how much regulation does a primarily agrarian economy require? Another argument is that higher per capita countries have already passed through demographic transition so their population has a higher average age and can afford to take care of their elderly. Just as an observation most modern economies take care of their elderly through government, hence another reason you might see the ratio increase.

Dr. Landsburg–

First, I agree, I’m going off on a tangent.

Second, correct me if I’m obfuscating you here, but my understanding is that you are basically saying that raising current taxes is analogous to frequenting the ATM more often (ie, increasing current tax revenue depletes future tax revenue) and NOT increasing your income (which would be analogous to economic growth)?

@iceman “24 – sorry if a side point, but why does a wealthier society *need* more government-provided services, particularly as a % of GDP? Shouldn’t the ratio arguably go down?”

Steve didn’t say “society will *need* more govt services” as it gets wealthier.

Nor did he say that society will or should spend a greater proportion of GDP on government services.

What he said was that a wealthier society will spend more on government services, just as a person earning $300000 a year will spend more on their car than a person earning $30000.

The wealth effect implies that a wealthy society will get either more or better government services, private sector services, recreation, food, healthcare, whatever (with a few exceptions, of course, where the wealth effect doesn’t counteract other factors). He’s not saying the wealthy society will spend a greater percentage of its resources on any particular one of these.

KS:

my understanding is that you are basically saying that raising current taxes is analogous to frequenting the ATM more often (ie, increasing current tax revenue depletes future tax revenue) and NOT increasing your income (which would be analogous to economic growth)?

Yes, exactly.

Daniel Kuehn:

Do you really think Boehner gets this distinction?

I think everybody above the age of eight gets this distinction.

Dr. Landsburg,

Well I think that would be a source of disagreement between you and a lot of the frequenters of this blog and myself. I don’t necessarily see a tradeoff between raising current taxes and depleting the future tax base. If the government can raise current taxes and spend it in a “productive” way, that could enhance future economic growth and increase future tax revenue as well. (Ie, say by building a public road between two town so trade is now possible).

Of course I guess this just comes back to what is a “productive” use of government spending and what is “ill-advised”, which is the point of your post.

– KS

It’s not just spending, but incurring off-the-books liabilities that should be budgeted (and therefore adding to debt) but aren’t. The entitlement trainwrecks of SS, Medicare, and now Obamacare don’t register in the debt/deficit numbers, but I’m sure were part of what Boehner had in mind.

@46: yes. It’s the spending that really matters. So your hypothetical spending would be good whether financed by taxes or borrowing. Just the fact of borrowing to fund it wouldn’t make it irresponsible.

43 – I know SL said “want” which is why I highlighted *need*. Unlike for an individual buying toys, the distinction seems meaningful when we’re talking about people spending other people’s money.

I also know SL didn’t specifically refer to % terms, but so much of the conversation about spending and taxes seems to revolve around things like a historical “target” % of GDP as a standard of reasonableness, and I question why it should be constant rather than declining.

Even in absolute terms, as Daniel 41 suggests demand for some things like “protective services” (e.g. from invasion, theft, fraud) should be expected to increase as we have more to protect. However, the need for social programs (which dominate the debate at this point?) arguably decreases. Here Daniel’s comment “most modern economies take care of their elderly through government” seems largely to involve a mere subjective preference over means.

@iceman: Here’s one way. Imagine society getting richer. Everyone has more wealth, so by diminsihing marginal returns cares less about the last small increase than people today do about a similar small amount. I miss $5 more than my richer future self misses $5. There might be government spending I am unwilling to spend $5 now that my future richer self is willing (or less unwilling) to pay for.

“so much of the conversation about spending and taxes seems to revolve around things like a historical “target” % of GDP as a standard of reasonableness, and I question why it should be constant rather than declining. “

Personally, I would suggest you question instead why it should be constant rather than declining or increasing. After all, there seems to be no simple way to link the statement “society gets wealthier” with any particular change in the percentage.

To form such an argument, you’d have to call on other factors.

Again to focus on one (pretty significant) aspect, would we agree as a society gets wealthier fewer people should require public assistance? Maybe not if we define “need” in a relative sense.

iceman,

Not necessarily. It depends how that increase in wealth is distributed doesn’t it? And again not if you think a majority of the elderly will need public assistance in the form of guaranteed medical insurance because of market failures. Don’t want to get in another argument about this again, but assuming the best way to take care of the elderly is through guaranteed medical coverage through the government, then you agree that as a nation ages a larger percentage of GDP will need to be allocated to government in this respect right?

53 – “It depends how that increase in wealth is distributed doesn’t it?”

No, presuming that no matter how an *increase* in wealth is distributed it can’t actually make anyone worse off in absolute terms.

I agree if you add aging demographics to the question AND you assume the best way to care for (all?) the elderly is through govt, you’ll probably draw the expected conclusion. But the increasing wealth part by itself makes that less clear (or clearly necessary).

iceman,

To your first point, I guess that’s fair, I’m just not sure if it won’t make anyone worse off. You might want to consider though that poorer countries don’t even have the ability to take care of their bottom distribution, so it might be that given that a country is wealthy, it prefers to help the bottom more, and this might be good for the country overall (assuming a very unequal distribution hurts economic growth).

In terms of aging, let’s just assume that at least 50% of the population will need help buying insurance in this case since that was the threshold before medicare was implemented and I’m assuming the cost as a percent of income regardless of the effects of government intervention has probably at least stayed the same. So as a population ages they’ll still need to allocate more resources (even if they only help those that need it) to the government to help the elderly.

@iceman “would we agree as a society gets wealthier fewer people should require public assistance?”

Personally, I find this too vague a statement to have a strong opinion.

Notably, as society has gotten wealthier, more people have obtained public assistance, and the public assistance has been better – think : government supplied roads, sewerage, water supply, education, incentives towards R&D, unemployment benefits, aged pension…. these are all far better now than they were 100 years ago.

So if you’re right that societal wealth tends to get people off government assistance, there must be some strong factors working the other way.

Perhaps, instead, “as more people obtain more and better government assistance, society becomes wealthier”?

If you narrowly define “government assitance” as “giving cash to people”, then this is doubtful. If you define government assistance as “providing valuable services the private sector is unwilling to provide”, then I suspect you can make a case that it’s almost tautological.

I was trying to focus on social support programs (a pretty big part of the discussion), all else equal

I don’t think anyone is quibbling about, say, clearly worthwhile infrastructure investment in the spending / debt debate

@iceman “I was trying to focus on social support programs (a pretty big part of the discussion)”

Ok, but this has also increase as societies became wealthier, no?

“I don’t think anyone is quibbling about, say, clearly worthwhile infrastructure investment in the spending / debt debate”

Except, of course, Congress circa 2012.