When I teach economics, I try to drive home the lesson that words are supposed to mean something coherent. If you want to be rewarded for stringing together a bunch of empty phrases, you should go take an English class.

I was therefore maximally sympathetic to the poor XM radio host (I think it was Pete Dominick but I’m not sure) who was stuck interviewing a man named John Sakowicz last Friday. Sakowicz, who hosts his own radio show in northern California, was there to warn about the dangers inherent in our growing national debt. He was very clear about this much: the debt and its associated dangers are massive, explosive, perhaps even apocalyptic. He was entire unclear, however, about exactly what those dangers are.

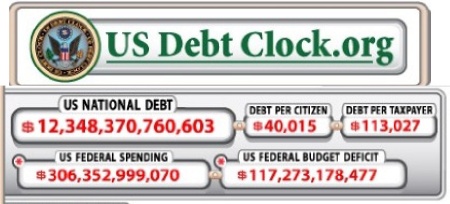

Pressed for an explanation, Mr. Sakowicz rather breathlessly announced that every child born in America today is born with a $45,000 share of the national debt. (He should have said the average child and $45,000 is probably not the right number, but those are minor quibbles). The host, bless him, asked exactly the right question, namely “What does that mean?”. To which Mr. Sakowicz attempted to clarify his meaning by repeating the $45,000 figure in a considerably more agitated tone of voice. To which the host calmly replied: “Okay, but what does that mean? Take my daughter, for example. Exactly how does this affect her life? Does it meant that she’ll pay that much more in taxes…..or what?”. To which Mr. Sakowicz replied that $45,000 is a really big pile of money.

Well, yes, $45,000 is a really big pile of money, but the host’s question was exactly on target. When we say that an American child is born owing $45,000, (or $40,000, or $350,000) what does that mean for the life of the child?

Answer: Pretty much nothing. What matters to your kids is not their share of the national debt, but their overall inheritance. There are two parts to that inheritance. First, there’s what your kids get directly from you. Second, there are the factories, machines and tools that other kids inherit, creating opportunities for your kids to earn higher wages.

What we collectively leave our kids is equal to what we collectively produce minus what we collectively use up. When the government commissions someone to build, say, a tank or a highway or a bridge to nowhere, using, say, a million dollars’ worth of resources, those resources are subtracted from the next generation’s inheritance—partly from your own kids’ and partly from other people’s kids’, which affects your kids’ wages. If you like, you can (perhaps partly) compensate for your kids’ share of that burden by tightening your belt and leaving a little more in your bequest. But the moral is that it’s government spending, not government debt that has the potential to impoverish our children.

To see that debt is not the culprit, suppose for a moment that we decide to eliminate the debt tomorrow by raising taxes, so the average American forks over $40,000. What does that do for the average child who’s born tomorrow? It removes a $40,000 debt burden and simultaneously cuts his inheritance by $40,000. How is that child’s life affected? To a good first approximation, not at all. (I am glossing over some complications here, but they are of relatively minor importance.) And of course that calculation makes perfect sense because the only way you can make the next generation richer is by conserving actual resources—which you can’t accomplish with accounting tricks.

Ah! you might say, but we’ve done more than that—we’ve saved that child not just from $40,000 in debt but also from a lifetime of accumulated interest on that debt. Yes, and we’ve also robbed that child of not just $40,000 in inheritance but also of a lifetime of accumulated interest on that inheritance. It all washes out.

This is why it’s so frustrating to hear talk of blue ribbon commissions assigned to the task of “debt reduction”. “Debt reduction” can mean less spending, or more taxes, or some combination thereof. But to raise taxes solely for the purpose of debt reduction is to mask the problem, not to solve it. Debt is not the problem; spending is. Hysteria about the debt is misdirection.

Edited to add: In the month of January, the federal government spent approximately $1000 per American.

Of course, “no estate taxes” is part of that good first approximation, right? When one’s ability to pay his kids’ share of new government spending is diminished, government debt really does become a separate problem that is better solved now rather than through your ideal-world inheritance.

Debt can be repudiated, and at some point will have to be, explicitly or otherwise. Spending, however, comes with constituencies that lobby for its continuation. Thus it may well be the case that the only way to stop spending is to increase the debt until it is repudiated. Then no one will buy future debt. Then spending will be associated with tax increases, and constituencies that want more spending will have to battle constituencies that want less taxes. In this context, increasing the debt can actually be a long-term strategy for less government.

I really enjoy these post about debt, deficits and the likes, because they often dispel some popular notions about how economy works. But there is one thing I don’t understand. You make it sound as if the size of debt accounts for absolutely nothing as far as the lifes of future generations are concerned. Is it really totally irrelevant if the debt dissapears or doubles overnight?

It is best to start by making clear that I am in complete agreement that wasteful, or even harmful, government spending is the main problem. However, the amount of debt per person is also potentially dangerous, because of the uncertainty associated with it.

As I learned from The Armchair Economist, I can very well buy government bonds to cover the cost of higher taxes in the future (due to debt repayment). However, I do not know exactly how much taxes I’ll have to pay, and when: maybe the tax hike will happen after my death, in which case I don’t have to worry unless [a] I have children and [b] I can leave to them the bonds without death duties (as Ben points out) and [c] I think it likely that my children will not emigrate. Otoh the debt repayment might happen sooner than I expect, and might be more burdensome than I expect; but it can also happen that the government cancels its debt (as RL expects), either explicitly or through higher inflation. I could buy some sort of insurance to cover all these risks; but if the government can go bankrupt, so can the insurance company.

Added to all of this is the problem that governments are more likely to increase spending when they do not have to raise taxes at the same time. And in addition, the higher the government debt relative to GDP, the more likely is default or high inflation, and therefore the higher the interest that the government will have to pay on debt. Italian governments (all of them) were severely burdened by interest on debt, before the euro was introduced and reduced the risk of inflating away the debt (if not the risk of outright default).

I wonder whether these are the complications that our host says he glossed over; they might be “of relatively minor importance”, but not of negligible importance.

Snorri: All of your points are good ones.

OK, so let’s say one is persuaded that the government default or hyperinflation is a realistic scenario, and ruling out insurance since the insurance company may default also, what is the appropriate investment strategy?

While reading this my brain reminded me of another article by Steven Landsburg titled Don’t Pay Down the National Debt: It’s a great deal

The basic idea being that the U.S. government can borrow less expensively on our behalf because they can force us to pay.

Dick, one possible investment would be TIPS, which are bonds protected against inflation.

Dick: another possible investment would be a basket of foreign bonds or currencies (assuming that you think that they won’t default), or a commodity (like gold). You could even short the US interest rate futures while going long on foreign ones if that was really a concern.

Josh, I don’t get it, who is this Steven Landsburg guy?

;)

Landsburg,

Seems like your comments are based on a fallacy of relevance. There is an implicit assumption that future generations will not benefit from our actions. While those actions can be based on debt, it does not follow that all those actions make the future generations worse. How would future generations value, for example, a road built as a result of debt obligations? What if those future generations use the road? What if they need the road to get to work? And on and on it goes..

Of course, I do not expect you to take the idea serious. Your motto is summed up quite literally in the expression: “Blame government all the time for all things, ad naseum.”

(Enjoyed your price theory book a few years ago. As I’ve matured and taken more advanced courses in finance though, I must say, your simplified assumptions are remarkably ridiculous.)

Joe: Absolutely, government does things of value. Those things have benefits and they have costs. Sometimes the benefits are worth the costs and sometimes they’re not. The point of the post is that the costs are properly measured by spending, not by debt.

Good economics lesson but it could be misleading politically. It is quite correct to focus on spending rather than “debt.” It is not correct to ignore deficits because to some extent, they represent spending decisions gone awry. Take the GWB drug benefit. Would it have been passed if the Republican party had not been willing to overlook it’s contribution to future deficits? It seems to me that if Republicans really wanted smaller less intrusive government, they would be trying to tie every spending increase to a tax increase (the PAYGO rule they uniformly opposed in the Senate) , counting on the unpopularity of taxes to control spending.

Another subtler problem is that this basic analysis is based on full employment of resources. This is a good basis for analysis over the long term and a good framework for thinking about the public spending decisions most of the time. Ten percent unemployment is not one of those times. The spending on preventing the policeman or librarian from being laid off cost the future nothing, regardless of it having led to iahigher defitit and an accumulation of debt.

Debt growing faster than the economy plus a distortionary tax system can impose a higher cost on the economy (a higher excess burden of taxation), but I doubt that Sakowicz had that in mind.

Expanding on what Joe said above, I believe that this statement in the article is too simplistic:

“But the moral is that it’s government spending, not government debt that has the potential to impoverish our children.”

I don’t necessarily have to be a complete tightwad to not impoverish my children. I can spend money in a way that leaves them with assets – that doesn’t WASTE my money. Of course, I could also go to vegas and waste away their inheritance. So it’s not just my spending that affects them – but rather whether or not I have spent WISELY.

In your tank example above, we’ve left the next generation a useful asset for defense. Even if it gets used up, we presumably have left them an intangible asset in terms of security – unless we used it unwisely. The same with govt spending in general. Was it frittered away in a manner that left our heirs no lasting benefit or did we leave them a better country – with either more tangible assets like roads and bridges or even intangible benefits. Just be careful what counts as an intangible. For example, has all our spending on poverty done anything to reduce poverty in this country?

“Debt is not the problem, spending is.”

Isn’t the problem one of government spending that doesn’t have the net effect of increasing the value of our children’s inheritence rather than government spending per se? For example, spending that provides public goods or addresses common-pool resources come to mind, and if we expand our concept of values that contribute to our children’s inheritence beyond strictly economic ones, say social cohesion or equality of opportunity.

Steve, I must respectfully disagree with your argument that the debt that we leave our children will be roughly equal to the inheritance that we leave them. I agree that spending is the true culprit in this equation, but I would argue that spending and debt cannot be separated from one another from an accounting standpoint. In your equation, debt incurred is offset by inheritance (or assets) left behind. This would be true if all of the debt that our government was incurring was spent on infrastructure and other hard assets. Unfortunately this is not the case. Much of the debt that is incurred is used on spending that would be classified as expenses in accounting. These include many of the subsidies that are paid to welfare recipients, farmers, research, government salaries, etc. I am not claiming that any or all of these are inherently bad, but they are not hard assets (or inheritance) that our left behind for our children.

To put it simply, I think your argument that reducing spending should be our main focus is accurate, but the level of debt that is incurred to support that spending is equally important because in a society with ever increasing entitlements (i.e. expenses), an ever decreasing portion of the debt that is left behind is offset by assets (inheritance) to be used in the future.

Here’s what I’ve always wondered about this:

When the government increases debt by a trillion dollars, suppose that means that the owners of a given house (assuming they are subject to U.S. taxes, which is likely) will expect to have to pay $5,000 of that (with interest) at some point in the future. That should lower people’s willingness to live in that house, or any house in the U.S., as compared to, say, becoming a Canadian. So it should lower the value of the house by about $5,000. Values of houses all across the U.S. should be lowered by similar amounts, and the total amount that the values go down by, should add up to whatever portion of the debt has to be repaid in the future by U.S. homeowners.

Or, consider the portion of the debt that will have to be repaid by U.S. corporations that will still be in existence when the debt comes due. Then that should lower the total value of all of the corporations by the total portion of the debt that they’ll have to pay.

In other words, responsibility for repayment of the debt will fall to the owners of certain entities, and if those entities exist *now*, then the value of those entities should fall accordingly, so that the future debt actually comes due immediately, in the present, in the form of decreased valuation of those entities.

Why doesn’t that happen?

He was entire unclear…

I’m NOT an English major ( :-) ) and would be filthy rich if I had a penny for every typo on my blog, but I think this should read:

“He was entirely unclear…”

PS. Would it be OK to add your blog to the “Blogtopus” links at Sonicfrog? I always ask; it seems like good blog etiquette.

I notice nobody wanted to talk about the Debt per Taxpayer number. $113,000 per head … the debt service on that alone is north of $4,000 per year and will probably rise dramatically. That is part of spending and it creates nothing, no roads no bridges, nothing.

Based on a population of 300 million the 2011 budget projects about $13,000 of deficit spending per taxpayer in 2011 alone.

So much for me retiring in 10 years … :)

Bennet,

It’s because of something Mr. Landsberg and other economists often gloss over, because it’s so obvious to them it doesn’t seem worth mentioning: One person’s debt is the next one’s asset.

It’s complex and often counterintuitive, because it leads to “turtles all the way down” concepts.

Regards,

Ric

Debt is fine but when you have a Ponzi scheme — which is exactly what we have — it’s a major problem. We have debt that could never be repaid even if we tried. We have unfunded liabilities that can never be paid. Period. It is just a matter of time before the you-know-what hits the fan.

We are becoming a country of trickle-up poverty. The notion that “it all washes out” is nonsense. Tell that to the states with huge debts and fleeing taxpayers. How do you tell our children that the $113,000 dollars of debt that they have been saddled with is compensated by the fact that they are in a country that is losing jobs and will never be able to give them the retirement benefits (i.e. Medicare, Medicaid, Social Security) that they are currently paying for and is the current reason for that debt?

We’ve got a president and Congress spending money like a crack whore with a stolen credit card. 8,000 pork projects, military aircraft flights for children and grandchildren and on and on. Remind me again how that washes out with the bill that the rest of us are left with.

The discourse about the “wash” misses the fork between the interest paid on debt and the interest accumulated on iheritance. If you take $100000 in debt, you have to pay more in interest over a period of time than you would receive in interest off $100000 in a bank. It is far from a “wash”.

What is the economic effect of war on children ?

Wealth can be lost, or destroyed, more easily

than it can be created, and Our Feckless Leaders,

in economic extremis, are just foolish enough

to get the US into a shooting war with the Chinese,

and lose a Carrier Battle Group, or perhaps the

Hawaiian Islands, as a result.

Note: This is not my paranoid nightmare:

The Chinese, who never say anything without forethought,

are on record as saying that the US will not try to rescue

Taiwan at the risk of losing Los Angeles; They are not bluffing.

Debt, particularly foreign debt, does matter.

It doesn’t happen because the government can also treat dollars as a commodity so that the dollar value of your house continues to go up, even as the real value goes down. Its quite the trick.

Bennett Haselton-

This effect does occur, say with property values. Local property taxes, commute times to employment centers, sewer charges, microclimates with different heating/cooling costs, etc. all have an impact. Whenever the buyer has this information, the price is impacted.

Since government debt isn’t connected directly to government revenue collection, this information isn’t available to the “buyer”. This is asymmetrical information at its “finest”, and this is the “uncertainty” that people talk about.

Bennett,

When a corporation increases its debt, all else equal, their stock price does go down. For this to work in the public sphere, wouldn’t there have to be people buying and selling “ownership” in the US (and more strongly, that everyone be doing this, or at least have that option, including future unborn generations)? I don’t see the mechanism

I’m trying to be persuaded, but here is why I am not.

Debt is the tangible manifestation (I took an English course) of the Governments inability to control spending. Therefore, it matters a great deal.

If I’m reading correctly, in a text book debt by itself would not matter. Or matter as much.

In the real world, telling a politician that debt is not what matters is like offering an open bar to a room full of alcoholics.

A very bad idea indeed.

Of course debt matters. Because sooner or later that debt will be settled. When the debt is owed to foreign nations, like China for instance, the only way to settle that debt is to pawn off parts of the country, the way Russia pawned off Alaska to the States to pay off debt. Eventually, our children will inherit less because it was sold to pay debt.

“What we collectively leave our kids is equal to what we collectively produce minus what we collectively use up.”

Not exactly. What we collectively leave our children is the sum of what have inherited from our fore bearers, plus what we produce ourselves, minus what we consume ourselves. Most of what we leave behind is comprised of what we inherited. Each generation does not reinvent the wheel or build whole cities. Each generation simply adds value to what is passed along. Or is supposed to.

However, since what we consume is purchased mostly by taking on debt, we therefore leave the next generation with that much less.

Spending wealth is not the issue ultimately then, if it is wealth that we have earned ourselves. But the wealth we spend is not earned ourselves. We are producing very little wealth now. We are consuming more wealth than we are producing, so we are not adding any value to the America we leave behind. We are producing a net loss.

America has gone from a country that produced and exported, to a country of shoppers and money traders. Someone who works in a store selling foreign goods to American shoppers does not produce wealth, just as someone who works in government produces no wealth. Their jobs might be vital, but they produce no wealth. None of those activities produces wealth. Factories have been replaced by Wal-Marts. Now it is the Chinese that produce the wealth. And since our economy is 65% consumer spending, the only way we continue to have employment is if we continue to go into debt, transferring wealth from what we inherited from our American parents, to the Chinese.

Dear Mr. Landsburg:

I’m the guy you reference above, and I have to say you sound like a fool. Where is it exactly that you teach economics?

Let’s look at the cold, hard numbers.

Last week, the U.S. Senate voted to increase the national debt by a whooping $1.9 trillion to $14.3 trillion. The Democrat-controlled House of Representatives will soon follow.

Do the math. Divide that number by 305 million Americans.

Now take the number at which respected folks on Wall Street are projecting at which the GNP will grow. I use Bill Gross of PIMCO’ number. Bill Gross is the top money manager in the world. He is also the smartest guy on Wall Street, in my opinion (with all deference to you, Mr. Landsburg).

Bill Gross is projecting economic recovery to be weak going into the foreseeable future. He projects a paltry 2.0 %.

Do the math again.

With a debt load that grows by an annualized double digits, compounded by debt service, where is the money going to come from to pay the national debt?

Add to that sad scenario that the debt service is currently artifically low because the Fed is keeping rates artifically low at 0.0 to 0.25 %, once other members of the G-20 rates rates, the Fed will have to do the same to stay competitive in pricing our Treasuries auctions, which are monstrous in size, I may add.

Incidentally, China is already indicating it will raise rates by June. And China will soon overtake the U.S. as the world’s financial leader.

Put that all together, Mr. Landsburg. Conclusion? The U.S. can’t grow its way out of debt.

And that was my main point, Mr. Landsburg. The only way the U.S. can repay its debt is with devalues dollars that are worth less than the dollars we are currently borrowing.

Inflation will get us there. Hyperinflation

And that is the leagacy we are leaving our children, Mr. Landsburg. I’m glad you are comfortable with this. But I’m not.

Final footnote. Our founding fathers knew that the way to subjugate our nation’s people was not just through marshall law or a police state or a dictatorship.

Instead, they knew that a very real way to subjugate the people was the control the currency.

And the best way to rob the wealth of the people was to devalue the currency through inflation. It’s a slow and insidious process, but it’s as effective as being robbed at the point of a bayonet.

Steve (Landsburg):

Absolutely, government does things of value.

No doubt that is true. And yet, I cannot help liking the idea that every governmental action achieves the opposite of what was intended: it appeals to my contrarian side. (I have seen this quoted as Howard’s Law, but I have no idea which Howard formulated it.)

I also like John Locke’s idea: “government has no other end but the preservation of property.” Perhaps Howard’s Law only applies when government steps out of this boundary.

Bennet, the reason the values of companies do not always go down when they incur debt is because in the private sector, unlike government, it is not a zero sum game. when a company borrows money it is usually doing so in order to make investments and to pay obligations that will allow it to provide products and services for which it will earn a profit. The obligation to repay the debt is in the future and though there will be interest and other possible opportunity costs with borrowing the money, the gamble is that those future profits will more than offset those costs.

You are correct that in the area of government debt does reduce the overall value because government does not produce anything. When it borrows money it is typically so that it can pay other people to produce things and to get things done like roads and bridges, etc. On top of that, the government does not have any incentive to make a profit when it buys these services and resells them to the people in exchange for taxes. In addition, because there are a number of government officials that administer this whole process without producing anything themselves, there is additional cost that prevents the government from breaking even on these transactions which makes the government scenario worse than a zero sum. Unfortunately, for many things this is a necessary evil, such as defense, some infrastructure and law enforcement. For most other things however, private companies that generate profits to offset the cost of their borrowings is a much better option.

Author,

It is true that if you were to go to the bank and get a loan, you’d pay more in interest then you’d get in interest with a savings account.

The federal government’s debt is, for some reason, still considered default risk free and therefor, pays the lowest interest rate possible. If you are the average American with plenty of credit card debt, you’d be much better off with the government as your cosigner; raising its deficit rather than you paying more taxes and raising your higher interest credit card debt.

Mark said, “Someone who works in a store selling foreign goods to American shoppers does not produce wealth, just as someone who works in government produces no wealth. Their jobs might be vital, but they produce no wealth.”

Someone (whether foreign or not) who works in a store selling foreign (or domestic) goods provides wealth to the owner (whether foreign or not) of the store because presumably the owner of the store is now free to do other (more profitable) activities.

Interest payments on national debt represent around 10% of government spending and the fourth largest single expenditure

(http://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/budget/fy2009/pdf/budget/tables.pdf)

The actual cost of paying the debt at some future time is not the problem, the problem is in ongoing maintenance costs for such a large debt. As more of the debt is held by foreigners, this is just a black hole that money needs to be thrown into every year.

Dear Mr. Landsburg,

Please allow me to update my post.

Obama just released his FY 2011 budget today…a whopping $3.8 trillion.

Futhermore, Obama forecasted a defict of $1.6 trillion this year, which, of course, follows last year’s deficit of $1.4 trillion.

And Obama said that the 2011 deficit would be $1.3 trillion, with deficts easily staying above $700 to $800 billion for the rest of the decade until the year 2020.

To put this in perspective, Mr. Landsburg, the 2011 deficit of $1.6 trillion deficit in 2011 represents 10.6 % of Gross Domestic Product.

This 10.6 % is the highest percentage of GDP since World War II. In fact, the 2011 deficit as a percent of GDP is twice the average since World War II ended.

I say again, sir: If growth is projected at 2.2 to 2.5 % by the consensus on Wall Street, and by only 2 % by Wall Stret’s best and brighest money manager, Bill Gross, how will the U.S. pay down its national debt?

It won’t come through growth.

The only we can pay down that debt, or more realistically just roll over that debt, is with devalued dollars.

Devalued dollars.

And that’s when our children and grandchildren will be living not in the America that we had the good fortune to grow up in, but in an America that will be just another debtor nation among debtor nations.

Ten or twenty years from now, America will be in the unhappy company of most of the Third World — owing onerous amounts of unpayable debt, and while at the same time we’ll be saddled with high inflation and high unemployment, and little or no growth, and quite possibly negative growth, and a contraction of GDP in real, inflation-adjusted terms.

Sounds like Botswana, doesn’t it?

It strikes me funny how the party that is out of power, R or D, always obsesses about the national debt more than the party that is in power.

John,

But isn’t your broader point that we are spending money where it shouldn’t be spent? I just don’t understand why in your latest post you don’t mention which projects/programs we should eliminate. Landsburg’s point I do believe is that once we’ve decided to have certain programs, we have two choices: increase taxes now to pay for them or increase taxes later. But the whole root of the problem is the spending to begin with and whether it’s a good thing to spend our money on any given project/program.

Author said “The discourse about the “wash” misses the fork between the interest paid on debt and the interest accumulated on iheritance. If you take $100000 in debt, you have to pay more in interest over a period of time than you would receive in interest off $100000 in a bank. It is far from a “wash”.”

The scenario you present above is not a wash in an accounting sense, but in a true economic sense you pay interest for the right to use someone else’s money as you please, for a certain period of time. I’m not sure who borrows money and just lets it sit around in a low-yield savings account. Hopefully, when someone is borrowing money they are using the money in a manner that yields to them something greater than the interest rate they are paying on the debt.

John,

You keep acting as though the only way to pay off the debt is by devaluing the dollar. What about raising taxes? You haven’t remotely answered Prof. Landsburg’s argument, all you have done is quote random figures and create doomsday scenarios. And while you are interested in quoting some figures, the treasury yields as of today range from 0.10% for 1 month and 4.56% for 30 years. So why are you so afraid of inflation when the market is not?

“To see that debt is not the culprit, suppose for a moment that we decide to eliminate the debt tomorrow by raising taxes, so the average American forks over $40,000. What does that do for the average child who’s born tomorrow? It removes a $40,000 debt burden and simultaneously cuts his inheritance by $40,000. ”

Does this require the Ricardian equivalence to be true (empirically, it is not)?

Suppose the government wants to spend on something and must decide between raising taxes by $1 or borrowing $1. It seems like you are claiming that if the government borrows $1, the children will have a $1 larger inheritance, and so they won’t care. But what if the parents just consume more and don’t leave their children more inheritance? Then doesn’t the debt cause an intergenerational transfer from the children to the parents?

Anonymous: If the parents choose to consume more in the presence of debt, they are presumably grateful for that opportunity. Those parents (including, presumably, Mr. Sakowicz) who are very concerned about their children will behave otherwise—leaving them nothing to complain about. So who is left to be offended by debt?

What about the children of the less caring parents? It seems like the debt is making them pay for their parents’ pleasure without their consent.

Anonymous: What about the children of the less caring parents? It seems like the debt is making them pay for their parents’ pleasure without their consent.What about the children of the less caring parents? It seems like the debt is making them pay for their parents’ pleasure without their consent.

Could be. But I don’t expect those parents to be complaining about the debt. So it’s hard to see exactly who *could* complain about it consistently.

My point is that it is the children of the less caring parents who could complain about the debt consistently, because their money is being taken from them.

The flaws in Ricardian equivalence (the economic jargon for this principle) should not detract from the fact that it is at least a reasonable approximation. Steve Landsburg’s example may not be rock solid, but it certainly beats John Sakowicz’s hysteria.

Additionally, it’s not unreasonable to leave future generations with debt given that they’d likely be richer (see another Landsburg article). Since future generations inherit the non-scarce technological advances of previous ones, principles of vertical equity would suggest that we consume more scarce resources today to compensate.

Ah! you might say, but we’ve done more than that—we’ve saved that child not just from $40,000 in debt but also from a lifetime of accumulated interest on that debt. Yes, and we’ve also robbed that child of not just $40,000 in inheritance but also of a lifetime of accumulated interest on that inheritance. It all washes out.

Oh … but the deadweight cost of taxes, which rises by the square of the rise in the tax rate — as needed to finance increasing debt — does not wash out.

Nor is this any minor, second order effect on the course we are charting.

CBO has projected that just to stay even with just the rising operating costs of Social Security, Medicare and Medicaid, income tax rates will have to rise by 50% by 2030. That implies a doubling of the deadweight cost of taxes from current levels as a pure drag on the economy. (And this projection was made before the current recession and the far worse projections that have resulted from it).

Ah, but that’s the happy scenario, with these expenses actually being paid by current tax increases. Debt financing the same expenditures produces a result that is much worse.

The same study says that if these expenses are instead debt-financed GDP growth will first slow under the burden — and then collapse straight down. (Figures 3 & 4)

That’s because as debt piles up the interest on it not only grows but compounds, thus tax rates go up faster, accelerating — and the deadweight cost of taxes becomes crushing. Today income taxes are about 10% of GDP. Make them 15% (2030) DWC doubles … Make them 20% of GDP and DWC quadruples .. Make them 25% of GDP and DWC goes up over 6-fold…

That’s what debt does. Moodys, Fitch and S&P all project the credit rating of the US will start falling in the next few years if the deficit/debt situation is not addressed. S&P has projected it will fall to “junk” by 2027. (And that was a pre-recession projection too.)

Certainly whether the government spends productively or wastefully has a big impact on future national welfare.

So does the amount of debt it runs up doing so — and the tax rates that result out of necessity to finance it.

As I learned from The Armchair Economist, I can very well buy government bonds to cover the cost of higher taxes in the future (due to debt repayment).

I hope this isn’t the old: “I can avoid the cost of the national debt (or other taxes) by buying enough of the debt to receive the cost back in interest payments *from* the government” fallacy!

Illustration: The govt spends money on something and debt-finances it, adding the cost to the national debt. Say that “my share” of the debt increase is $100k and the interest rate is 5%, so “my share” of the income taxes used to pay it = $5,000. I incur a new $5,000 income tax cost.

I am out of pocket by $5,000 cash every year — my annual consumption/savings must decline by that much, reducing my welfare accordingly.

But, of course, I could get that $5,000 cash right back from the govt by buying $100,000 of its bonds. That makes the tax cost/inerest income cash flow a wash. Have I eliminated the tax cost landing on me? Not at all, not by a cent.

To buy the $100,000 of govt bonds I have to get $100,000 cash from somewhere — either from reducing my consumption, or by liquidating investments — reducing my welfare accordingly.

How much is my welfare reduced? Well, $100,000 at a 5% interest rate equals a discounted to present value cash flow of $5,000 per year.

So to get the $100,000 to buy the bonds costs me the equivalent of $5,000 per year — the exact amount of the tax.

Scenario 1: I just pay the $5,000 tax annually. Net -$5,000 annually.

Scenario 2: I pay $5,000 tax annually, buy the $100,000 of bonds to get $5,000 of income annually, pay the equivalent of $5,000 annually to buy the bonds … -$5,000 + $5,000 – $5,000 = net – $5,000 annually.

(And this cost doesn’t even consider the deadweight cost of taxes.)

If one could “very well buy government bonds to cover the cost of higher taxes”, then one could buy yet more government bonds to more than cover the cost of taxes — and profit outright!

If only!!

Jim Glass:

To buy the $100,000 of govt bonds I have to get $100,000 cash from somewhere — either from reducing my consumption, or by liquidating investments — reducing my welfare accordingly.

Yes, and buying that $100,000 bond is exactly as painful as paying a $100,000 tax, which is what you’d be paying under a pay-as-you-go plan.

Nobody claimed that buying bonds could relieve you of the burden of government *spending*; the claim is that it can relieve you of any excess burden of government *debt*.

Jim Glass: If the government spends an amount of money and confiscates assets by taxes in order to fund it, and your share of the confiscation is $100k, then you manage to avoid the $5k yearly burden to service the debt. But you are also out $100k of assets, regardless. If you do not have such assets, but are still responsible for the $100k taxes, you might get to enjoy some time in a prison somewhere.

If the government debt-finances the spending, you must sacrifice the $100k assets buying government debt (or, if you are willing to take more risks, some other higher-yield assets). But the government debt you hold earns interest in an equal proportion to the yearly burden in order to service the debt.

In either situation, the number to be concerned with is the amount of government spending. Not the manner in which the government pays for its expenses.

Ah.. I see Dr Landsburg beat me to it. Oh well. A lost opportunity for me to appear smart.

Nobody claimed that buying bonds could relieve you of the burden of government *spending*; the claim is that it can relieve you of any excess burden of government *debt*.

1) Please define the “excess burden of government debt” that allegedly is being relieved.

In the numerical example above the dollar cost is identical both ways, so where is the “relief”?

Checking the original Slate piece where I first read this idea (btw, I still remember it because I am a fan of yours, but this one always irked me) the claim was that by buying enough bonds to get back in interest what one pays in taxes to service the debt…

“For all practical purposes, you’ll have opted out of the debt burden entirely”.

That certainly reads like one is getting out of something, some “burden”.

Yet the “debt burden” is the tax cost of servicing the debt — what else? — and using this tactic leaves that tax cost, the transfer to the gov’t, exactly unchanged, both in amount and timing. So exactly what has one “opted out of”?

If nothing at all has changed, apparently nothing.

It would seem to be much more clear to say: “There is no excess burden of government debt, over the cost of the taxes needed to cover government spending.”

Yet that is something very different. In that case there is nothing to opt out of, and the whole exercise of buying bonds is pointless.

2) A major economic cost of piling up debt is still being ignored. See below.

Jim Glass… In either situation, the number to be concerned with is the amount of government spending. Not the manner in which the government pays for its expenses.

Saevar: Say this: “the deadweight cost of taxes on the economy increases with the square of the increase in the tax rate“.

For instance:

Say that in each of periods 1, 2 and 3 the gov’t spends $X, or $3X total, which could be covered with a steady tax rate of Z%. But instead, in its wisdom, the gov’t decides to entirely deficit spend during periods 1 and 2, and to defer all the tax cost into period 3, in which it collects tax of $3X.

You may say: “It doesn’t matter. The gov’t still collected the exact same $3X in taxes. By not collecting $X in each of the first two periods it just left that much more available to be collected in the third period. It’s a wash.”

But it is *not* a wash! Because in period 3 the tax rate needed to collect all the tax is 3xZ% , triple the steady tax rate that would have done the job. Thus, in period 3, the deadweight cost of taxes is nine times (9X !) what it would have been otherwise.

Let’s define the deadweight cost of taxes as 1 unit per time period for the tax rate of X%, if applied steadily over all three periods. Then tripling the tax rate in period 3, increasing the deadweight cost nine-fold in that period, to nine units, which also triples the deadweight loss to the economy over the entire three-period stretch.

That’s no wash!

Now, if you think the current deadweight cost of taxes to the economy is trivial, then you can ignore all this. But if you think it is significant already, this is something to seriously be concerned about.

Feldstein puts the current deadweight cost to the economy of income taxes at $0.76 per dollar of tax collected at the margin. Boskin puts it closer to $1.40. So, if they are right, we are talking about an already serious cost — which large-scale deficit financing will multiply geometrically.

I refer you again to CBO’s projection of, and explanation of, our economic future if it is deficit financed. (charts 3 & 4). And S&P’s picture of the US credit rating in 2027 if projected spending increases are financed with debt.

Reinhart & Rogoff’s new book documents 40-odd countries that have defaulted on their national debt since 1970, at great cost to themselves, due to excess debt. In many cases on domestically owed debt, not debt owed to foreign creditors. If the amount of debt a nation incurs really doesn’t matter, that is a very bizarre fact.

Jim Glass: Deadweight losses are not trivial. They represent opportunities to make everyone better off. Or at least, some of us better off without making anyone else worse off. What they do not represent, as far as I know, is confiscation or reallocation of assets.

Your example is a bit off. The paper you linked says, as best that I can determine, that deadweight losses quadruple as taxes double, all else being equal. But all is not equal. In your example, the deadweight losses in period 3 are, at a 3Z tax rate, nine times the deadweight losses of period 3 at a Z tax rate. No more, no less. The paper doesn’t say anything about the effects on period 3 from no taxation in periods 1 and 2.

Lets say the government taxes yearly. You earn $60k/year and the government taxes you $10k/year. You keep $50k/year and live a life.

Now say the government is going to take taxes every 3 years. You not only earn $60k/year, but because you get to keep all your wages, you work a few extra hours a week and actually take home $65k/year (leisure time being relatively more expensive, and thus you consume less of it). You know your tax bill is going to come due down the road and buy up $10k of government debt a year. Year 3, you earn your $60k (you don’t work more hours, preferring to avoid accumulating tax burden) and the government taxes you $30k to pay for its projects. You cash your $20k of bonds and end up in year three with $50k of income.

This is not precise, of course, because I haven’t accounted for interest on either side. Interest on the debt will raise the amount the government taxes you. But it will also raise the amount you receive when cashing your debt. The deadweight loss in year 3 will stem largely from the fact that you -could- have consumed immediately or invested in more risky ventures (with consequently higher returns) but did not in order to cover your future tax burden.

Jim Glass: … Your example is a bit off…

As a rather extreme illustration posted at 3AM, how could it not be? :-) But not too much so.

Look, in your argument …

“the number to be concerned with is the amount of government spending. Not the manner in which the government pays for its expenses”

… you are really saying two different things:

1) In dollar amounts (at present value) spending always equals taxes — whether the taxes are collected up front to pay for the spending right away, or on a deferred basis to carry the national debt.

This is entirely true. The tax cost of an expenditure paid up front equals the present value of tax-financed interest on a perpetual bond used to debt-finance the same expense. So there is no “extra” dollar cost of debt financing, via interest or whatever. (As Milton Friedman used to say, spending determines taxes.)

*and*

2) Because that dollar cost to be paid is always the same, “the manner in which the government pays for its expenses” makes no economic difference.

This is false, because of the deadweight loss cost of taxes. Different taxes have different deadweight cost, so that matters. And timing matters, because e.g. if taxes are deferred to “pile up”, their deadweight cost rises with the square of the increase in the tax rate. So a 10% rate increase ups DWL by 21%, etc. And that’s very un-economical!

The paper doesn’t say anything about the effects on period 3 from no taxation in periods 1 and 2….

It’s simple: DWL increases by the square of the increase in the tax rate. There are plenty of ready references (e.g. Mankiw “if we double the size of a tax, the deadweight loss increases four-fold; if we triple the size of the tax, the deadweight loss increases nine-fold. The graph of the deadweight loss as a function of the tax takes the shape of a parabola.”)

Any serious tax discussion has to consider deadweight loss. If not for it, we could have tax rates of 100% with no economic loss at all! So DWL *is* the cost of taxes.

Lets say the government taxes yearly. You earn $60k/year….

Let me re-stylize my own example, at an hour when I’m still awake.

Scenario #1: As per our world (sort of) GDP = 100, govt spending is 30% of GDP, paid for with taxes at 30% of GDP, tax rate is 30%, growth and the interest rate are real 3%, and as per Feldstein the deadweight loss cost of taxes is $0.76 per dollar of tax. Over three years…

[not knowing if the formatting will work]

Time: …T1 … T2 …. T3

GDP …100 …103 …106 … etc., forever

SPD…… 30 ….. 31….. 32

TAX…… 30 …. 31….. 32

Trt…….. 30% ..30% ..30%

DWL….. 23….. 23…… 24

Scenario #2: In T1 and T2 taxes are cut to $0 so former DWL is added to GDP … In T3 deferred taxes to cover all the spending are collected — they total the same 93 as in Scenario 1, but now require a 71% tax rate in T3 … This 71% is 2.37 times the 30% rate, squaring that is 5.6, times the original $0.76 cents DWL gives a new DWL of rate of $4.25 per dollar of tax … x 93 of tax = DWL of 395 … subtracted from potential GDP of 130 is not good.

GDP … 123 … 127 … 130 … end of sequence.

SDP …… 30 ….. 31 ….. 32

TAX ……. 0 ……. 0 ….. 93

Trt………. 0% …. 0% …71%

DWL …… 0 ……. 0 ….. 391

NET GDP in T3 …….. negative.

Yes this is an extreme stylized example, but you’ll see it does not support the hypothesis that collecting the same 93 of tax in different ways makes no difference.

The only way to avoid net-losing DWL in T3 is for persons to save dollar-for-dollar the exact amount of gov’t spending in years 1 and 2, instead of consuming any of it in spite of their “tax cut”, then pay it to the gov’t in T3 through a 100% lump sum tax.

Which, in effect, is the exact same as paying a 30% tax rate in T1 and T2 through an escrow account. In that case, where’s the tax cut and supposed deficit financing? (Talk about “Ricardian Equivalence”, we can see why Ricardo argued against it!)

Here in the US personal savings have hardly risen dollar-for-dollar to match our fast-rising mega-billion now trillion-dollar deficits. Not quite! We are solidly on the course of using large scale debt finance to defer taxes to “pile up” higher and higher in the future, by arithmetic, requiring higher tax rates to collect them, etc.

If this course isn’t changed the rest follows, as per exponential rise of the deadweight cost of taxes, as shown in the CBO’s economic projection and S&P’s projection of the US credit rating falling to “junk” by 2027, linked above.

And this is the what Mr. Sakowicz should have known to answer that question. Yes he should have known it. In fact, all talk show hosts should know it. If they did, we wouldn’t always have so many pundits pushing so called “tax cuts” with no matching spending cuts, that as a result are only tax deferrals, which just pile up future taxes yet higher, making everything worse.

When Deficits Become Dangerous by Michael J. Boskin in The Wall Street Journal on 12-Feb-2010 at page A23:

“Ken Rogoff of Harvard and Carmen Reinhart of Maryland have studied the impact of high levels of national debt on economic growth in the U.S. and around the world in the last two centuries. In a study presented last month at the annual meeting of the American Economic Association in Atlanta, they conclude that, so long as the gross debt-GDP ratio is relatively modest, 30%-90% of GDP, the negative growth impact of higher debt is likely to be modest as well.

“But as it gets to 90% of GDP, there is a dramatic slowing of economic growth by at least one percentage point a year. The likely causes are expectations of much higher taxes, uncertainty over resolution of the unsustainable deficits, and higher interest rates curtailing capital investment.

“The Obama budget takes the publicly held debt to 73% and the gross debt to 103% of GDP by 2015, over this precipice. The president’s economists peg long-run growth potential at 2.5% per year, implying per capita growth of 1.7%. A decline of one percentage point would cut this annual growth rate by over half. That’s eventually the difference between a strong economy that can project global power and a stagnant, ossified society.”